open architecture and designboom

Following the publication of their new book, OPEN Architecture founders Li Hu and Huang Wenjing travel to New York to lecture at the Center of Architecture. Titled ‘Reinventing Cultural Architecture: A Radical Vision By OPEN,’ the work outlines six of their recent cultural projects in China — five completed, one under construction — and marked a thorough outline for the exploration of their design philosophies. Expressing sinuous curves and rugged surfaces, the buildings are distinguished by their diverse formal styles. The collection is unified instead by a continuous ‘philosophical style’ driven by an ever-evolving search, an investigation of how humans live.

During their visit to New York, designboom spoke with Li Hu and Huang Wenjing to learn more about their practice, their book, and their approach to architecture today.

Li Hu and Huang Wenjing | image by designboom

Li Hu and Huang Wenjing | image by designboom

designboom (DB): Tonight you’ll be lecturing here at the Center for Architecture. And you’re launching a new book. Could you describe some of the main themes that you’ll be discussing?

Li Hu (LH): The book is an important project. It is a ‘counter project to projects.’ I want to compare the book to the practice: the projects we do as architects are always more intuitive, where the process of writing the book is analytical. In a way, we have turned the intuitive into the analytical. There are six projects in the book. If you draw the timeline, they overlap with some stretching very long and some very short. The book is linear, very different from the projects. In a way it forced us to put things in a linear fashion. With projects, each day is chaotic and the book cannot be more organized.

One of the most important parts of the book is a new manifesto. Throughout the whole journey of being architect, there’s a perpetual question: why architecture? What is architecture, what do we do it for, and how do we do it? That’s the reason for writing a manifesto.

The most important thing we wrote in the manifesto focuses on ‘connection,’ using the six cultural projects in the book. We build to connect three dimensions of three levels — between human and people, between human and nature, and between the human and the inner self. This is how we see the meaning of architecture, and we apply this in all six of these cultural projects.

The Sun Tower, image courtesy OPEN Architecture | more about the project on designboom here

The Sun Tower, image courtesy OPEN Architecture | more about the project on designboom here

Huang Wenjing (HW): In such an uncertain and fast changing world, a lot of things seem to be chaotic. But architecture has to be our anchor, anchor us back to this physical world. So what’s he talked about these, these connections that were important to us, and we’re trying to search for that in every project, we have the opportunity to build for even the research projects, where do you have a lot of other projects. So this book is just focused on cultural architecture, which I think it’s quite reflective of what the Chinese society is going through at this moment.

Everyone has probably seen or heard how China has built so fast over the past couple of decades. We always felt like our whole society builds too much too fast. When people’s basic needs of food and housing are satisfied, what do people need? People have other desires — cultural and spiritual needs. There is more demand for ‘food for the soul.’ In a way we happen to be there at the right time, and these kinds of projects just happen to fit into our nature.

Chapel of Sound, image © Jonathan Leijonhufvud | more about the project on designboom here

DB: Has your practice greatly evolved over the past decade?

LH: Work is a constant evolution, day by day. Because every day you hear something, you miss something, you hit a wall, there is a problem — you learn something. We’re always going forward, maybe sometimes we go backward (laughs) you never know.

We don’t carry ‘style’ as a burden. To me, ‘style’ is a commercial idea. We carry the ‘thinking’ forward rather than the style forward, so every case is a different case. Instead of linear evolution, it’s more of a searching, experimentation, exploration. It’s like hiking paths — you don’t know where you’re going. Just go.

UCCA Dune Art Museum, image © Tian Fangfang | more about the project on designboom here

DB: So your studio doesn’t have a continuous formal style in that sense, but you have a continuous philosophy?

LH: Exactly. It’s important that we ask, ‘How do you live as a human?’ You have your beliefs, not necessarily religious, but there are beliefs that you have.

DB: How do these beliefs of the user inform your designs?

