STREET FOOD STALLS STRIPPED OF COLOR IN MEXICO CITY CENTER

Earlier this year, the mayor of Mexico City’s Cuauhtemoc borough decided to ban the colorful, hand-painted signs that adorned thousands of street food stalls and give the urban landscape ‘a distinctive, authentically Mexican look for decades.’ This decision has left many local residents, street vendors and rótulistas (the commercial artists that paint the graphics on the food stalls by hand) feeling like the city’s cultural identity is forcefully fading in ‘a racist and classist erasure’, writer and photographer Kurt Hollander shares with designboom.

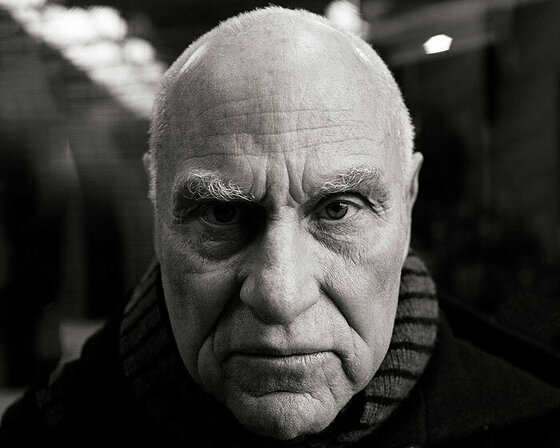

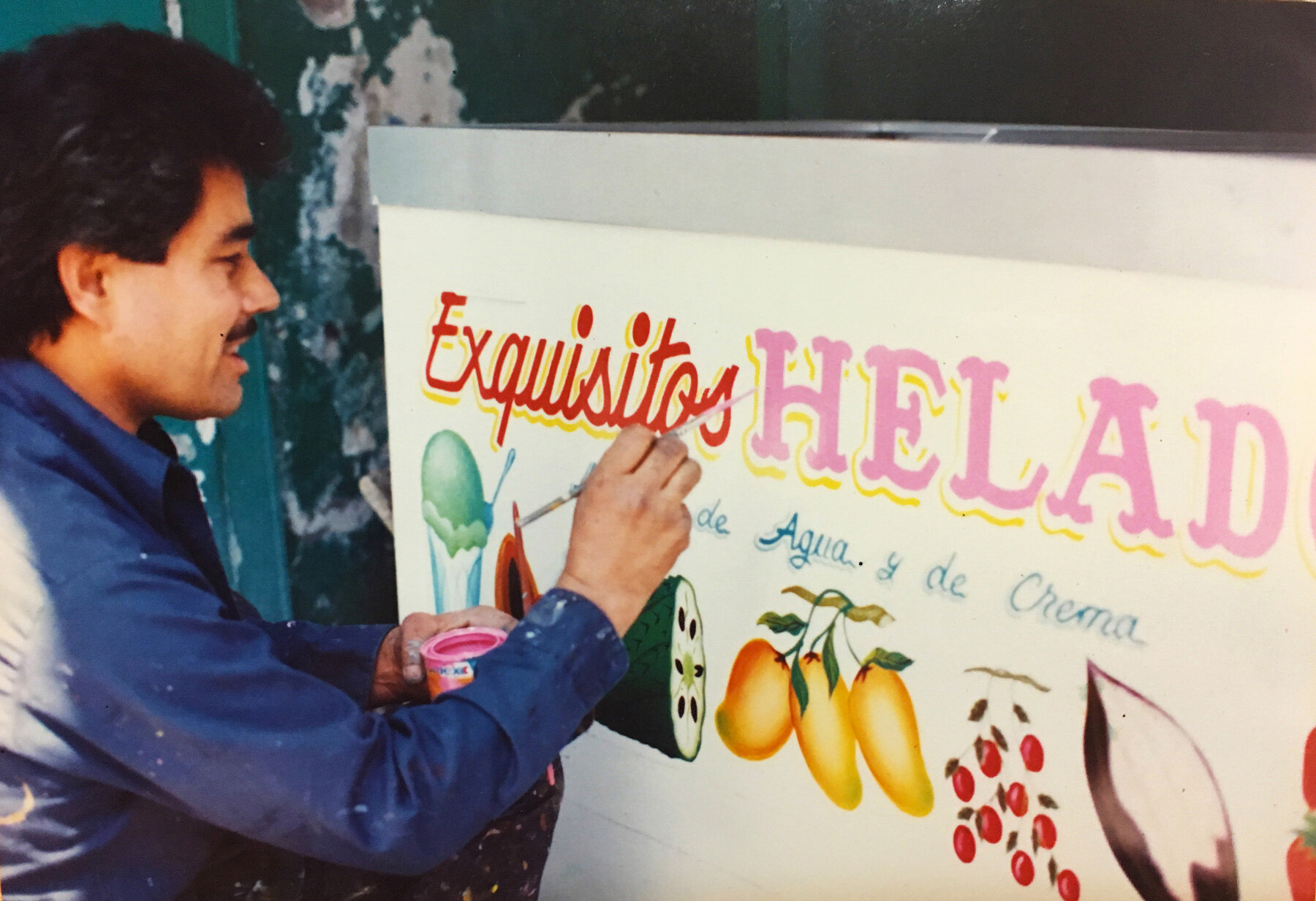

Originally from New York City, Hollander lived in Mexico City for over 20 years and since 2013 divides his time between Mexico City and Cali, Colombia. In the essay below, which has been adapted from his upcoming autobiographical book, ‘From Downtown to El Centro’, Hollander shares a brief history of the rótulos, his view on the borough’s recent decision and its impact on the local community. Read the full text below, along with images of the street signs taken by Mario Pérez, a painter and photographer from South Texas. For the past couple of decades, Pérez has been documenting the work of rótulistas on both sides of the border, especially the delegación Cuauhtemoc in Mexico City.

