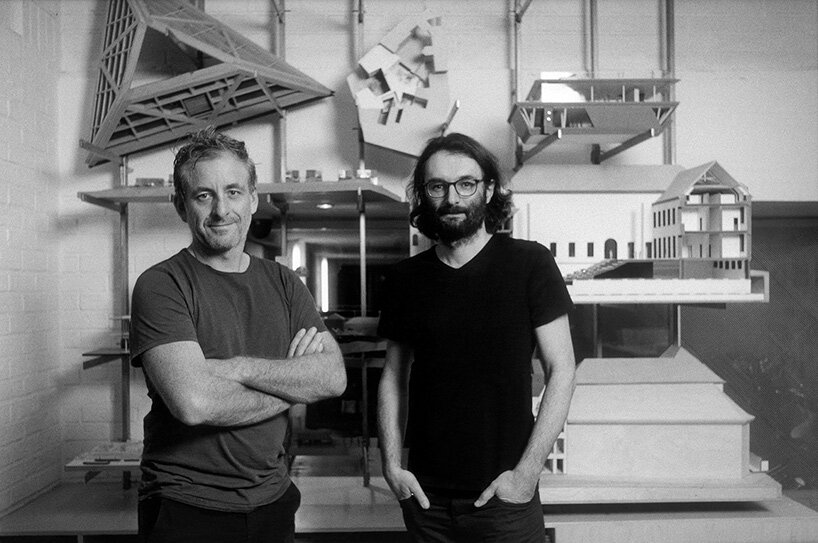

in 2005, olivier camus and lydéric veauvy, friends and classmates from architecture school, decided to create their own firm. ‘I don’t recall having made any individual project without consulting each other,’ veauvy tells designboom. ‘the idea to create something together was always there during our studies, but it was not pronounced.’ 16 years later, TANK is still going strong and has since developed a reputation for creating sensitive architecture that resonates with its context.

as the firm is based in lille, a city in northern france close to the belgian border, much of the studio’s work is informed by the region’s weather, climate, and materiality. ‘our projects are very attentive to light, we are very much aware that the north and the south, the east and the west, are not fixed realities on a cross in a map, but rather much more subtle according to the seasons,’ explains olivier camus. in our in-depth interview below, the duo discuss why wood is a ‘magical’ material and how the role of the architect has changed over the years.

TANK’s atelier in lille, france | image © TANK

designboom (DB): can you start by telling us how you met, and why you decided to set up an office together?

lydéric veauvy (LV): we entered saint luc in tournai in the same year, and quickly formed a friendship based on exchanges and discussions around architecture. we built a demanding and uncompromising bond with each other based on how we approach architectural design. I don’t recall having made any individual project without consulting each other. the idea to create something together was always there during our studies, but it was not pronounced. we had each come a long way on our own, but then after taking the time to share our motivations, and establish the objectives and balance of an architectural partnership, we decided to create TANK.

olivier camus (OC): we developed a real rapport as far as group projects are concerned, out of friendship. in addition to that rapport, we wanted to work with a strong team to think carefully about how we would approach architectural design.

2+2 houses, villeneuve-d’ascq, france, 2005 | image © julien lanoo

DB: in what ways does the weather, climate and materiality of northern france influence your projects?

LV: the geography is, of course, pertinent to a project. more broadly, it is through the relationship to the landscape, to materiality, to the poetry found in the passing of time, that our projects and the choreography of their forms uncover their ‘atmospheric capacity’: the variations of the sky, the alternations of rain and sun, and rain under the sun, certainly invite us to express the course of water, the overflows, the play of shadow and light, matter as a partner in the variations of seasons, an art of building that is conscious of these elements, and the passing of time.

OC: our projects are very attentive to light, we are very much aware that the north and the south, the east and the west, are not fixed realities on a cross in a map, but rather much more subtle according to the seasons. the materiality of the north, although we have used brick extensively, is not necessarily an influence. it is above all the context, the local, low-carbon materials, and the know-how that interests us. it is also very difficult to find these right materialities in an industrialized and globalized world.

school buffon, roubaix, france, 2011 | image © julien lanoo

DB: you often use wood in your projects. what characteristics of the material make it desirable to you?

OC: wood is a natural material, not an extraction material. it’s very tactile, it feels and smells good, has beautiful sonority, and is easy to work with. one could say that is one of the rare materials that is accessible to everyone, there is a certain richness, you can make anything with wood: frameworks, façades, furniture, anything, that’s why it’s quite magical. it gives access to an understanding of the building. we went through an opaque phase where the buildings were somewhat abstract. we promoted the expression before construction. we often struggle with that, the temptation to be more sculptural and abstract, and the desire to be more readable, more artisanal, etc. — wood for such expressions bears many qualities. it is with the projects built in wood that we are able to be most creative and free in the office.

LV: we try to develop precise details, but simple solutions. the use of single materials means we can preserve quality in terms of composition, framing and proportions; it supports the physical and visual force of the buildings. the quality of a building should not lie solely in the material you add onto it.

maison mouvaux, lille, france, 2019 | image © julien lanoo

read more about the project on designboom here

DB: we recently published your project ‘maison mouvaux’. what was the brief for this house, and what did you set out to achieve with your design?

