k-studio is a creative practice based in central athens, working across different scales, from private holiday homes to restaurants, bars, hotels and resorts. founded by architects dimitris and konstantinos karampatakis, the greek studio develops holistic experiences informed by tradition and the local context, and enriched by contemporary aspirations. over the years, their practice has evolved to specialize in the design and realization of projects within the leisure industry, including the recently-completed ‘kalesma hotel’ in mykonos, and ‘dexamenes’, a coastal hotel occupying the site of an abandoned wine factory in the peloponnese.

designboom visited k-studio’s office in lycabettus hill, and spoke with dimitris karampatakis to find out more about their background, creative process and upcoming projects. read our interview in full and explore images of the firm’s studio space and key projects below. k-studio founders, dimitris(left) and konstantinos(right) karampatakis

k-studio founders, dimitris(left) and konstantinos(right) karampatakis

image by peter landers

designboom (DB): how did you go into architecture? how did you start your practice?

dimitris karampatakis (DK): our father, konstantinos and mine, is an architect and he brainwashed us, we had no choice. he would take us to construction sites, we would visit his office, and from quite early on we developed an interest in the process of making. it wasn’t so much about designing itself, or, more specifically about buildings, but it was just an interest in the process of making stuff. so quite early on konstantinos and I would get involved in constructing things that were not very useful, I would say. we would start quite small, but it would become ambitious quite quickly and take over the whole room or even outside, digging, and pouring concrete and casting in the garden. as we became more body-abled, these things grew. so our interest in the process of making gave us a direction towards seeing how we could explore that in our studies. when we were contemplating about studying, I think we both felt that architecture was the right first step; understanding why and what and how to construct. from the different universities that we looked into the bartlett was a university with a lot of focus in making, it has a workshop – an extensive one – and over the years it has grown. when we visited it, we got really excited with all the different machines and different techniques, and it definitely attracted us because of that. through our studies, we tried to find more about what to build and why to build rather than understanding the process of building, but we understood that it was a necessary step.

k-studio’s office in lycabettus hill, athens | image by peter landers

DB: the bartlett is known for its experimental approach to materials and functions. do you apply any elements of that experimental approach to your projects now, and how?

DK: the good thing about the bartlett is that it doesn’t give you a sense of style, although there’s an intro in every university to ensure that there is definitely a standard definitive style. the bartlett taught us how to analyze things, and to design according to a brief and a location. so in a way, respond to give an input, not to have an aesthetical or materialistic kind of goal before you start. so it was more like a building could be anything, it could be made out of anything, it could be nothing as well; there was no pressure of an architectural, at least, style. if anything, it was rewarded when things did not look as they would be expected to look. as architecture students we really explored and emphasised the process of learning how to think in a contextual way. so, going to a certain site, understanding it, well, not just the specific site, but the greater site, the heritage, the culture, the materials that it offers because of its location, and because of its heritage, and then to approach it in an open minded way of what these materials and what these techniques could do. so again, not to predetermine something. that helped us a lot, because as a studio, we work in different places. we work from the cycladic islands, which have a very strong heritage, to kuala lumpur, which is a very different place. so it allowed us, as a studio, not to have an aesthetic kind of goal and outpost where when we start a project, we would kind of just slowly move towards a predetermined goal, but to explore. of course, on the way, you create things and they influence you in ways and we also get preferences, but we remain very open minded every time we start a project. then, the second layer is the process of making: we get really excited about balancing between keeping the materials in their raw form, and almost showcasing that beauty, and at the same time showing how craftsmanship, how working with the material, can do other things. we’re always trying to balance between those two, and I think that gives us a continuity in our projects, but not necessarily in a stylistic way, more in the method.

image by peter landers

DB: how do you apply craftsmanship in your projects? do you still experiment with materials here, or do you work with craftsmen that are local to each project?

