on the occasion of the venice architecture biennale 2021, the united arab emirates pavilion presents a large-scale prototype structure created from an environmentally friendly cement made from recycled industrial waste brine. knowing that portland cement accounts for 36% of all emissions related to construction activities and 8% of total anthropogenic CO2 emissions, curators wael al awar and kenichi teramoto showcase a research which explores how salt and mineral compounds found in the UAE’s sabkha (salt flats) could act in the development of renewable building materials.

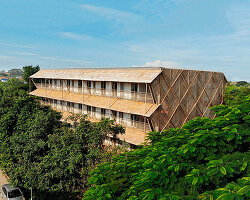

dubbed wetland, the pavilion displays a salt-based prototype measuring 2.7 meters tall and 7 meters by 5 meters wide on its exterior, creating a walkable interior space the size of an average 2x5m x 5m room. the structure is formed by 3000 modules made of an MgO-based cement designed by the curators in a collaborative process.

designboom met with wael al awar at the united arab wetland pavilion at the venice architecture biennale 2021 where he discussed in depth the development of the project. read our interview below.

images courtesy of the united arab emirates pavilion

DESIGNBOOM (db): how does the pavilion address this year’s biennale theme ‘how will we live together’?

WAEL AL AWAR (WAA): we wanted to address the climate urgency and our relationship as humans with planet earth and what is the responsibility and the role of the architect and the construction industry. I believe the 20th century architect did not care, to put it bluntly, and would say, I am an architect, I am a designer and climate change is part of environmental science or something that should be solved by others.

we cannot continue using the materials when we are aware of what their impact is on the environment. similarly, we cannot build in environments when we know there is social injustice towards the workers or builders of that context. in that sense, cement is a material that needs to be re-questioned. cement is responsible for 8% of global co2 emission, and we are a growing population. today we are 7.9 billion and it’s projected we will grow to 10.1 billion by 2060.

in 2019, the bill and melinda gates foundation issued a report stating that we will have to build the equivalent of one new york city every month for the next 40 years, to be able to house all of these new people. the question is, how do we do it? it is impossible today to think that we can do it using portland cement. portland cement has an impending ratio of one to one – to produce one tonne of cement you create one tonne of co2. the problem is therefore found in the chemistry and the answer has to be in geology. because the problem is the conversion of limestone to lime and the emissions of co2 it produces. lime is the binder or the glue in cement. so cement is a mix of sand, gravel, water, and the glue which is lime. finding an alternative glue would solve the problem.

DB: where did you start looking for alternatives to this binding material?

WAA: we started looking at the local geography, trying to see what could work as a glue other than lime. we stumbled upon the salt flats of the UAE, and we were fascinated by the crystal layers. when the salt crystallizes, it becomes strong, meaning that there is a binder. and once we started investigating further, we understood and learned that, for example, siwa, which is in egypt, is all built from karshif, a mix between salt and mud in their vernacular architecture. we learned from this that the binding material or mineral is MgO, it’s magnesium oxide. so, that is the glue.

DB: where can you source the glue?

WAA: we discovered that the best place in which we can source MgO is the reject block drying of desalination water. so then we extract the MgO from the desalination water process and use it to create this cement. the cement blocks you see here are all produced locally in venice. in fact, this cement we have created needs to absorb co2 actually to gain a structural strength to dry them. if it doesn’t absorb co2, it results in a very weak material. so in a way, it becomes a material that doesn’t create co2 emissions, and contrary to that, it absorbs them.

DB: how did you decide the form of the building blocks?

the building blocks can be done in bricks, can be done in slabs. but if we first questioned cement, we had to question the modern process of producing architecture too. we needed to question standardization, globalization, because modern architectures faces tremendous challenges against culture identity. how do you keep that or retain that in architecture? vernacular architecture was produced from materials found in nature — you found the wood, you worked with that wood. there was a certain connection between the architect or the builder and the material. I think in modern architecture that was completely lost. the architect and the material became so distant from one another: I can draw a design, send it anywhere in the world, and have it be built without me having to go there. but we have to question that process again and see if that is the right way moving forward.

WAA (continues): we were inspired by the vernacular architecture of the UAE which is made from corals. we drew coral shapes into sand molds and cast them with concrete. then these shapes are drawn by the builders themselves. we have four different types, with two different sizes each, so eight modules. this is again just for efficiency, speed, scale. it can be done in many more modules and types. so this becomes the antithesis of modern architecture. there is no drawing for this product. we have a guideline for the contractor, our process method, but I don’t have an architecture drawing with precise dimensions. we have a guide book, meaning that each culture can introduce their own identity or understanding into that guidebook. the production of this material anywhere in the world will always look different. this building block we have here in venice looks random, and chaotic, but actually it’s scientifically well studied.

DB: what is the current state of the project?

WAA: there’s still has a lot of research that needs to be done. this is three years worth of research. but still, because it needs carbonation, we’re only able to produce it as precast units, because cast in situ system becomes very hard to carbonate. and then you have the challenge of reinforcement. because you cannot reinforce with steel, because it’s assault based concrete. it just needs more research development, finding other ways to reinforce it, and maybe introduce the co2 molecule in the cast in-situ process chemically, to give it that enforcement.

pavilion info:

name: wetland exhibition research contributors

research team: wael al awar and kenichi teramoto, research directors; ryuji kamon, head of research and lab prototyping; lujaine rizk, lab and research coordinator; aisha al sahlawi, lab and research assistant; dina al khatib, lab documentation; ibrahim khamis, lab assistant; ahmad beydoun, lab assistant: adomas zeineldin, lab assistant; ibrahim ibrahim, lab assistant; alserkal avenue, dubai, lab space

collaborators: new york university, abu dhabi, amber lab; dr kemal celik, assistant professor of civil and urban engineering; dr rotana hay, research scientist; dr abdullah khalil, postdoctoral associate; dr ghanim kashwani, postdoctoral associate; cornelius otchere, student assistant; sara alanis, student assistant; roshan poudel, student assistant; university of tokyo, sato lab and obuchi lab; jun sato, structural designer; yusuke obuchi, digital fabrication designer; mika araki, structural designer; american university of sharjah, department of biology, chemistry and environmental sciences; dr lucia pappalardo, associate professor of chemistry; aysha shabnam, research and lab assistant

architecture interviews (267)

concrete architecture and design (723)

venice architecture biennale 2021 (76)

PRODUCT LIBRARY

a diverse digital database that acts as a valuable guide in gaining insight and information about a product directly from the manufacturer, and serves as a rich reference point in developing a project or scheme.