taschen publishes DIG IT!, a STUDY of earth-bound architecture

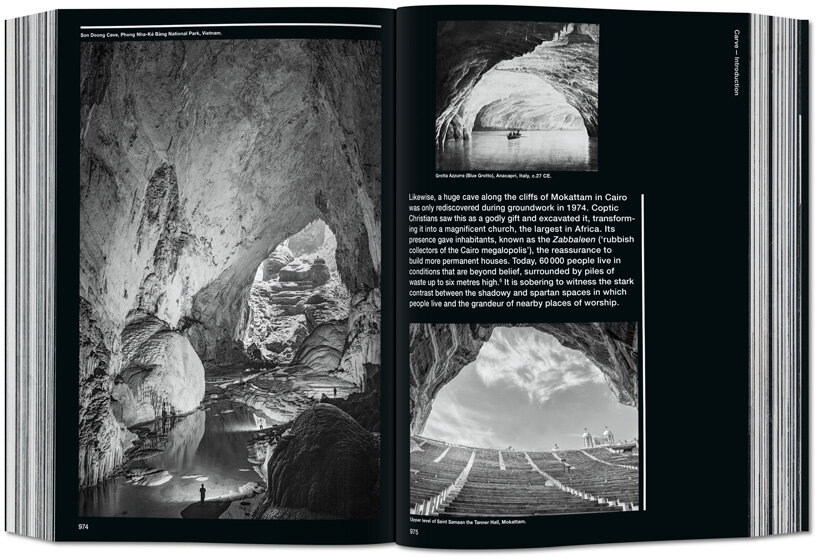

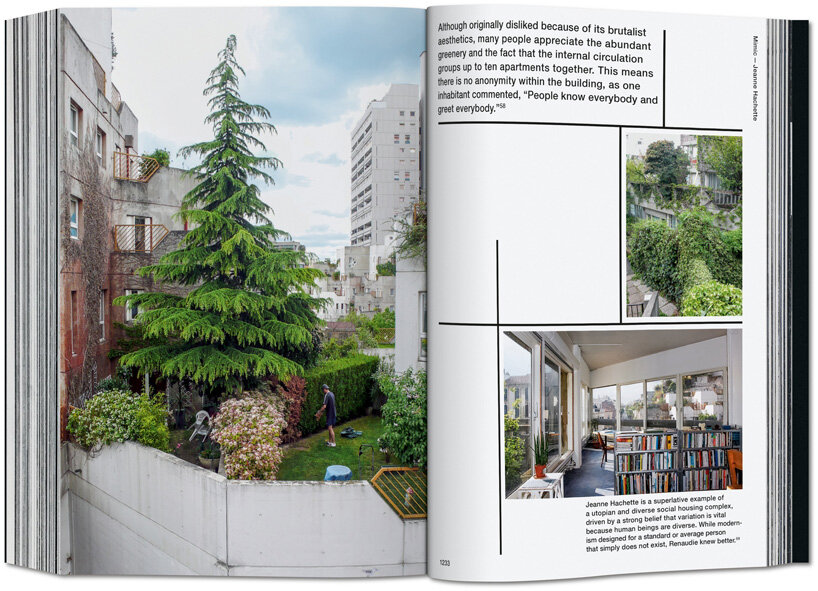

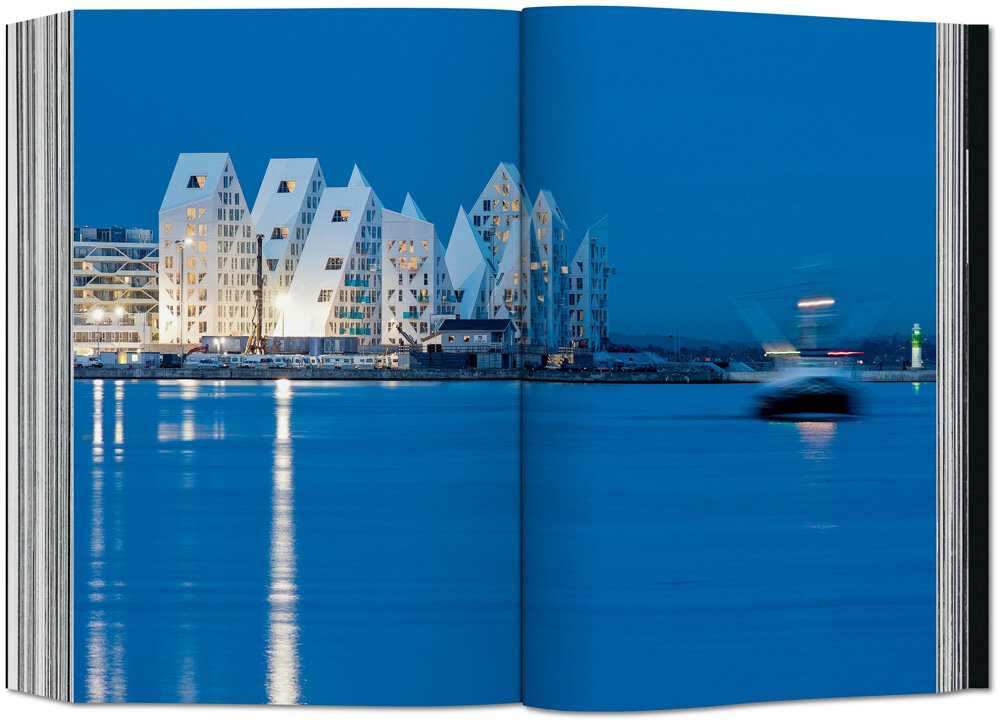

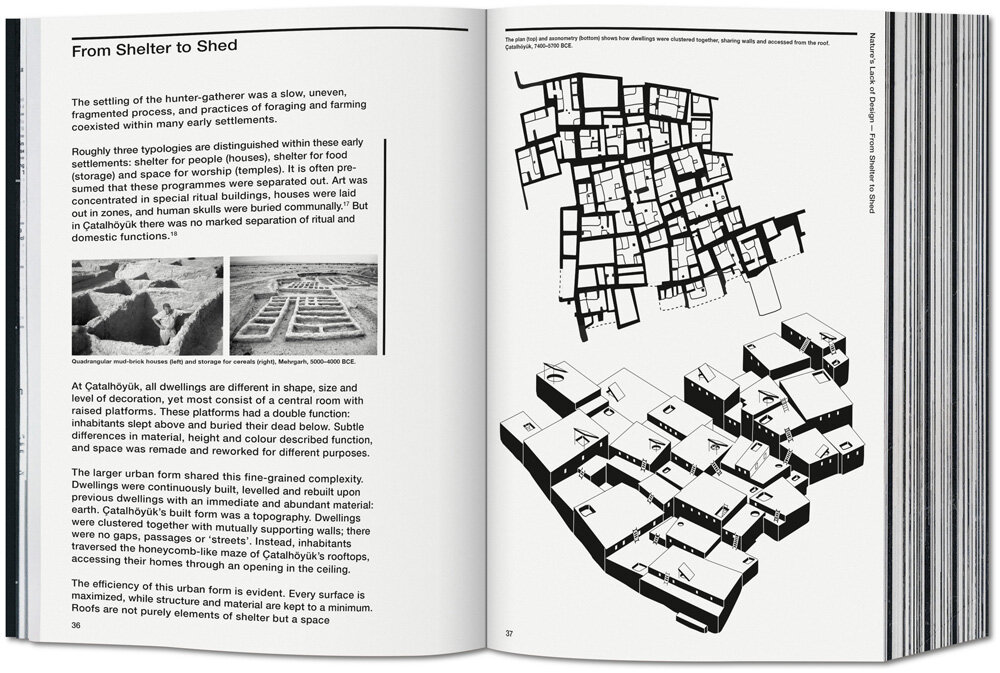

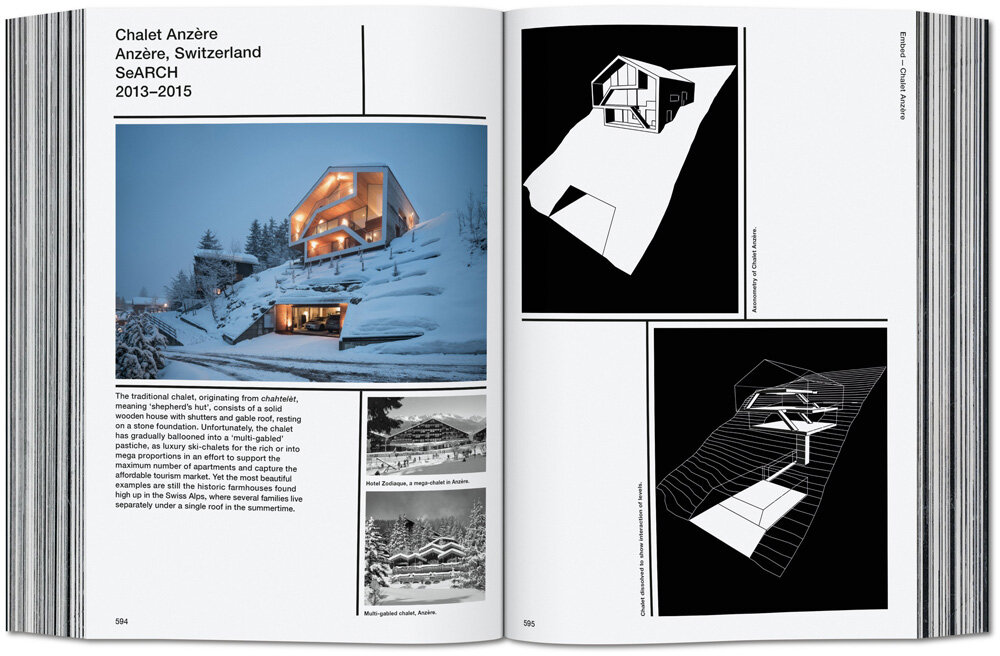

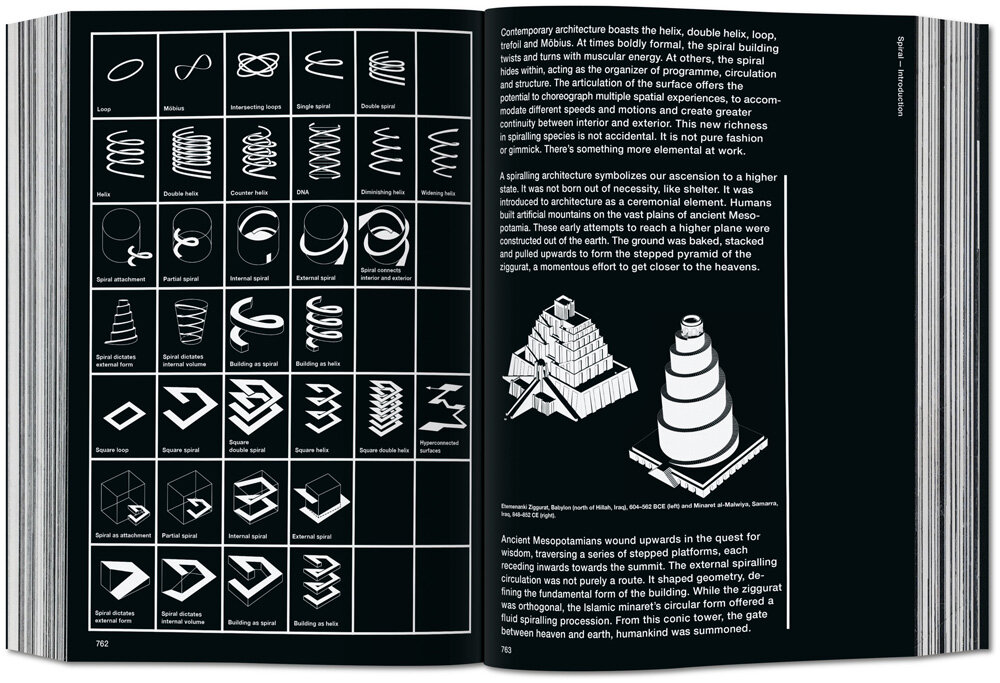

taschen explores architecture’s relationship with the earth with ‘dig it! building bound to the ground’, a new publication developed by dutch architect and founder of seARCH, bjarne mastenbroek, with images by architectural photographer iwan baan. in dig it!, mastenbroek and baan restore an understanding of the ground as a natural and sustainable resource through their study of earth-bound architecture from the past millennia. the book dissects over 500 case studies, from african churches chiselled in rock, to underground chinese housing, and vibrantly, overgrown parisian housing. its aim is to highlight the eco-conscious practices and green infrastructures that building with the ground nurtures – a necessary practice needed for the future of architecture, the environment and humankind. divided into six chapters —bury, embed, absorb, spiral, carve, mimic—this 1,400-page survey reveals humanity’s connection to the earth through building culture.

we spoke with bjarne mastenbroek to find out more about how ‘dig it!’ started, what strategies architects can implement to reconnect the crust of the earth with architecture, and what readers should take away from the book. read our interview in full below.