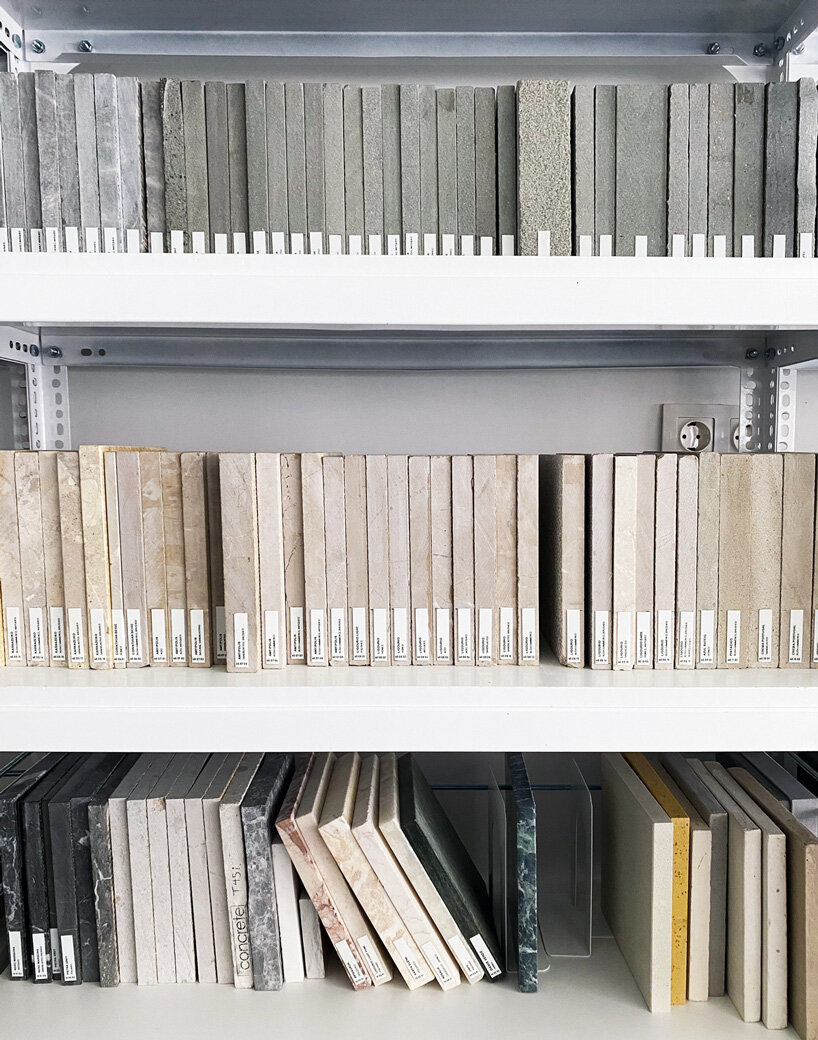

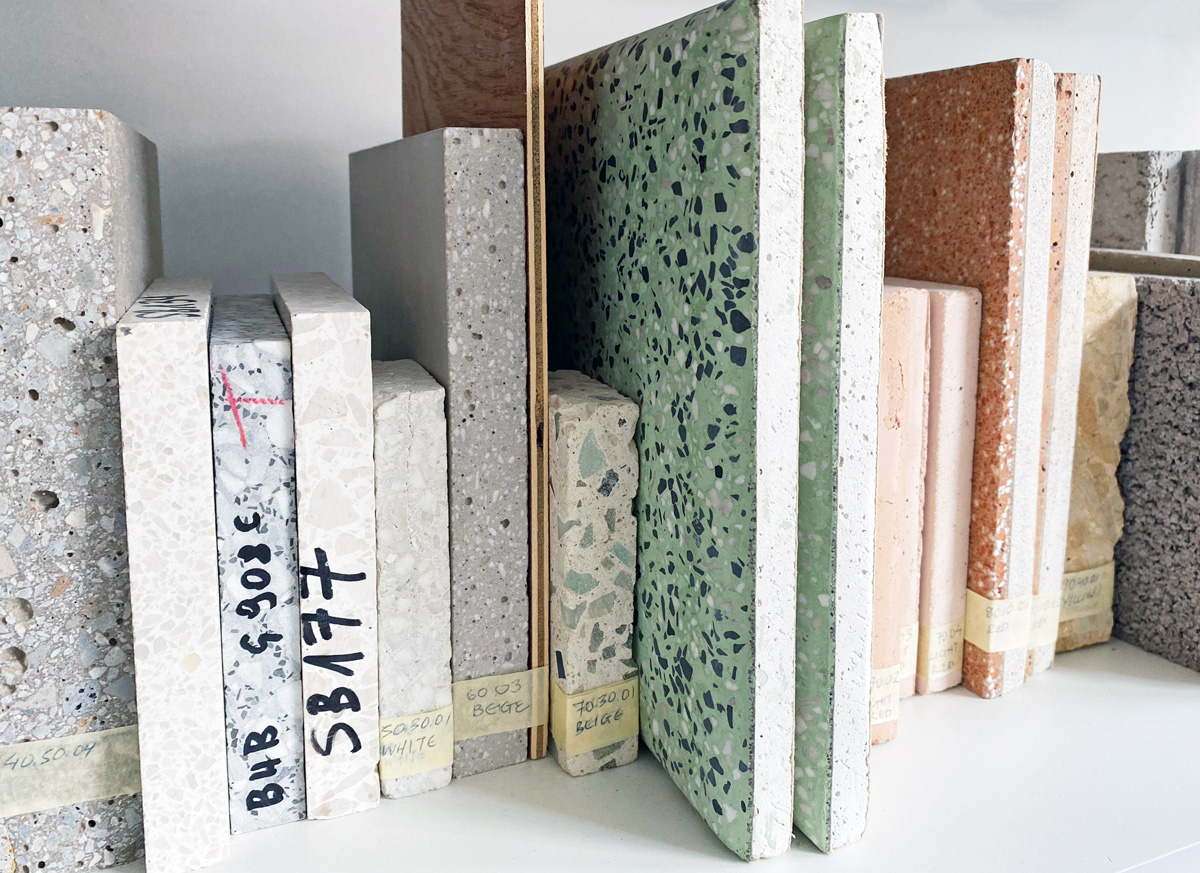

DK: we do both. so we’ve got quite an extensive samples library and over the years we have made good connections with different experts in stone, wood, metal, glass, aluminum, and recycled plastics. whenever we find someone as geeky as we are, we just established a strong bond and then that grows. so we do a lot of experiments during the design process, which are ongoing, and then for each project, of course, we try to learn and incorporate things that we find there. and that of course requires that we find someone who is local, who understands material technique heritage from a specific location. so we grow that network in different countries, and that’s even more exciting, because you might see things that you haven’t even thought of. so you start talking about working with materials that will inform you on how you deal with things when you come back home as well – it’s quite a nice experience.

material library (detail) at the studio | image © designboom

DB: do you have some examples of that?

DK: we worked a lot in the cycladic islands and when we first started as young architects of course, we wanted things to be a bit more dynamic in aesthetics or in geometry, and the cycladic islands have a very strong heritage of white lime washed volumes. when we first did a project in mykonos, which was called ‘alemagou’ – it’s a beach club in the north part of mykonos – we were trying to find other elements of the local architecture that we could use so that we could move away from that white volume, which is beautiful, but we wanted to respond more to the natural beauty of the beach. this is a beach club, so we felt that the white volume would connect it more to an urban kind of town, rather than the beauty of the natural stone. so we turned to the ‘pezoules’, the dry stone walls which are everywhere, and we thought that this became more appropriate as a building technique. so we made these walls, like a little ‘avli’, which is like a courtyard, and then used the limewash just to bring in focus, almost create a punctuation within the structure, just painting it quite freely in different places.

‘alemagou’ in mykonos | image by yiorgos kordakis