all images by Mario Pérez

‘THE PAINTINGS ON THE STALL’ by Kurt Hollander

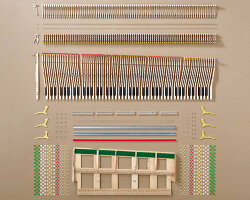

Mexico City’s delegación Cuauhtemóc, the city’s most commercial and tourist-friendly area, which includes the centro histórico and the ‘trendy,’ gringo-infested colonias Condesa and Roma, has just banned all rótulos. Rótulos, the hand-painted images and text that have given local markets, small shops and street food stalls a distinctive, authentically Mexican look for decades, can be seen as a continuation of pre-Hispanic glyphs and revolutionary graphic artists.

When I moved down from New York City to Mexico City in 1989, local comics and lurid pulp magazines had print-runs many times larger than any glossy magazine, the beer and cigarettes were still Mexican, local markets sold more food than Walmart, while quesadillas, tortas, esquites and other indigenous delights cooked on the street still outsold Domino’s pizza and McDonald’s burgers. The graphic designs and images used to advertise the local products were still painted by hand by commercial artists known as rótulistas.

In my early years living in Mexico City, I was surprised to see that upper and middle-class chilangos mostly looked down upon popular design (and the products and foods it advertised), in part because it was an element associated with the visual landscape of lower-class neighborhoods. For middle and upper-class Mexicans, popular working-class design, such as the posters for lucha libre and tropical music groups, as well as the hand-painted signs for small shops and, especially, street food stalls, was considered naco. The term naco has been defined as an Indian in the city (the word probably is the diminutive of Totonaco, an earlier indigenous nation in Central Mexico), but it is also the Indian in the city who has acquired the means to flaunt their new-found, flashy style. The term naco is also used by the upper classes to describe the bright, flashy commercial expressions of graphics and images in public spaces in Mexico that advertise cheap, glitzy products.

In 2007, I put together and published the book El Super, a collection of Mexican consumer products. Although many of these products were sold in packaging that is less-than-environmentally friendly, displayed images that were neither politically nor gender correct, and used ingredients that are banned in certain developed countries, working class Mexican consumers nonetheless adopted these products as their own and saw themselves reflected in the images on the labels, often of pre-Hispanic culture. El Super was an attempt to document images which, when assembled together, form a much truer cultural identity than any official or tourist-friendly version, an identity that even back then was in danger of extinction.

Over the next decade or so, as the North American Free Trade Agreement (NAFTA) began to decimate Mexico’s food autonomy by dumping thousands of tons of junk food and industrially-processed food products into the markets and restaurants of the city. Most of the Mexican products featured in my book have either been discontinued or, as is the case of the beers and cigarettes, are now the property of multinationals, their logos and images redesigned by foreigners with computer-generated images and typography. The rótulistas who paint the names of the food stalls and design seductive images of the food sold in white tin stalls located on sidewalks, work with the same aesthetic and techniques, but breathe life into them painting by them hand.

Naco is the Mexican equivalent of white trash in the United States and elicits the same response from the cultured classes. Naco is the cultural opposite of the bourgeois notion of good taste. Good taste is very important for the local Mexican cultural elite, as their self-image depends on how their lives compare to that of Europeans and other cultured cosmopolitans. The class struggle is often between people of good taste and people who like cheap food products that taste good. Just as many in the upper classes renounce any blood ties to ancient American cultures, so too naco is an aesthetic that the upper classes, who believe they are inhabitants of a modern, cosmopolitan city, cringe at when associated with Mexico.

In fact, however, upon closer inspection, naco turns out to be everything that is authentically Mexican. Mexico City, unlike major cities in the United States and Europe, is still a mostly working-class country with roots in indigenous culture, and globalized food and images have not yet come to dominate all cultural and social representations in the city. Hand-painted images and texts on the streets of New York City were for a long time the signs of immigrant neighborhoods, created by waves of immigration from Latin America, Europe and Asia, but they began to fade away when I was growing up there, leaving the city without its own authentic aesthetic.

In the late 80s the Mexico City rock group Botellita de Jerez first proclaimed naco es chido (naco is cool), while in the 90s the hippest tee-shirt brand in the city was named Naco and national and international artists in the city not only copied the aesthetic of rótulistas but also hired them to produce their work. These days, however, it seems these working-class commercial artists have fallen out of favor and their images of local food and culture are now seen merely as an eyesore by modernizing (read globalizing) forces in the city. The city’s government’s whitewashing of the city’s public image, which in no way improves health or hygiene, is obviously just a racist and classist erasure of naco imagery in favor of foreign tourists and upper-class Mexicans, the very people who would never eat street food in the delegación Cuauhtemóc for fear of Moctezuma’s revenge.

a rótulista on the street, 1994

Kurt Hollander is originally from downtown New York City but lived in Mexico City for over 20 years. He is a writer and photographer, author of Several Ways to Die in Mexico City (Feral House, 2013). His book of autobiographical essays, From Downtown to El Centro, from which this text was adapted, will be published in Spanish by Turner Libros this year with the title Desde las entrañas.

Mario Pérez is a painter and photographer from South Texas. For the past couple of decades he has been documenting the work of rótulistas on both sides of the border, especially the delegación Cuautemóc in Mexico City.

project info:

text: Kurt Hollander

photography: Mario Pérez

PHOTOGRAPHY (372)

PRODUCT LIBRARY

a diverse digital database that acts as a valuable guide in gaining insight and information about a product directly from the manufacturer, and serves as a rich reference point in developing a project or scheme.