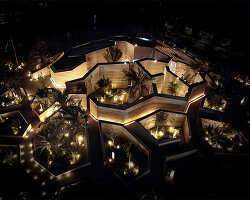

friendship centre, gaibandha, bangladesh, RBANA, 2011

friendship centre, gaibandha, bangladesh, RBANA, 2011

image © iwan baan

header image: stepwells, india © iwan baan

all courtesy of taschen

interview with architect bjarne mastenbroek

designboom (DB): when did you first start working on this research and what drew your interest to it?

bjarne mastenbroek (BM): it has quite a history. the very, very first one is, when I was quite young, I lived in a forest, a quite nice area of holland, spent a lot of time outside and built a lot of underground huts, huts in trees, etc. then I went to high school, and I started to study and during that time, until I left the east of holland, at 18 years old, the area where my parents lived, which was the forest area, became a neighborhood. and we were, my parents and I, we were all astonished at how people not only cleared the forest, they wanted to cut as many trees as possible – my family’s from norway, and they don’t do that, you just try to mitigate between nature and a house – the dutch, what they did, they cleared ir and then they started complaining about the deer and the rabbits, etc. eating their beautiful flowers in the garden, so they fenced it off. and that surprised us all. this sort of, setting yourself apart from that beautiful forest was for us, strange. then I studied, and during my studies, you were, let’s say, led into modernist architecture as a student at that time. especially after the brutalist period, it went back to, let’s say, hardcore modernism. at the end of my studies, I started to think, is this the way to do it? so I went to work for enric miralles, who was much more of an artist-architect, and an amazing man who taught me a lot about spatial qualities and about a different way of designing. then I started in a fairly big firm, I became partner in a big firm with a good friend of mine, dick van gameren, now the dean of the faculty of architecture in delft. we worked very hard, but I wanted to go away from the big firm to started my own, and that’s when I started working on villa vals. and that linked me back to this idea of underground building, this fascination that I had. I was like, I would like to build a house and then we had this steep slope, and I decided I was going to do it there. I’m gonna do this underground idea there.

kailasa temple, ellora, india, 756–773 ce. © iwan baan

(BM continues): then this idea came back to me, that we, as architects, or you can say, we as society are, quite often, sort of a party pooper when it comes to nature, natural qualities, even urban qualities, it seems we quite often kill the qualities that are already there. we just sort of trade them for building. and I thought it would be nicer if that could be more of a play-together. I didn’t want to romanticize it, or to make it in some kind of weird architecture that you cannot multiply or use in the city, or in general, to make a better world or to make a better connection with nature, make a greener city, a more relaxed city, better outdoor places. that all deals with this idea of building and landscape. and reading about it, I found out that there’s very little about landscape when it comes to building. there are books about landscape architecture, there are books about how landscape and building connect, but that is quite often talked about in a very different way. so I couldn’t find what I wanted to, a sort of search or research. in the first years while doing that and reading a lot, and trying to find a format for the book, it was very difficult. we found the format for the book with the six chapters and the introductory essay, only after five years. the book was finished two years ago, but then COVID came and it was a long way to really make it. so two years ago we finished, but only five years ago, we had the format. so three years before we finished, two and a half years. and that had to do with the idea of, if you read through history, if you sift through all these projects that came to us, beginning a lot with underground architecture, but later on more also synthetic, modernist, contemporary examples, I found out that we know in general, very little about architecture. so why do we do it this way? and why is architecture in fact, so clumsy? we drive cars now that are so amazingly high tech, whereas 200 years ago, we had horse and carriage. 200 years ago, we had a candlelight or a wood fire. or the way we did surgeries in hospitals, half the people died. newspapers were printed by typesetting letters in a box. nowadays, it’s all so incredibly high tech. if you look at architecture, it almost always links back to what we already did 200, 300, 400 years ago. so the progress in architecture is extremely slow. you could say it’s clumsy. I found out that my idea was, hey, architecture is outpaced by everything else. I have a house from 1620 and it surprises me, but also frustrates me, that that building is built better than what I can build now. so why is the building from 1600 better than what I do now? it’s not like with electricity, or cars or heating.. with building, it goes down, while all the rest goes up. so there is something wrong with building or the understanding of building. that to me was so surprising.