DK (continued): for the pergola, we researched what we could do, something that would respond to local architecture, and found that in the cycladic islands they would use leaves and grasses mixed with mud to create a 60-centimeter insulation layer. so they would put these wooden beams, then they would put a ‘petsoma’ (wooden planks), and then on top of that, they would pile it about 60 centimeters with mud and grass, and then screed on top in order to put the water insulation. we got excited about the idea of maybe using that grass in a different way, so we turned it upside down, we made a pergola out of the wooden beams that you would have in an internal space in the same rhythm and the same technique. instead of piling the grass on top, we kind of let it hang, and by letting it hang, an interesting thing would be that apart from the historical reference and the cultural reference, it also allowed the heat that usually accumulates underneath a pergola to escape. because, of course, as it was hanging, it was permeable, it didn’t have anything to stop the heat from just leaving the top. and it also brought a very beautiful, dimmed sunlight, so it didn’t block the element totally, it provided enough shade, but it also allowed this quite beautiful choreography of light. at the same time, it took advantage of the strong winds– mykonos is very windy. we thought that we wanted to do something with the wind because the environment there is so dynamic, you look at the sea, it’s moving, you feel the wind on your face, and we wanted somehow the building to also respond to that. and again, just in a way, we hit two birds with one stone, the grass, of course, being hung, and not tightly, it allowed for movement, it basically is moving around from the wind. that brought a lot of movement to the building, it brought a beautiful soundtrack to the building, and it also made the sun kind of respond almost in the rhythm of the sea. this is something that was just about keeping an open mind with an old fashioned technique and kind of playing around with it. we spent a lot of time hanging grasses at different distances and at different lengths and experimenting with about five different grasses and then moving onto other grasses, another five and another five and finding utility because of course you’re eating underneath and what happens when all these things fall into your soup and your salad. and then we thought you know, you’re at the beach, it doesn’t matter if something falls in your salad, so there were a lot of practical questions and a lot of real issues that we had to go through. what I’m happy to say is that, you know, keeping an open mind from the beginning until the end, and not just us, but also our clients, we managed to do something which is very connected to local culture and heritage, but at the same time, it is new, it is exciting, and it fits well where it belongs.

