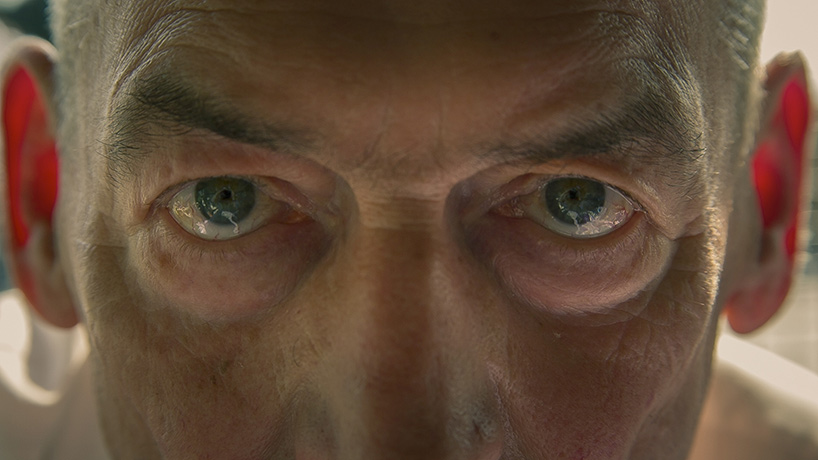

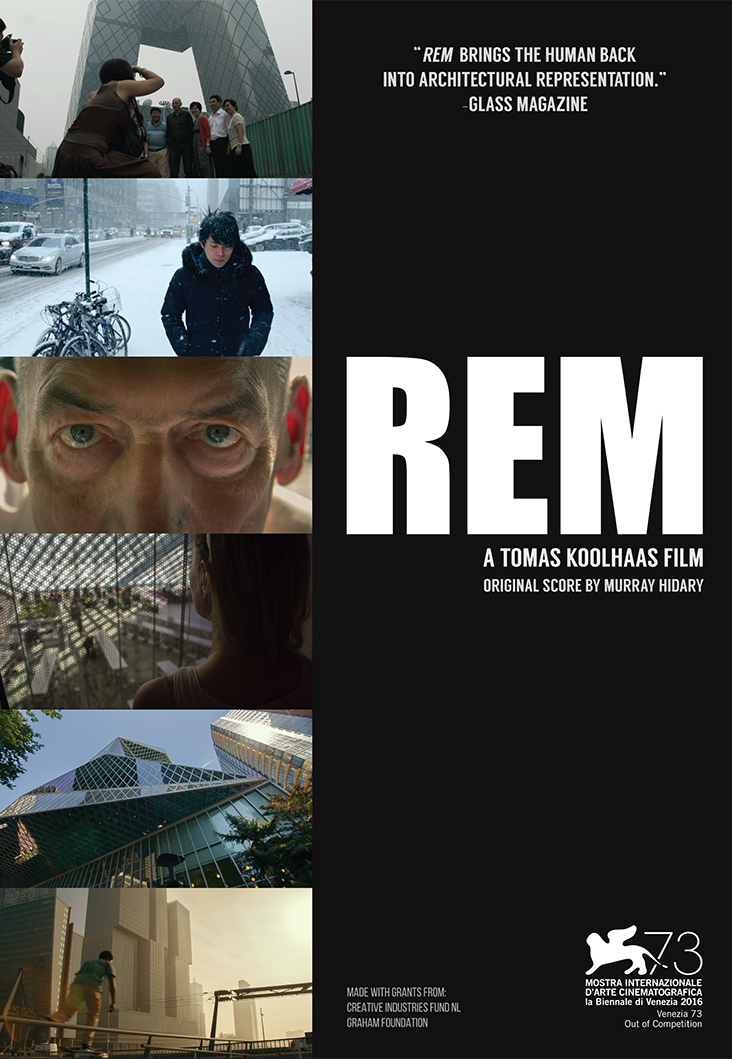

in 2016, after years of chronicling his father’s work around the globe, los angeles-based filmmaker tomas koolhaas released ‘REM’ — a documentary that gives its audience unprecedented insight into the life of one of today’s most acclaimed architects. the film intimately explores rem koolhaas’ life, working methods, and philosophy from a first person perspective — a viewpoint intended to induce the feeling of being inside rem’s head. this personal approach continues in the film’s documentation of the buildings’ users, whose lives are also explored in relation to rem koolhaas’ architecture.

