THE 2023 AUSTRIAN PAVILION PROPOSAL BY AKT & Hermann Czech

Architecture collective AKT and Austrian architect Hermann Czech pair up to curate the Austrian Pavilion for the Venice Biennale 2023. During their conception phase, the design team planned to open part of the temporary pavilion to Sant’Elena, the Venetian neighborhood residing just behind the grounds of the Biennale, separated only by a wall. Opening up a pathway meant Venetian residents could freely access the pavilion without paying an entrance fee, hence creating a social circle and exchange, an interaction between the transient space of the pavilion and the permanent home of the residents.

When the design team proposed the idea, Venice Biennale and the Monuments Office said no to the plan. In an interview with designboom, AKT & Hermann Czech share that the reasons behind this decision were that this would create a precedent and that the indivisible use of the pavilion and the Giardini as monuments would be compromised through public access. ‘Our project has been conceived as an invitation to the population of the neighboring district to freely use the space in the pavilion; to cooperate with right-to-the-city initiatives to intensify their existing dialogue with the Biennale; and to the Biennale itself to get involved,’ AKT & Hermann Czech tell designboom.

header: the division of the symmetrical pavilion carried out, photo © Clelia Cadamuro | image: view from the courtyard of the Austrian Pavilion over the wall to Sant’Elena, photo © Clelia Cadamuro | images courtesy of AKT & Hermann Czech

What role will the Biennale play in the future of Venice?

In January 2023, AKT & Hermann Czech reprised their proposal, this time by building a temporary bridge made of scaffolding to connect the adjacent district and the Austrian pavilion, still allowing free access between the spaces but without opening up a pathway. For the second time around, Venice Biennale and the Monuments Office declined the redesigned pitch, just weeks before the architecture exhibition begins.

‘This opening of one half of the pavilion was refused—yet without a final official notification so far —because those in charge did not want to set a precedent. But it is precisely such a precedent that would be desirable if Venice’s most important cultural institution, the Biennale, does not want to increasingly decouple itself from its host, the city of Venice and its population,’ the Austrian pavilion curators share with designboom.

With two of their plans to open the pavilion towards the city being rejected, AKT & Hermann Czech invert the refusal into a curational lens that delves into the kind of role the Biennale will play in the future of Venice. For its exhibition inside the Austrian Pavilion, the architecture collective and Austrian architect question Venice Biennale’s spatial policy, all while unraveling what its slogan this year ‘The Laboratory of the Future’ truly entails.

the tiered seating setup in the assembly room of the ‘city half’ is ready | photo © Clelia Cadamuro

‘this failure will become the political content of the exhibition’

Even before they received a red light on their attempt to bridge Sant’Elena with the Austrian pavilion, AKT & Hermann Czech had already toyed with the idea of rejection. AKT & Hermann Czech open this up with designboom and add that ‘The Biennale regularly rejects concepts, which are then revised or completely changed. However, we have always ruled out changing our project due to the subject matter dealt with; rather, this rejection should then be made visible and tangible in the exhibition.’

Now that their inkling has become the truth, the inaccessible empty space that should have been dedicated to the Venetian residents is slated to host the Biennale visitors for them to witness the remnant of a missed opportunity for social participation. ‘Instead of a bustling laboratory, the pavilion’s half originally intended for the public is now a visible vacancy, a permanent construction site underscoring the central question of the project as to what role the Biennale could possibly play in the city.’

the built stairs leading up to the base of the bridge near the courtyard wall of the Austrian Pavilion | photo © Clelia Cadamuro

in conversation with AKT & Hermann Czech

The Vienna-based architecture collective and the architect embarked on a research venture for over a year and a half alongside local researchers, and the results they gathered uncovered that in 2022, the population of Venice fell below its historic low of 50,000. Reasons such as a tourist monoculture, the economic exploitation of urban space, the concurrent processes of displacement, and the loss of essential infrastructure form part of why residents are exiting the city. The finding about the depopulation of the city was a reason the design team wanted to connect the remaining Venetian residents with the Biennale visitors.

Sant’Elena is one of the few remaining neighborhoods in Venice still inhabited predominantly by Venetians. AKT and Hermann Czech wanted to shift the separation between the Biennale and the city into the pavilion and to hand over space to the urban public, a ’Laboratory of the Future’. But now, drawn from the decision of the Venice Biennale, these ideas remain just as desires. designboom speaks with the curators to open up the discussion surrounding the rejected proposals, the present plan to use the vacated space, and what role can the international architecture exhibition play in the future of the city of Venice. Read our conversation in full below.

courtyard of the pavilion with a stair tower and bridge-segment of the planned connection | photo © Clelia Cadamuro

designboom (DB): What was the original plan of AKT & Hermann Czech for the Austrian Pavilion at the 2023 Venice Biennale, and why was it rejected?