‘alemagou’ in mykonos | image by yiorgos kordakis

DB: here you’re incorporating elements that are part of the local landscape, and I’ve noticed that in some other projects of yours, where you’re incorporating existing elements, from rocks to existing derelict constructions. how do you know what to keep and what to throw away?

DK: it’s an ongoing debate, especially living in an ancient country like greece. there’s a constant debate of what is important, what do you keep, is it important because it’s 1,000 years old, even if it was just a kiosk? and what does a modern kiosk have that the old kiosk didn’t? there was an interesting proposal by rem koolhaas of OMA, quite a few years ago, in a chinese city. they said, what are we going to keep? is it heritage buildings? is it cultural? is it the religious buildings? and OMA suggested that they would make the whole city into a grid, of, I think, 500 meters by 500 meters, and then just decide, this you keep, that you don’t keep. and just by that you give equal importance to today’s kiosk and an old temple. and then the next one, you know, you just demolish everything, and you make everything new. and then you create this palimpsest, this quite interesting interplay between now and then. I thought that, of course, practically, this is very difficult to do, but it gave a good answer. it’s almost by random, because things that were kept for 1,000 years, it’s probably a random process that allowed them to exist until now. I think that, as architects, we are asked that question just silently, by the side. you go to a beautiful site, and you’re asked, do you keep this tree? do you keep this beach? or do you place a marina, you know, and this conversation is always complex. or you go to an existing building, it might be beautiful or not, conventionally beautiful, or unconventionally, and who are you to decide if to keep it or not. a lot of these processes are exploratory, what is the value of keeping something on, it becomes almost like a commodity. although that is making it a bit dry, and a bit too pragmatic, it’s probably the realistic way that an 1,000 year old something or other was kept, rather than something else. it was out of pragmatism of the time, and then of the next time, one of the next time, and by almost approaching it like that you’re just, in a darwinian kind of way, giving it a next lease of life or not. for us, when we approach a project that is located in a beautiful natural place, I think nature always takes a green card, you’ve got to keep that, you cannot make anything better than that. therefore, you should be humble and just decide to keep as much as possible. when it comes to the built environment, I think, again, humility is important, but at the same time, it is more about a commodity.

‘dexamenes’ | image by claus brechenmacher & reiner baumann photography

DK (continued): ‘dexamenes’, for example, is a project where we had to answer that. we were approached by nikos karaflos, who had bought this old winery, an ancient old winery, right on a beautiful beach on this stretch of this idyllic sandy beach in the western peloponnese. his dad wanted to demolish it and nikos didn’t, so we were approached to give an answer on that question. we went down to the site, we walked around the industrial building and the place was left for over half a century just to the elements, exposed to the salty air and all the weather conditions. everything looked out of scale because it was built for an industrial purpose, to process raisins and wine on a bulk level. so one thing was that the beauty in the contrast between such a beautiful idyllic beach, and this industrial building was quite unique, and that was something that we felt, could bring a uniqueness to the project ahead. at the same time, the materials had taken on a beautiful patina, a patina, which some might say it’s not beautiful or it is beautiful, but we felt that it is again unique. I mean, to get this kind of finish, it takes more than 100 years, so it was almost like, you cannot recreate that. this uniqueness, again brought a value to the project ahead. I’m sure another developer will see the same opportunity that nikos and his dad saw, but no one else on that stretch has a building, which has taken 100 years to build. so we saw that as an opportunity, and we saw the beauty in that as architects, but we also saw the value in that as business consultants. architects should not shy away from becoming business consultants. I think architects traditionally were the first person one would consult on an investment, from what land to buy, or where to build this or that, and over the years with design and built contracts, kind of shifting as the norm, architects are coming, as far as I’m concerned, too late on a project, when a lot of these difficult, important questions have been answered. and then it becomes more about almost an identity exercise or an architectural process of composition.