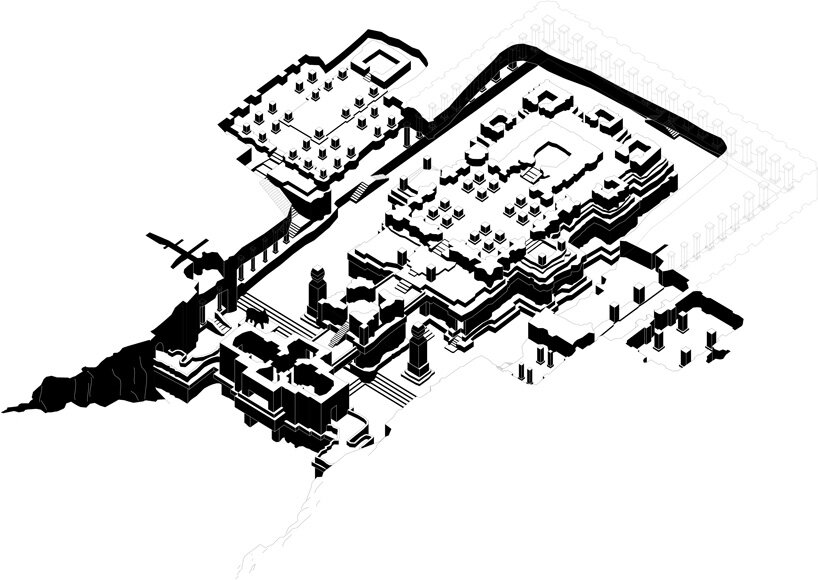

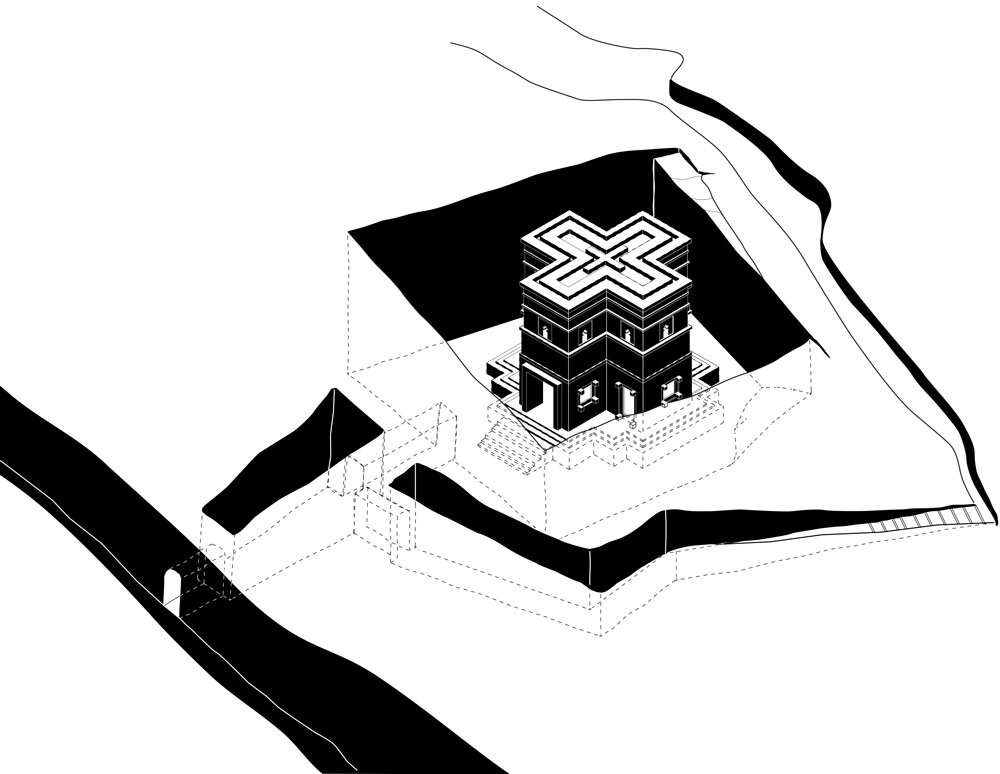

axonometry of kailasa temple, ellora, india, 756–773 CE.© SeARCH

(BM continues): then I found out that when it comes to how we treat nature, religion was extremely toxic. it put us as people above nature, and we subjugated nature, it is tradable, it’s exploitable, at god’s will. that’s how religion talked about nature. it has brought the world to the brink of collapse. and then science came in the last 500 years, and we had a lot of scientific developments. but with science, it was the same, it compromised as well. and science was always used for the benefit of us and not for nature, or whatever. so we acted the same way as what religion did, telling us that we were above nature. so with science, we killed it, with DDT, we killed it with nuclear power, antibiotics, chemicals..so it’s a domination. then finance came, you can say, in the post war era. it was finance that brought a lot of problems even way faster. religion took a few millennia. science took a few 100 years, but with finance it was in the last three generations after WWII, that it wiped out most of the qualities we have in natural life. and that’s through consumption. consumption has killed a lot of natural qualities, and I hate the idea that buildings have become a financial commodity. it’s also about trade. the essence of building is not the human need for protection, for living for eating, gathering, enjoying, relaxing, sleeping. buildings have become part of the greed, the deal, the opportunity..most people see money in a building, they don’t see space. and if you link that all, I thought the essence of architecture has been lost completely. and with the almost apocalyptic ideas of global warming, it seems we live in a very pessimistic time, at the brink of collapse, or sort of, we have to be very careful otherwise everything is going down. you could say that after religion, science, and finance, the idea of the protection of the environment has been treated as a killjoy for the last 30 to 40 years. even greta thunberg nowadays