LV: the clients wanted a ‘secretive and simple’ house, respectful of the largely wooded site. our ambition was to create an architecture that eluded the size of the program, and had the ability to slip into and towards the tree line on the site. very quickly, the idea of two very strong experiences: being a ‘protector’ in the trees, one who experiences all the sequences offered on the ground floor, and one who benefits from very strong inside and outside: a project capable of multiplying the poetic and sensitive composition of sky, trees, and the very strong presence of the site’s landscape.

maison mouvaux, lille, france, 2019 | image © julien lanoo

OC: we explored the notion of ‘secrecy’ and quickly started working on the interlacing of spaces — spaces that are open to one another, and open to the garden, while at the same time remain hidden and private. it’s like a bourgeois house in which you find rooms for each purpose, but also modern. we used different variations of wood in different nuances, which allowed us to explore this duality and achieve a balance between intimate and open, comfortable and welcoming, as well as open to the exterior and to the panoramic view of the garden at the same time. there are almost no corridors in the house and we’ve worked intensively on the perspectives: the relationships between the different rooms, the interior perspectives, moments and relationships between the garden and the interior that we uncover throughout the whole house. these are all adapted to little domestic rituals, small moments of life.

léonard de vinci technical college by TANK + COSA, saint-germain-en-laye, france, 2020 | image © camille gharbi

DB: do you both work on all stages of a project, or do you find that you have different strengths?

OC: our office resembles a house, and our team works like a big family. we know each other very well, and we find quickly the common thread of a project. the starting point for the projects takes the form of many discussions within the group, supported by sketches and collective models. we spend a lot of time researching and model-making, but the principal tool remains the drawing. we don’t work by hypotheses. in the process of our work, we arrive very quickly at the objectives, and our team develops one concept around the objectives and where we want to go.

LV: we work together on all our projects throughout the sketch, competition and pre-planning phases. on our first projects, everything is discussed, exchanged and co-written within the time available. in the following phases, it is often one of us who becomes the referent due to circumstances, the need to be immersed in the project management team, and according to the amount of precise data that needs to be incorporated into our reflection. we trust each other, but we constantly try to maintain this critical double reading which takes projects to the next level — but sometimes time constraints can limit us.

the timetable of a project is long and, sometimes, we alternate taking on the role of a ‘referee’, in particular in terms of the direction of the design during the construction phase. a priori, we do not have different areas of expertise, but requirements and skills may differ depending on the area or the time. we often serve as the ‘complementary muscle’ of one another and alternate depending on the subject.

conceptual model, la minoterie, roubaix, france, 2008 | image © TANK

DB: how do you develop projects with your team? do you prioritize model-making and sketching over a more digital approach?

LV: our work methods are very empirical and intuitive, the process differs depending on the subject, the time available, and the number of projects that need to be designed simultaneously. we like to use both craft tools, as well as the art of the hand, the ‘thinking hand’: sketches, diagrams, tracings, cutting and drawing, models. we come from a generation that learned to design and draw by hand while experiencing the advent of computers and their infinite possibilities.

furthermore, we also use digital tools when they offer other means of design (light, reflection, precision, immersion, substance, etc.). we quickly integrated a model workshop in the office, coupled with an in-house development of research and architectural visualizations. in the end, what matters is the ability of a tool to further help us with the design of a project.

55 housing units, nantes, france, 2008 | image © julien lanoo

read more about the project on designboom here

DB: you recently carried out a research project on the question: what determines the qualities of the dwelling for the user? what conclusions did you draw from this study?

LV: we have been working on this issue in practice for years. with the research project that is now underway, we aim to structure this approach, to define a precise state of the art on this issue, and to develop new research methods. until now, the research applied to this project has been at the heart of this initiative. we have identified a number of fundamental aspects for these qualities of a dwelling:

the capacity of a housing project to create a sense of togetherness and neighborliness; the importance of the typological quality which stems from the uses and functions and thorough work on the ‘furnishability’ of the space. a good dwelling should be able to accommodate multiple uses and as many ways of living as there are inhabitants. there are as many kitchens as there are families, and if the plan fails to allow for these variations, the dwelling can quickly reach its limits; a well-designed bedroom also allows the housing typologies to adapt themselves to the evolution of the family structure; the importance of gradients of intimacy, the capacity of the project to offer an interior life to the community and the city, a presence, but also intimate places; the relationship with the human being is essential; the project’s ability to seize the views, the light, and to experience the context in a qualitative manner.

housing project in luxembourg | image © TANK

LV (continued): our approach to housing strays far from generic principles. the project we are conducting in luxembourg, for example, is an experiment with 100 dwellings that are designed to be unique through a system of variations that offers buyers choices that will affect the architectural grammar of the project. we like to find strategies that bring the inhabited closer to the human and that are critical of the housing that is produced.

halle de calais, calais, france, 2015 | image © julien lanoo

OC: in housing, but also in all architectural typologies, we are aware that the completion of a project is not where the research and the work of the architect ends — the critical engagement should carry on. our aspiration is that the projects are sustainable and adaptable in the long-term, and to see how, after a period of time, the planning and our anticipations meet the reality of the users.