ahead of REM’s release on various formats in the netherlands, the US, and the UK on may 1, 2018, designboom spoke with tomas koolhaas as well as the film’s protagonist — rem himself.

tomas and rem koolhaas

designboom (DB): the film shows rem interacting with a range of people, from builders to artists and curators. how important is a variety of voices in the creative process, and the successful development of a project of any kind?

rem koolhaas (RK): each architectural project is subdivided in phases. roughly speaking you could say: exploration, concept, project development, construction, occupancy, each of these implies a vast variety of interfaces, interactions, negotiations, collaborations, visits, travel, discussions. I would estimate that for a project such as the qatar national library, at least 500 interactions were important: 2/3 maybe as part of the formal design and realization process, and 1/3 in the form of informal consultations, observations, how the building is made and received… you have to deploy a huge scale of actions: you have to impress, seduce, impose, rationalize, convince. this polyphony of voices cuts through all generations, interests, social layers and nationalities… it is actually one of the great glories of making architecture.

the movie documents rem koolhaas as he works and travels around the world

tomas koolhaas (TK): as a filmmaker it is very important. for example, of the very few people who advised me during the making of the film, none of them were architects, and often not even filmmakers, but just people who are perceptive and original thinkers. that was on purpose, because I wanted to avoid the traditional ways of thinking, both in terms of cinematic conventions, but also architectural conventions and ideologies. most architecture films are made by architects, or people that studied architecture or used to be architects. in a way they are the worst person to make a film about an architect, because they have been imbued with such a specific way of looking at architecture. when I look at architecture I see it from the perspective of narratives, rather than intellectual concepts, or from a technical perspective. this allows for lay people to appreciate the film because narratives resonate more with most of us than technical ideas do.

casa da musica, porto, portugal (2005)

DB: the idea of disconnecting from/objectively reviewing one’s work is emphasized in the film. how do you find the practice of looking back on existing projects? can you recall a particularly strong emotional response?

RK: where the logistics of architecture suggest a never ending flight-forward, a rush to the next realization, one of the luxuries the film allowed me is to re-visit either through tomas’ vision or by visiting ‘older’ buildings together, a degree of retrospective appreciation. I discovered that retrospect does, for me, not imply looking at your own structures, but on the contrary it allowed me to look as if they has been done by someone else, and been there forever. separate from all the incidents, tensions, breakthroughs and setbacks – I could see them for what they were and experience them as a mere visitor…

TK: since I also edited the film and shot it, I saw the footage even more than the average director. so it’s an interesting experience of refining something until you feel it can’t change in any way that will make it significantly better. then you have to watch it another 100,000 times, and then you cross over into almost contempt of it. at that point you are really forced to see it from an objective perspective. as rem says in the film ‘as if someone else made it.’ which is a unique and interesting feeling. you finally stop thinking about this shot being slightly out of focus or this shot being too long and you can just view it as a whole, as an experience.

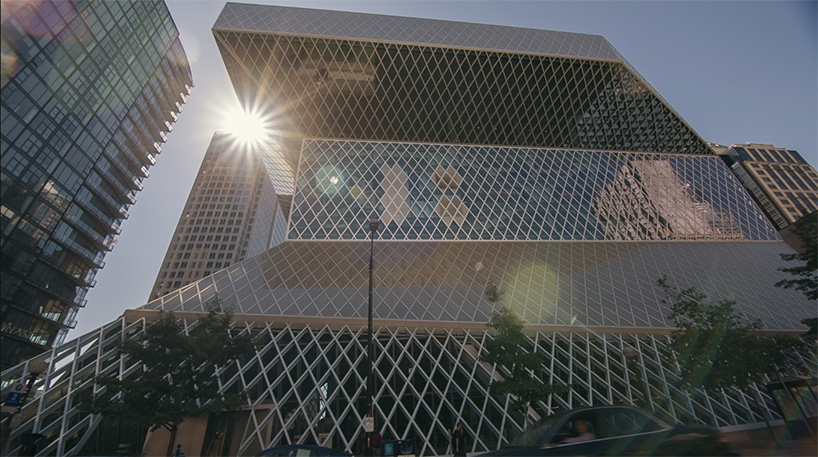

seattle central library, seattle, USA (2004)

DB: the production of films and buildings share similar processes, one of which is editing to refine the end result. how important is editing as part of the creative process? do you often have to let go of ideas you may have once been very attached to?