‘scorpios’ in mykonos | image by steve herud

DB: this project is really unique. do you sometimes get clients who say ‘I want exactly what you did there’?

DK: we’ve got a lot of people coming and saying I want a ‘scorpios’, or you know, this or that or the other, which is flattering and it’s rewarding in someone recognising the success of a project. we value that a lot, but at the same time, k-studio has a promise of trying to have a unique response to each project. but for example if you go to santorini, and there you’re on the cliff looking at the volcano, and someone is asking you to make a hotel right there, and then another person is suggesting another hotel right there, obviously, when the starting point is so similar, the reaction will be close. but even then, we try to focus on the differences rather than the similarities because we feel that as architects, of course, we design buildings, but we also design identities, and this is part of the offering. these identities are commodities in their own right, especially in a commercial development, because as a hotel or a restaurant, what they’re offering is, of course, a bed and food and service, but they’re obviously offering a place and an identity with it. so we’re quite conscious that if we sell an identity to one client, and then we go and resell it, it’s almost like shortchanging the first client. we try to respond as honestly as possible to the project ahead, and that means that sometimes there are similarities because we wouldn’t want to, just for the sake of difference, go and make something that just doesn’t fit, but at the same time we do try and make it as a different response.

‘scorpios’ in mykonos | image by steve herud

DK: we have recently completed a hotel in mykonos called ‘kalesma’ in collaboration with studio bonarchi, which is in a little mykonian village on top of a hill in aleomandra. we’ve completed a restaurant in mykonos called ‘noema’, which is for the scorpios group and it is in the town in an old courtyard, an old open cinema. it’s a big opening in the middle of the town, which is really, really beautiful. suddenly, you’re in a garden. we’re working on a development in asteria glyfadas, which was built back in the 50s as part of the national tourism organisation (EOT) and the national bank of greece as part of a, then, rebranding of greece in a new light. the national bank of greece and the national tourism organisation of greece got all the then young architects, who, back in the 50s were all modernists, and they made these quite ambitious projects around the coast, the athenian riviera, what is referred to, from the asteras palace to asteria, to other things, and of course, the xenia hotels throughout greece. we’re working in collaboration with a6a and audo architects on the asteria glyfadas, which is a very interesting project. it’s going to be finished next year.

‘villa mandra’ in mykonos | image by claus brechenmacher & reiner baumann photography

DK (continued): we’re working in kuala lumpur on an apartment tower, which is very interesting for us. it’s the first time that we tackle this kind of topology, which is quite intriguing as a location, but also as a typology. then we’re doing 100 branded apartments in tenerife and a clubhouse, like a deconstructed hotel, with our local partner there, omar arquitectos. we’re working in qatar, we’re doing a large scale residence in doha for a private client, we’re working in israel, for another private residence. again, very different cultures, very different places, very interesting process of learning and connecting. we’re working in thailand doing a beach club. it’s something that, again, is very different to the cycladic islands, beautiful nature, amazing craftsmanship and amazing materials. we are working in panama on a private island, doing a resort, which is, again, a little ecosystem in its own right. our first response was ‘yeah, we’ll make beautiful wooden structures’, only to find that there’s termites that would eat everything made out of wood, so that was not an option. it was very interesting how a little insect like that would just make a design decision. we wanted a low impact on the island, so we went with prefabricated metal frames cladded with grass and other elements that we would find on the island without chopping down trees; taking the things that would dry out anyway. so pruning trees, rather than cutting them down, and working a lot with prefabricated interiors as well. trying to minimise work on the island as much as possible.

‘villa mandra’ | image by claus brechenmacher & reiner baumann photography

DK: we have grown as a team, we are 66 architects and interior designers here in the studio. well, actually, for a year now we’re working remotely, but we’ve got a small team here of 15 people, and everyone else is in their houses or in whatever cool place they’ve managed to weather out the pandemic. we also have a good network of collaborators beyond our team, who we work with on the projects I mentioned. on noema we are working with lambs and lions, who we’ve worked with in different projects, we work with audo and a6a as I said in ‘asteria glyfadas’, with leonardo omar arquitectos in tenerife. we work with WATG on different projects; we worked together on a project in turkey and a project in crete. at the same time, we enjoy having different things happening at once because they kind of cross reference, cross breed, there’s a cross pollination of projects, and that becomes quite an inspiring process. in our structure, we have our six creative directors, who coach parts of our team: marivenia chiotopoulou, giorgos mitrogiorgis, christos spetseris, marianna stavridou-kouvara, michalis skitsas, alexis chortogiannis and dimitra konstantinidis.