AKT & Hermann Czech (AKT & HC): The project has been conceived as the Biennale’s turning to the surrounding city: not in the form of further expansion like over the past decades, but in the form of giving up space and thus as a reversal of said spatial practice, which in recent years has also been increasingly criticized by the international press. The pavilion should have been divided. One-half of it should have been ceded to the population and made freely accessible by the city administration as a place of assembly.

In our opinion, the power of disposal over space is an essential precondition for the people’s participation in the city. In Venice, however, space is a highly contested resource, as the available land is limited. Its economic exploitation, coupled with natural influences such as regular floods and high maintenance costs, leads to a shortage of affordable space. This, in turn, has resulted in a displacement of everyday culture from the historic old town that has been going on for decades. Our project has been conceived as an invitation to the population of the neighboring district to freely use the space in the pavilion; to cooperate with right-to-the-city initiatives to intensify their existing dialogue with the Biennale; and to the Biennale itself to get involved.

The pavilion is located on the northeastern border wall of the Giardini premises. All that would have been needed would have been a minimal temporary intervention to connect it to the city. But this opening of one half of the pavilion was refused—yet without a final official notification so far —because those in charge did not want to set a precedent. But it is precisely such a precedent that would be desirable if Venice’s most important cultural institution, the Biennale, does not want to increasingly decouple itself from its host, the city of Venice, and its population.

an opening subsequently closed again in the outer wall of the Giardini area, directly behind the Austrian Pavilion: a temporary access from the city had originally been planned here | photo © AKT & Hermann Czech

DB: How does the team plan to move forward following the dismissal of the second proposal?

AKT & HC: A possible rejection has been considered in the concept from the very beginning. The Biennale regularly rejects concepts, which are then revised or completely changed. However, we have always ruled out changing our project due to the subject matter dealt with; rather, this rejection should then be made visible and tangible in the exhibition.

The Austrian Pavilion is therefore no longer merely a space for exhibits containing information on the thought of ‘participation’, but it becomes an exhibit in its own right through its temporary conversion: it ‘spatializes’ the division and the relationship between the city and the Biennale.

In view of the rejected opening towards the city, the architectural setting planned for the project has therefore been realized except for the actual connection to the city, which has not been met with official approval yet. Instead of a bustling laboratory, the pavilion’s half originally intended for the public is now a visible vacancy, a permanent construction site underscoring the central question of the project as to what role the Biennale could possibly play in the city.

view to Sant’Elena: the courtyard wall as a hard border | photo © AKT & Hermann Czech

DB: How will the vacancy of one half of the pavilion be used in the exhibition, and what questions will it raise?

AKT & HC: The empty half of the pavilion will be open to visitors on a limited scale. The exhibition and the comprehensive publication accompanying it analyze the Biennale’s current spatial practice. The mega exhibition’s constant expansion and today’s forms of exclusion of the population from the spaces used by the Biennale will be documented and contextualized by local researchers and initiatives.

If initially external country pavilions and events were primarily housed in official buildings, churches, and cultural institutions, looking at the Biennale Arte 2022 shows that the exhibitions have long since occupied the entire spectrum of building types across the city: former workshops, manufactories, old shops, and even abandoned flats exemplify the displacement of everyday urban life by tourism and international high culture.

The Biennale itself has operated its own real estate exchange for years. Private agencies act as intermediaries or as owners themselves, acquiring business premises, commercial properties, and apartments to be used as exhibition spaces. The Arsenale, covering an area of almost one-tenth of the entire old town and thus one of the most important potential spaces for sustainable urban development, has become equally contested.

view towards the wall, separating the Biennale from the city side of the pavilion | photo © Clelia Cadamuro

AKT & HC (continued): While complex ownership relations between the state and the municipality have contributed to the fact that an overarching concept for integrating the former shipyard complex into the city has never come about, the Biennale has continuously expanded there since the early 1980s, most recently in 2022. This primary use for paying cultural tourism has been criticized by numerous initiatives, which have called for a public passage through the Arsenale and its use in the interest of the local population for years.