RK: for me, editing is the most crucial ability for any artist. I feel privileged to have experienced editing both of images and of the written word early, before I became an architect. editing = sequencing, and sequencing is crucial to film and architecture. in each project, important concepts on ideas do not make it to the end — you start with a kind of exaggerated fullness, and need to throw some out like ballast in a (hot air) balloon — but of course, too many ideas is better than too few.

seattle central library, seattle, USA (2004)

TK: editing is always important in films but in documentaries one could say that the editing is the film. it’s an interesting inversion of the process of making a narrative feature film, where you have a script and then you shoot the script and then you edit the shots basically as it was described in the script. with documentaries you (hopefully) have an idea of what you want, then you turn up with your camera and there is no guarantee you are going to get what you wanted, it may just not happen. for example, I wanted to film only buildings in use and sometimes I would get there and there was no one using it. so you end up with some shots that relate to your original concept or themes but others that don’t. the editing process is where you somehow make that all into one cohesive narrative. sometimes the only way of doing that is by having a non-linear production schedule, so you shoot, then you edit, then you realize you still need X shots or X voice-over and then you have to find of way of recording those.

seattle central library, seattle, USA (2004)

DB: both of your work also involves recording and documenting. is the notion of a legacy of work a driving force for you?

RK: legacy plays a minor part in my own considerations, most energy is consumed by the complexities of realization. but fortunately, in our organization it is a crucial issue — to convince client to ask us to do new work, and to inform our designers of the essence, thinking, inventions, and ambitions that we were able to incorporate in earlier work, often with significant collaborators… only a small percentage — 5%? — of an architect’s thinking is realized, so it is important to convey that other 95%.

seattle central library, seattle, USA (2004)

TK: not really. it’s hard enough to make a project that works individually without thinking of its place in some kind of larger context of a legacy or body of work. I also just tend to think more in the present, the idea of a legacy either seems retrospective or prospective. looking back to see how everything connects or looking forward to how it will be defined as a whole in the future, I don’t find either of those to be very productive compared to thinking about the project(s) I’m currently working on and how they work in and of themselves.

CCTV headquarters, beijing, china (2012)

DB: swimming is shown in the film as an integral part of rem’s day. do you keep any other rituals that aid your creative, physical, or mental well-being? on a personal level, how important is the idea of a prescribed set of daily actions? conversely, is changing your daily routine advantageous?

RK: the only way to handle the fundamental unpredictability of a career in architecture is to insist, where possible, on a foundation of physical and mental routine — i.e. to swim in the same pool, to eat in places you know, to sleep in familiar rooms. the sheer variety of commissions, conditions, contexts, creates enough ‘change’…

TK: I think both are important/advantageous. in the film rem talks about ‘movement,’ being vital to him. that’s a big theme within my life too. I am known among my friends for not being able to sit down for long periods of time, and for moving around geographically a lot. there are also daily staples within that movement, nature is one, being physical is another. I’m lucky I live in LA so the two can be combined easily either in the ocean or the mountains that are abundant here. for me the important changes in the daily routine come in the form of travel and work.

de rotterdam, the netherlands (2013)

TK (continued): in the film rem talks about how each place he’s worked in has changed his way of thinking, I see that with the places I’ve lived and worked in too. for example growing up in the cynical, somewhat dark mentality of london, then moving to LA and being exposed to a more hopeful, mystical, almost esoteric philosophy was very useful. I think the best thing you can do as a human being is doing things that make you uncomfortable, going to places you feel uncomfortable, moving somewhere you don’t know anyone, taking on jobs that make you uncomfortable. when I first started making the film I really disliked talking in front of groups of people, so I intentionally accepted as many Q&As or talks in front of very large audiences. it’s been a super powerful experience. what you can extract from a situation like that when you are open and not fearful is almost infinite. that’s become the most enjoyable part of the whole process for me.

villa dall’ava, paris, france (1991)

DB: the role of/relationship with the media is explored in the film. with a background in journalism, how has rem’s relationship with the media changed over time?