I firmly believe that we have completely stepped out of functionalism. today, architecture should be able to serve and live at all times, and not just to one specific purpose or program. in the project of the halle de calais, for example, we imagined a variety of activities that can inhabit the spaces in the concept stage of the design, but the building really did create its own life and has been used over the years for so many different things, and catalyzed a very big change in the area. the question of the post-occupancy of a project is a very important one.

school in clichy-sous-bois, france, 2015 | image © julien lanoo

DB: you are both involved in teaching. what impact does educating others have on your own work?

LV: teaching requires referencing and properly framing educational objectives and achievements. the practice of teaching is also a lifelong training, a cultural environment protected from the needs and constraints of practice. this develops a spirit of synthesis and an ability to read a project and grasp its fundamental elements. these aspects strengthen our convictions, our culture, and a certain understanding of the world. it is a great motivator not to fall asleep and to continue to progress.

OC: we both became teachers at the faculty of architecture, architectural engineering and urban planning (LOCI, site of tournai) at UCLouvain, and for both of us, it has provided us with the richest moments in our everyday lives. the profession has changed: before, the architect was there to draw plans, to design the layout, to be creative. today, the engineers are better than us at drawing. they use in-house charters and high-performance tools. what lies at the core of our activity is creativity, a capacity for in-depth thinking, an ability to see the big picture, and a sense of ethical responsibility. that’s why at the school, for years, I’ve stopped giving a specific program to the students, instead we define a problematic, which allows the students to research, question and find different forms of usage, and how they can be linked to the given context. school is more like a laboratory for questioning. our point of view is that we’re here to train people who will be armed to enter the profession: creatives with an added value, not just good draftspeople. otherwise, we’re likely to be swept away, especially where increasingly common so-called ‘design-and-build’ projects are concerned. ultimately, it’s essential that the school should teach architects to believe in their own creative ability, and to use that ability to serve the community.

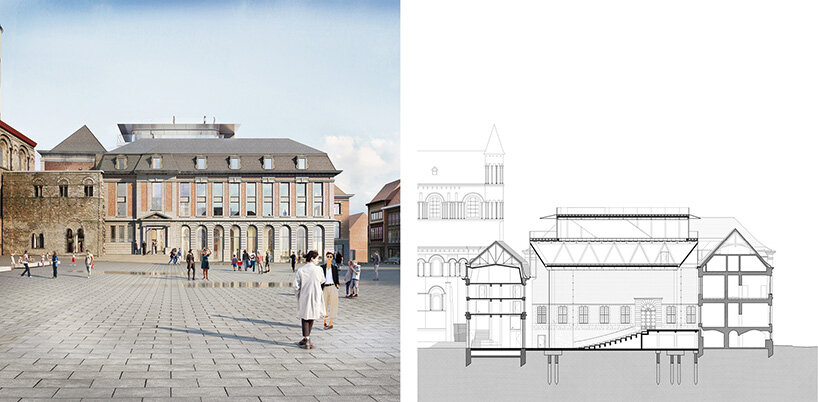

ongoing project for the cultural project le carré janson in tournai, belgium | image © TANK

DB: what advice do you have for today’s students and young architects?

OC: to define the objectives without the way to get there. there is a certain conservatism in france when it comes to competitions, and the ideas for altering the given program or suggestions can penalize the architect. my advice would be to be curious about everything, not just architecture, but everything that surrounds us. an architect is good as a result of his interest in the world, and not just his interest in architecture itself: to be optimistic, to think more broadly, and to follow a cross-disciplinary approach to architecture.

LV: to be critical. design is fun. you can fail, but you have a duty to try, draw, test. architecture is a constructed art. architecture, like art and cinema, produces emotion. it’s a beautiful profession when you place this idea at the heart of the practice.

ongoing project for the international campus lesaffre in france | image © TANK

DB: what projects are you currently working on that you are particularly excited about?

OC: one important project under construction is the reinvention of a UNESCO world heritage site in tournai. the plot encompasses buildings from different time periods that have not been used for the past 30-40 years, and the question was how to reinvent this place and a sense of urgency that would make it universal through a contemporary and respectful intervention. this project is planned to become a place of entry to the city, a place that can allow the visitor to discover the culture and history of the city, a touristic destination, but also one with offices dedicated to professionals, conference rooms, an auditorium, as well as places dedicated to everyday life — meeting rooms, a restaurant — it’s a hybrid space that acts as a place for the inhabitants of tournai, a place for tourists, a place for professionals. a site that will adapt to all sorts of the needs.

lydéric veauvy (left) and olivier camus (right) in their office in lille, france | image © julien lanoo

LV: we are interested in sites with a history, and a strong atmosphere, in the capacity for innovation, and exploration that a project offers how to redefine our practice, and face the problems of the world in order to develop a resilient and virtuous architecture. this is what excites us a lot, and what worries us as well.

architecture interviews (267)

TANK (3)

PRODUCT LIBRARY

a diverse digital database that acts as a valuable guide in gaining insight and information about a product directly from the manufacturer, and serves as a rich reference point in developing a project or scheme.