Now the vacant half of the pavilion, including the prevention of the spatially configured concept of participation through the Biennale and the institutions involved, has become one of the central exhibits. The question arising from this can best be formulated in the words of the Venetian initiative We Are Here Venice: ‘The question is not whether Venice should host the Biennale: it is a significant reality. But should Venice be getting more from the Biennale, and vice versa? Can an organization showcase references to social and environmental justice without specifically addressing these issues in its operations?’

detail of the dividing wall | photo © Clelia Cadamuro

DB: In your opinion, what role can the International Architecture Exhibition play in the future of the city of Venice?

AKT & HC: This is exactly the question we seek to pose with our contribution, underpinned by another issue: What role has it already played once? ‘Partecipazione’ was a core demand of the first architecture exhibitions of the 1970s and 1980s that were held in the context of the Biennale. Artists and architects were asked to work on site with the city and its problems in a context-specific way. The political, social, and spatial realities of Venice were to become part of the content of architectural exhibitions.

If one understands the International Biennale of Architecture not as a profitable exhibition container but as a globally financed vehicle for improving the socio-spatial realities of Venice, it becomes obvious that an internationally exemplary counter-model to the current exploitation of urban space could emerge from it. Is that utopian? No, because precisely this approach already existed in the past.

To put it in the words of one of the former directors of the Architecture Biennale, Francesco dal Co: ‘We were interested in encouraging people to come to Venice to study the problems of the city, and to use those problems to create the occasion for a project. […] This was an approach that all of us Italians shared – Vittorio [Gregotti], Aldo [Rossi], myself, etc – and it has been lost completely…’ [Francesco dal Co, director of the Venice Biennale of Architecture 1988–1991]

plan’s first model | photo © Theresa Wey

DB: What are some of the city issues that will be discussed in the alternative locations organised by local residents and initiatives?

AKT & HC: The program planned for the duration of the Biennale is an expression of the neighborhood between curated mega events and everyday urban culture—on the one hand, there will be events organized by us together with local initiatives and researchers, and then there will be events self-initiated by residents of the neighboring district on the other.

Both program lines, which were originally intended for the assembly room in the pavilion, have now been deliberately shifted to precarious residual spaces in Sant’Elena so that they will still be accessible for free. The curated events are to take up the regional discourse about the Biennale’s role in Venice that has been going on for years.

There will be lectures on specific sites, such as the Arsenale, the Giardini, and the phenomenon of collateral exhibitions. City walks in the Castello district and various activities related to Venice’s most pressing issue, which is housing, will place those contributions in a wider context. These events will take place every two weeks on Saturdays.

In addition, the residents have developed a dense independent program in the district, which, although associated with the Austrian Pavilion, is not primarily aimed at a Biennale audience, but rather at cultural self-empowerment and the strengthening of existing social cohesion. This self-awareness in the confrontation with the Biennale as an institution has actually been strengthened by its rejection of the proposed project.

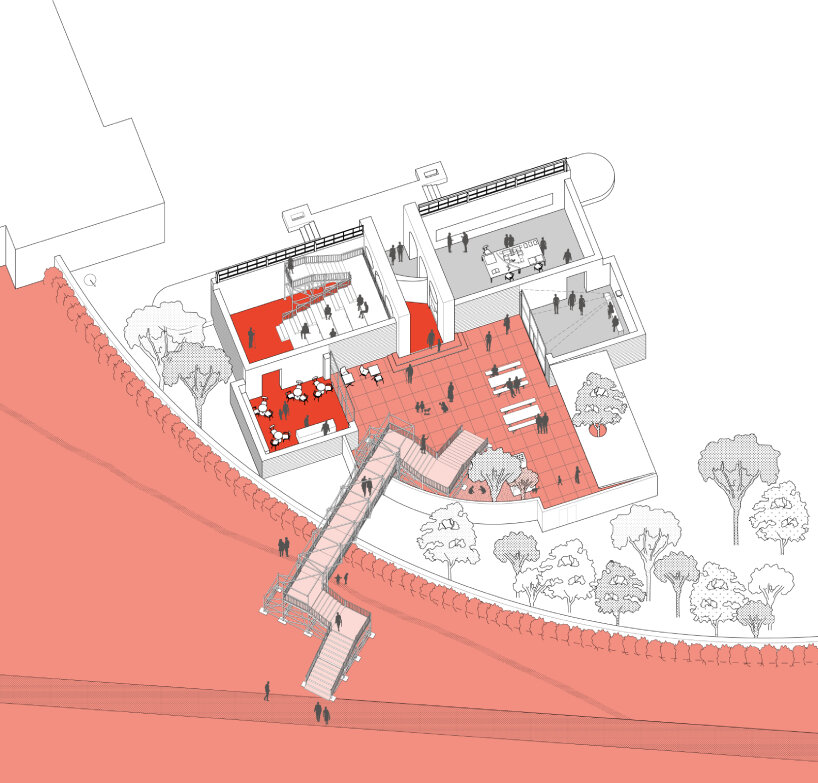

axonometric image of the second variant with bridge (rejected) | image © AKT & Hermann Czech