RK: it is not that my ‘relationship with media’ has changed — it is the media themselves that have changed. until roughly the 90s, the work was the focus, now it is the person. the review has been replaced by the interview — the interview implies almost by definition, an invasion of privacy, or at least, a pushing of privacy’s borders… instead of reading some good or bad review of your work, you constantly ‘explain’ your own work. typically, that is less interesting.

TK: I find that one of the most interesting themes in the film. it’s very rapid how that relationship shifts, and it’s directly linked to wider societal and technological shifts. for example, people who used to ask rem questions for media outlets used to be mostly older, kind of stuffy intellectuals who would ask very serious, long, verbose questions referencing classic texts or theories. now it’s often a millennial writing for a website and the questions often are pop culture questions as much as they are intellectual, and the word ‘like’ is often interspersed many times throughout the questions. the shift in culture has effected not only the media but the way the public interacts with him as well. it used to be at his lectures he would sign copies of his books, now people want to take selfies with him. one of my favorite shots in the film is where rem allows a girl to take a selfie with him, he doesn’t smile, he just briefly stops and then he keeps moving, yet afterwards she literally jumps with joy. I can imagine it’s a strange and maybe uncomfortable shift for him, but a rich theme for me to explore as a filmmaker.

japanese architect shohei shigematsu leads OMA’s new york office

DB: did the process of making REM allow you to learn anything new about each other and the way you both work?

RK: I did not interfere at all in tomas’ filmmaking – I ‘surrendered’ to all his intentions. I recommend such an experience to all parents; it was not so much that I discovered unknown sides of him, more that the ‘reversal’ of (assumed) authority created a very special, tender dynamic that itself was a revelation.

TK: it’s hard to define learning something ‘new’ about someone you know so well, but I did get a better sense of how the pieces all fit together. I, like many people, used to view rem’s research projects and building projects as being separate. what I became viscerally aware of making, and particularly editing the film was that everything is inextricably linked, partly because I was literally making connections through my editing. a visit to the nothingness of the desert might spark a new thought that then becomes a research project that then informs a whole new focus on a new geographical region that then is translated into built projects that occur in that new area, the development of which are informed by breakthroughs uncovered by the research projects.

rem koolhaas in conversation at maison à bordeaux in france

DB: how conscious were you about making a documentary from a first person perspective? what were the reasons behind this, and in what ways did that visual narrative of the film develop over time?

TK: the first person perspective is one of the most important stylistic choices I made in the film. there were a few reasons I made that choice. firstly I think first person is much more evocative, immediate and engaging for the viewer, also in terms of visual style, camera angles, editing etc it allows for a much more interesting choice of shots and edits — to be inside the action rather than a detached observer of the action. it allows you to get physically closer but also in a more philosophical sense, you can get inside of the heads of the characters, rather than following the narrator, or seeing the narrator’s perspective.

REM is available on various formats in the netherlands, US, and UK from may 1, 2018

TK (continued): but maybe the most important reason was that I am really sick of the way most documentaries are made and feel. that’s primarily because they stick to prescribed genre conventions. some of which is for good reason, some of which is just kind of a remnant of an old way of doing things that hasn’t been questioned. for example, my film doesn’t have an extraneous narrator, you hear the different characters voices directly. I’m not in the film, no one is guiding the viewer, telling them what to think. that approach helps the film seem so much more immediate because you’ve removed a layer of separation between the viewer and the characters and ideas. I didn’t want the film to be didactic, I didn’t want anyone mediating the message for the viewer. I wanted them to get inside the heads of rem and the users and then make their own interpretations and connections in a kind of unburdened way.

architecture interviews (267)

OMA / rem koolhaas (338)

PRODUCT LIBRARY

a diverse digital database that acts as a valuable guide in gaining insight and information about a product directly from the manufacturer, and serves as a rich reference point in developing a project or scheme.