is ridiculed. so something goes wrong there. and the environmental revolution could be our only way out now. I think that’s completely clear. and therefore we need to understand better what we can do with buildings. I think buildings could have a healing quality, they have to have a healing quality in the future. we have to heal the wounds. so how can we realize those two things? how can we do it way better now? and why don’t we understand at all, what the crust of the earth, landscape, and architecture can do together?

the minaret al-malwiya, part of the great mosque of samarra, iraq © iwan baan

DB: so what strategies can architects implement to reconnect the crust of the earth, or the landscape, with architecture?

BM: we came up with this timeline after a couple of years of research, this format where we thought, hey, it could be nice to make a format where we sort of detach ourselves from the earth more and more. so we start underground, buried, and then went on with the other strategies, from being completely underground, to being embedded in a hillside, then being on top of nature, then spiralling up and down, then carving out, like a grotto almost of big volumes where we can implement nature inside our buildings. so we invite nature inside instead of bury ourselves underneath. and then the very last moment is, let’s say, mimicking. in densely populated cities it is a quite interesting thing, and that’s what you see nowadays, that buildings become more and more influenced by natural phenomena. so that a building is like a tree, or a building is like a mountain, or it’s floating. so where you mimic nature within your building. and that is, let’s say, from going completely underground to almost floating in the air. and history also tells that either people dug holes, or they protected themselves in grottoes until they started climbing on trees and building little huts. so either going up or down. it was really beautiful to find out that those strategies – bury, embed ,absorb, spiral, carve and mimic – illustrate this timeline in a certain way. we liked it very, very much.