‘vora’ in santorini | image by mirto iatropoulou

DB: have you noticed any shifts since the pandemic, either in the projects you work on or in the way you work at the studio?

DK: I think everyone’s hope is that the pandemic is going to just come and pass, and that we don’t need to redesign everything. but for sure, what it will do is help us understand that we don’t need to go every day to a building to work. I’m not as knowledgeable on other things, but from my personal experience, which I can vouch for, I’m definitely going to be thinking now how we can run our practice with the tools that we’ve incorporated over the last year. we work remotely through google hangouts and meet, and we have a jamboard where everyone’s working, and this has proven very efficient. usually in a meeting, you’ve got ten people and everyone’s trying to get a pen and draw something, whereas now, you’ve got ten people that can be from all over the world, all these different experts at the same time, having a plan in front of them, where they’ve got their allocated color, and they can say, ‘what about this? what about that?’, and that is unbelievable. I can’t imagine moving forward with losing that. at the same time, I think our team has benefited a lot from being closer to their families, maybe even deciding that for part of the year they might work from a different place, just because it suits their daily rhythm. I hope this is something that we don’t lose, but we actually work towards. that has potentially an impact on the built environment, at least in an office typology.

‘vora’ in santorini | image by stale eriksen

DK(continued): we are renovating our office, and the reason we’re doing that is because we’re trying to find better ways to play in the office rather than work. we have grown over the pandemic, this time last year we were about 55 people, now we’re 66. we grew to a team that now doesn’t fit our studio. what we have missed is each other, and interacting not during work, because during work, we’re doing it, but we’re missing the jokes that are said in the corridor, and having lunch all together. we also do kickboxing every tuesday and yoga on thursdays, and on friday, we do an internal presentation and get drinks after. we’ve been doing these things digitally, but it’s not the same interaction. so, I think that offices should be thinking on how to bring teams together not to work, but to interact, to build bonds, to develop R&D ideas and talk about the future and about each other rather than the everyday kind of work. I think that happens quite efficiently from a workstation, connecting through a digital platform, and buildings can become these incubators that bring things closer rather than places necessarily just to work. of course, this doesn’t work for all professionals, I am on our little microcosm, and during this pandemic, I think everyone has zoomed in. hopefully we can start zooming out again and connect with other things that don’t involve our daily routine. I do understand that this is a very specific comment for a very specific part of what an office does and needs, but talking with other designers and people in the industry, we all felt that we want to go back to the studio to have some drinks and talk and play. giorgos mitrogiorgis is amazing at scrunch paper basketball, he’s got the record, I think, for the longest shot. we haven’t done that for a whole year, so he’s the reigning champion for a whole year but that’s not fair. because you know, they are not here, so I cannot do it and I want to claim that back!

the k-studio team | image by peter landers

DK(continued): more than that, I think we are appreciating the outdoors more. this is something that as greeks we understand quite well, because of the weather that we enjoy here, we embrace the outdoors. it’s quite funny when we design a restaurant or a hotel, we usually give more importance to the outdoor areas rather than the indoors, because it’s not very often that someone goes to a beach location, and they want to have dinner inside. they all want to be right at the beach. even in london, I remember very clearly that the minute there is a little bit of sunshine, everyone’s out at the pub, and they’re drinking out. I’ve got no official statistics on what I’m going to say, but I think there are more convertible cars in london than in athens, percentage-wise, and that is because the minute it is not raining, they’re opening that car. I really, strongly believe that spending more time outdoors, whether it is hiking or at the park or by the beach, or just outside the pub, is something that will hopefully stay with us and will make us more connected to our cities and our environment, and we will require less built environment as well. we’ll build hopefully less, because you don’t need everything to be done by a building, you know, you can have a building, and then you can have a pergola, you can have a courtyard, you can just have a garden. hopefully that’s gonna allow us to shift that mindset from expensive buildings to build and maintain and run, to things that are a bit more unfolded, maybe things that always have an outdoors to support the indoors. hopefully that is here to stay.

architecture in greece (251)

architecture interviews (267)

k-studio (9)

studio visits (112)

PRODUCT LIBRARY

a diverse digital database that acts as a valuable guide in gaining insight and information about a product directly from the manufacturer, and serves as a rich reference point in developing a project or scheme.