KEEP UP WITH OUR DAILY AND WEEKLY NEWSLETTERS

PRODUCT LIBRARY

a powerful symbol of the house’s cultural heritage, the jockey silk with colorful geometric motifs is an inspiration for leather goods and textiles.

connections: +670

watch our livestream talk with BMW Design at 19:15 CEST on monday 15 april, featuring alice rawsthorn and holger hampf in conversation.

connections: +320

the solo show features five collections, each inspired by a natural and often overlooked occurence, like pond dipping and cloud formations.

discover our guide to milan design week 2024, the week in the calendar where the design world converges on the italian city.

connections: 47

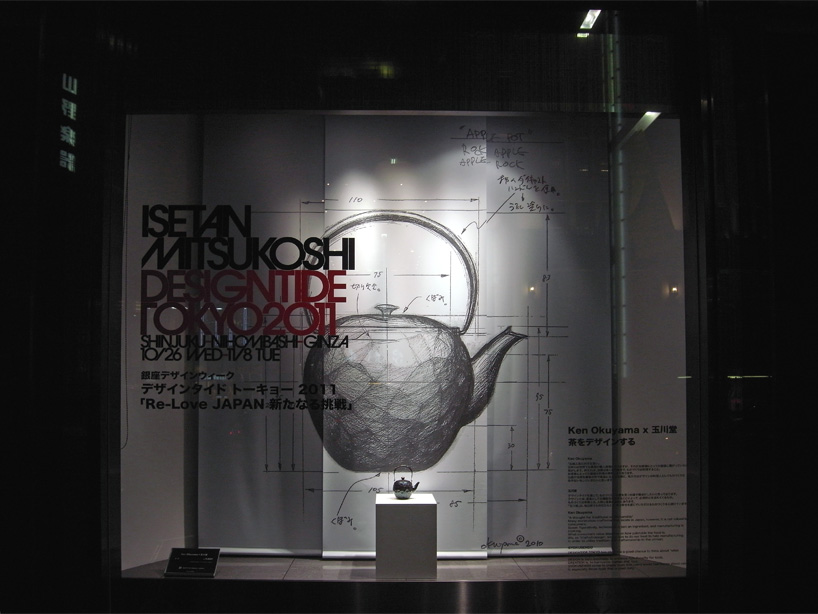

window installation at isetan mitsukoshi in ginza tokyo image © designboom

window installation at isetan mitsukoshi in ginza tokyo image © designboom ken okuyama at isetan mitsukoshi image © designboom

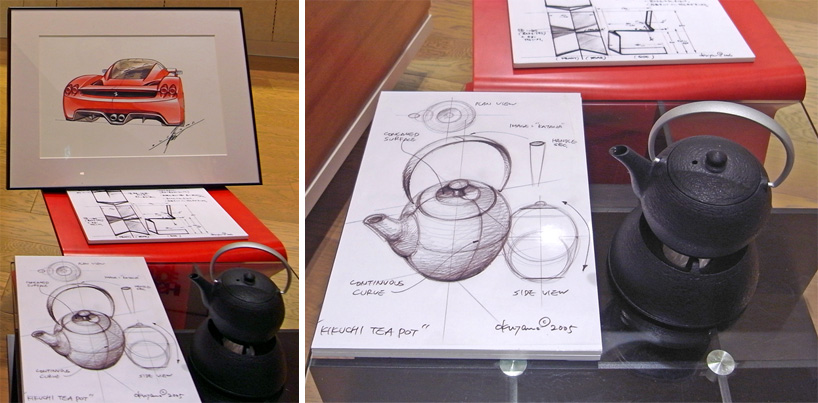

ken okuyama at isetan mitsukoshi image © designboom ken okuyama at isetan mitsukoshi : drawings of ferrari cars and teapots image © designboom

ken okuyama at isetan mitsukoshi : drawings of ferrari cars and teapots image © designboom ken okuyama and a few of his creations

ken okuyama and a few of his creations a teapot made of in a single sheet of copper image © designboom

a teapot made of in a single sheet of copper image © designboom techniques for coloring the metal are also unique to gyokusendo

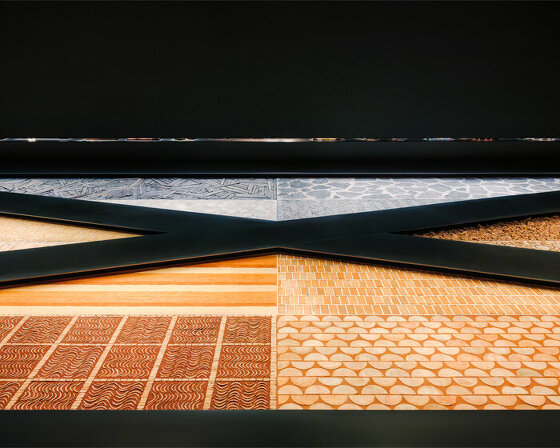

techniques for coloring the metal are also unique to gyokusendo a view of the exhibition that includes images of craftsmen at work image © designboom

a view of the exhibition that includes images of craftsmen at work image © designboom tools and steps of production, the company uses about two hundred different kinds of hammers(line below), and three hundred different kinds of toriguchi (upper line).

tools and steps of production, the company uses about two hundred different kinds of hammers(line below), and three hundred different kinds of toriguchi (upper line).

another view of the exhibition image © designboom

another view of the exhibition image © designboom various colour treatments on the surface of the copper teapots image © designboom

various colour treatments on the surface of the copper teapots image © designboom the company director poses to show how a craftsman sits at work

the company director poses to show how a craftsman sits at work