LH: For example, if you believe in modesty — that humans should change their style of living on this planet to be more modest — that is a philosophical belief, or attitude to your work, which drives your approach to the project. Where do you place your building? How does the building touch the ground, and how much material do you use? And you don’t do obsessive decorative work. There are architects these days that are obsessive with decoration — they wouldn’t call them decorations. So I think modesty is an example.

Think about generosity. How do you design your building to welcome everyone, instead of in a way which preserves a daunting image.

Pinghe Bibliotheater, image © Jonathan Leijonhufvud | more about the project on designboom here

HW: Modesty is very important, and relating to what you said, being open is very important (LH: yes, openly generous). When you’re only focusing on the the strict, professional scope — material, craft — you could become very self indulgent. But you can open up and see that there are different people.

One time in my life, I realized that things we were obsessed with — joints, layout — nobody cares! (laughs) No one sees these details, but they are probably very costly and take a lot of energy. There are a lot of other things that we could do that would influence other people’s lives. That’s another reason we like to work on these public projects rather than private, because they touch so many people’s lives.

TANK Shanghai, image © Tian Fangfang | more about the project on designboom here

DB: How do you harmonize your values with those that use your spaces?

HW: In the end, I don’t think it’s in conflict. As we travel, and as we grow and see kids growing up, we understand more how the world works, and how society works. A lot of our thinking focuses on ‘how to make a place that works for everyone.’ At art institutions, for example, what works is that people don’t feel intimidated or they don’t feel it’s unrelated to them. A lot of times the magic lies in natural elements, so we bring gardens and people feel at ease. Being in the art center is like going to a park. To us that is quite important.

A lot of times people don’t see where the architecture is. They say the architecture makes a big statement as a strong object. But a lot of times we actually let the nature take over and people take over, you’ll see that at TANK Shanghai.

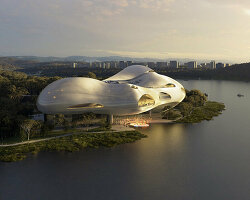

Shenzhen Maritime Museum, image courtesy OPEN Architecture | more about the project on designboom here

Shenzhen Maritime Museum, image courtesy OPEN Architecture | more about the project on designboom here

DB: When designing a gallery space, it can be difficult to strike a balance between how much the art itself should shine, and how much the architecture should shine. How do you find that balance?

LH: You can think of everything as music, and every work of architecture as a theater. You create a kind of ‘vessel’ for the action. How do you make your building exciting, inspiring without overwhelming the art.

HW: The format of art has evolved so much. At an art institute back in Beijing, we have noticed that a very small percentage of the work is paintings. Most of what we saw was installations, multimedia, and digital cross-discipline works. Art changes so fast while brick and mortar architecture changes very slowly. Once you build it’s hard to change. Nowadays the challenge becomes, ‘how do you build more flexible space more are space?’

Our UCCA Dune Art Museum is used mainly for installations. I do hear people say that a lot of visitors come to see the architecture instead of the art. But I don’t feel bad about it! (laughs)

LH: Well you shouldn’t! Look at some of the best examples of museum history. People go there, not just to see art — that would be boring, like a cigar box. The best museums require great, inspiring architecture. Of course, it should be functional, but inspiring beyond functional, with great work in it.

UCCA Dune Art Museum, image © Tian Fangfang | more about the project on designboom here

LH: One last note on the balance is between the radical and the poetic. That’s a hidden message in the manifesto. We need radical change in many ways. But it cannot be simply radical, or brutal. The causes of coexistence and the balance of the two, make a great architecture. If you look at all great architecture in history, they are all radical or poetic. To be able to do both, it’s rare. And we try very hard to do both.

architecture in china (1853)

architecture interviews (272)

OPEN architecture (24)

PRODUCT LIBRARY

a diverse digital database that acts as a valuable guide in gaining insight and information about a product directly from the manufacturer, and serves as a rich reference point in developing a project or scheme.