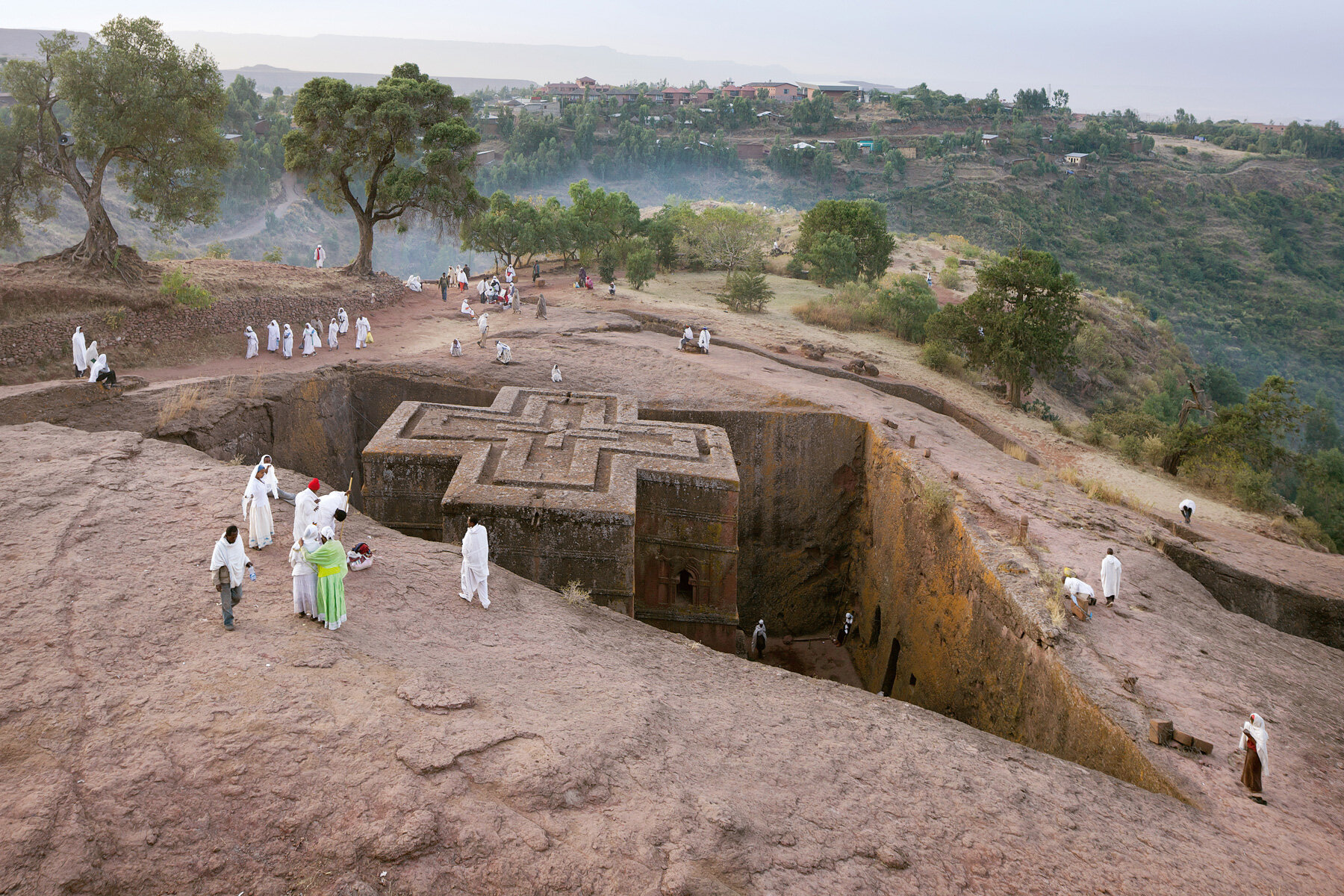

biete ghiorgis, lalibela, ethiopia, 1100–1200 © iwan baan

BM: for a big part, it’s the buildings that have fascinated me most on my trips around the world. so a lot of these buildings I had seen, some of them 20-30 years ago, some more recently. so very intuitively, I picked the buildings that were in the back of my head since then, because they were so good, so beautiful, so impressive. and then I wanted to use the best historical examples that I also had not visited. I’ve never been at the stepwells unfortunately, but I was extremely fascinated, I knew about them. I was extremely fascinated by yaodongs, the underground chinese houses where 40 million people lived. so those two I haven’t visited, but I wanted to implement them. also, a few others like lalibela in ethiopia, where I have been.

(BM continues): then I knew about a few contemporary examples from colleague architects that I thought could really show us the examples now. so like, the roof gardens of le corbousier, which were always seen as sort of a failure, or the elevated street of moshe safdie, which for 20-40 years was not so successful, but now in the revival, they became successful, they’re hot. and then you have contemporary examples that look like safdie, but I think safdie is the best, there is not a building yet built in the last 20 years that is better, it will never get any better than safdie. so there you see again, that architecture goes backwards. there’s an amazing example, and then it’s never like it again. I think you cannot make a moshe safdie building anymore. it’s too expensive, it’s impossible. it’s the same that ada louise huxtable, the famous critic from the new york times, once wrote about penn station, this amazing big railway station in new york that was deteriorating and looked like shit in the 70s. she wrote, how come that we have built this amazing castle, which, at the moment, we are absolutely not able to build any more. what we once did in architecture is impossible now, whereas with everything else we do in the world there is progress. for example, when there is a new level of quality of car, it will never be lowered again. I mean, every other car strives to be even more high tech, but in architecture not.

villa vals, vals, switzerland, SeARCH & CMA, 2005–2009 © iwan baan

DB: why do you think there is this big difference between industries?