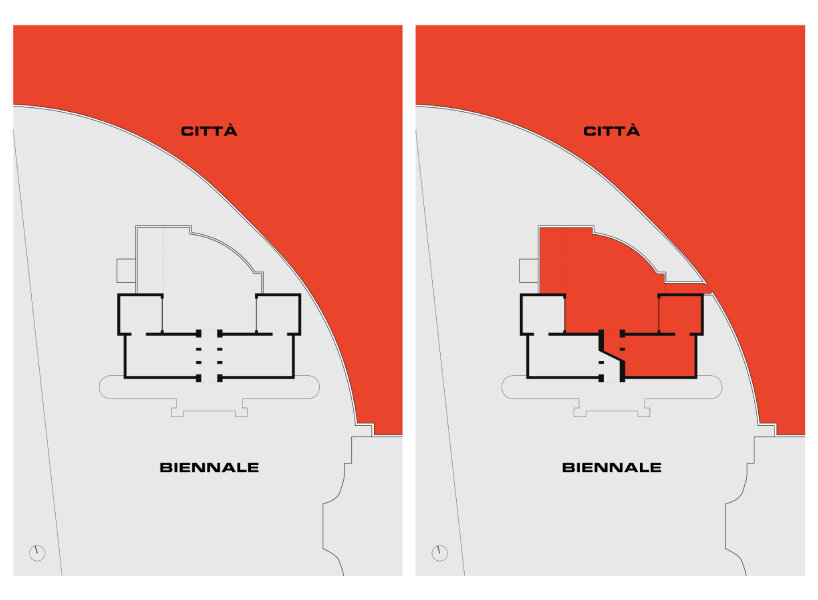

left: Austrian Pavilion and Giardini wall | right: planned opening by breaking through the wall temporarily | diagrams © AKT & Hermann Czech

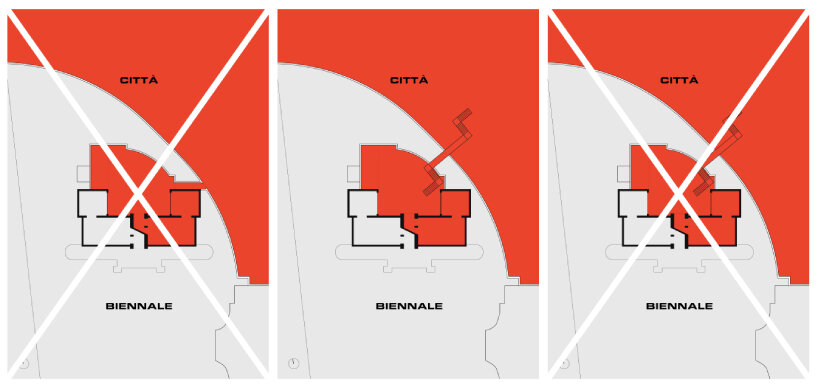

left: rejection of the wall breakthrough | center: submission of the bridge across the Giardini wall | right: rejection of the bridge | diagrams © AKT & Hermann Czech

project info:

name: Austrian Pavilion at the Venice Biennale 2023

curators/designers: AKT, Hermann Czech

commissioner: Austrian Federal Ministry for Arts, Culture, the Civil Service and Sport

project management: Katharina Boesch, Julia Bildstein, section.a, Vienna

AKT team: Fabian Antosch, Gerhard Flora, Max Hebel, Adrian Judt, Julia Klaus, Lena Kohlmayr, Philipp Krummel, Gudrun Landl, Lukas Lederer, Susanne Mariacher, Christian Mörtl, Philipp Oberthaler, Charlie Rauchs, Helene Schauer, Kati Schelling, Philipp Stern, Harald Trapp

temporary pavilions (442)

venice architecture biennale 2023 (40)

PRODUCT LIBRARY

a diverse digital database that acts as a valuable guide in gaining insight and information about a product directly from the manufacturer, and serves as a rich reference point in developing a project or scheme.