BM: you could say religion, finance, you could blame them for killing this world in an accelerating speed. what’s happening is terrible, we have to stop it. but architecture is so slow, it is so backwards, it lacks progress. and therefore it’s so pathetically naive, that you can’t almost blame architecture for all these things. architecture is almost innocent. we’re not able to do with architecture what we can do with cars etc.. but architecture could have a healing element where we rebuild our globe. we are living in the anthropocene, so you could say everything is built on earth. and architecture is the only one that is stuck to the crust of the earth. it becomes part of earth. whereas a car can never heal. it could be neutral, do no damage, but it cannot heal. you could say a windmill can help us a lot, but even so you just come to a neutral situation. but if we start rebuilding mountains, rebuilding marshes, rebuilding landscapes, rebuilding forests, with necessity, with architecture… you can plant trees on buildings, you can invite nature in. nowadays we invite animals in our buildings, you can build for bats, bees, birds etc. so we can heal with architecture, it could be a solution for part of our problem. and in a way, there is no other option because we have to do it. so I think architecture is completely different from any other act of humans because we screw it to the earth, literally. with mining we take out, so there are those two actions: either we dig out, we mine gas oil – and we should stop that – we mine sand or water or diamonds – we should be careful with that too – but we also build. and those two actions are connected to the globe. all the rest is detached, you could say. and therefore I think it is very special. what you see also is that in architecture people think in terms of nostalgia, they think in times gone by, they look back. with a car they never look back, with fashion, they don’t look back so much. of course you’ve got retro styles, or music, but there’s always the new thing. in architecture, it seems people like the old thing. it must be about security, but also be about a deep emotion. there’s a much deeper emotion.

zeitz MOCAA, cape town, south, africa, heatherwick studio, 2014–2017 © iwan baan

DB: it may also be because the longer a building exists on earth, it proves its timelessness, its worth.

BM: yeah, we do value such buildings, and they become part of our identity. you could say that we are what we have built. the parisian is a parisian because of his/her buildings, a roman, a carioca from rio, or if you’re from moscow, or amsterdam. for a big part, your identity comes from what has been built there in the last, let’s say 1000 years.

costa brava clube © iwan baan

DB: what do you hope readers will take away from ‘dig it!’?

BM: I hope very much that people see that it’s not very difficult to do it. so the banality of architecture now, let’s say the bland stacking of floors of high rises, the detached, satellite cities still being built, what you see happening in africa now, is a disaster. china builds four or five story concrete buildings everywhere now. I think the book shows that there is a way more diverse and intelligent way of building. so that it helps people to believe yeah, we can do it. and, as I said, we must do it better, we must do it way, way better. because we need to heal the earth in a way. and so everybody should work on that. in architecture, we can also make a CO2 negative buildings by storing a lot of carbon in wood structures, for example. it won’t solve the full problem, but it can help a bit. and every part of the world, every profession, every human action should at least help a bit to solve the big problem.

DB: have you worked on any projects that implement these principles yourself? are they included in the book?

BM: I’ve put about 20 projects by myself in the book. we had the presentation last night in hotel jakarta, which is an amazing place, completely prefabricated, wooden hotel units, with a wooden main structure, wooden roof, and then completely clad into PV panels. I’m very happy with that building and we do a lot of wood structures now. and then, next to that we did quite a few underground houses, or semi-underground or embedded buildings in ethiopia, villa vals, and novo nordisk, the conference center in denmark, which is also in a hillside. we do a lot in that, and that’s also why the book starts from that idea of, hey, we should do more about this. it’s easier than you think, we should just do it. that’s so important, and it’s also what I want to show in the book. just do it.

musée gallo-romain, yon, france, bernard zehrfuss, 1966–1975 © iwan baan

cover

cover

bjarne mastenbroek. dig it! building bound to the ground

hardcover with fold-out, 19.3 x 27.1 cm, 2.58 kg, 1390 pages

project info:

name: dig it! building bound to the ground

editor and author: bjarne mastenbroek | seARCH

photographer: iwan baan

publisher: taschen

architecture interviews (267)

designboom book reports (197)

earth architecture (59)

iwan baan (102)

seARCH (8)

taschen (14)

PRODUCT LIBRARY

a diverse digital database that acts as a valuable guide in gaining insight and information about a product directly from the manufacturer, and serves as a rich reference point in developing a project or scheme.