since the founding of his studio in 1995, olafur eliasson has engaged audiences across the globe with an extensive and important body of work spanning sculpture, painting, photography, film, and installation. the danish/icelandic artist has set his monumental projects both in and around civic space and within museum institutions, each embodying his interests in perception, movement, experience, and feelings of self.

his urban artworks like ‘your rainbow panorama‘ — a 150-metre circular, colored-glass walkway situated on top of aros museum in aarhus, denmark — and more recently ‘ice watch‘ — which has seen 100 tonnes of inland ice relocated onto the danish city streets — seek a participatory dialogue with pedestrians and passers-by, offering an audience outside of institutions to engage with his creative undertakings. within museums, various sites from the louisiana museum of modern art to paris’ fondation louis vuitton change the ways in which viewers experience art and the architecture it is set within, relayed through works like ‘riverbed‘ — a giant landscape which unfolds throughout the south wing of the gallery — and ‘contact‘ — a light phenomenon which passes along the circumference of an open gallery space.

with a catalog of work that roots itself within significant societal interests, and a study of geometry that has informed his work for decades, designboom speaks to eliasson about his ongoing interest in all things circular and spherical, and his artistic thinking that challenges the way people perceive culture, community, and climate change.

olafur eliasson, ‘contact’, 2014

all images courtesy of studio olafur eliasson / image © iwan baan

designboom: what originally made you want to become an artist?

olafur eliasson: my father was an artist as well as a cook on a fishing boat, so I grew up with his artworks and lots of art books. funnily enough, my first physical introduction to the kind of thinking that goes into art making actually came through breakdancing. I started dancing in my early teens, and I became very obsessed with the awareness that dancing gives you of your body and space.

map for unthought thoughts, 2014, a film by SHIMURAbros, fondation louis vuitton, paris

video courtesy of studio olafur eliasson

DB: who, or what, has been the biggest influence on your work to date?

OE: having an artist for a father; my mother, who organized drawing lessons for me with an artist; robert rauschenberg’s goat with a tyre (monogram, 1955–59); the fall of the berlin wall in 1989; seeing claude monet’s water lilies (1914–26) at moma; the james turrell skyspace at moma ps1, new york (meeting, 1986); west coast light and space artists, such as robert irwin; reading a thousand plateaus, by gilles deleuze and felix guattari, in the early nineties; gordon matta-clark’s cutting in half of a house (splitting, 1974); the quicksilver-like policeman in terminator 2; the berlin art scene from 1994 to 1999; francisco varela’s brilliant book ethical know-how: action, wisdom, and cognition; the efforts being made by tania singer, director of the department of social neuroscience at the max-planck-institute in leipzig, to change the world through compassion; my studio team; and, hopefully, the global success of cop21 in paris.

‘riverbed’, 2014, installation shot

photo by anders sune berg, courtesy of the louisiana museum of modern art

DB: what are the differences between setting your work within institutions in comparison to the public space?

OE: in a museum, the framework is clearly present. museums offer structures and communications that affect how viewers experience art. I don’t necessarily go against the signature of the museum, but I do try to make it explicit. I’d like people to become aware that the museum is also a construct, that the artworks and experiences are relative to the users and to how the space is programmed. exhibiting in public space always entails working in a participatory way, but I actually don’t really distinguish between the two; public spaces also have their own regulatory premises, their hidden or visible ideologies, and the museum is very much part of the world – entering a museum may even make you come closer to the world.

eliasson and geologist minik rosing have made a visually striking contribution to the climate debate with ‘ice watch’

photo by group greenland

DB: what are you currently interested in and how does it feed into your creative thinking?

OE: art and creativity have much to offer the world outside the arts. artistic thinking is based on constant awareness of potentiality – of the idea that reality is malleable, relative, and that, through my actions, I can affect and change the world. art can touch people deeply; experience isn’t just in the head, it’s embodied. I’m speaking with more and more people who understand the scope of what art can do; people from the EU, from various corners of the UN, people working in remote parts of ethiopia, nepal. . . . even in davos, at the world economic forum, the arts are slowly leaving the entertainment side program and taking up a more prominent role. people are realizing that climate change and energy inequality, for instance, can be addressed with some force through art. and I’ve grown passionate about these topics. in 2012, I created ‘little sun‘, the solar-powered lamp and social business, together with frederik ottesen, and, last october, I did the intervention ‘ice watch’ in copenhagen, which marked the publication of the UN IPCC’s fifth annual assessment report on climate change.

DB: in what ways does ‘ice watch‘ build upon themes of global and environmental issues you have explored in your earlier pieces?

OE: interestingly, when I did ‘the weather project’ at tate modern back in 2003, climate change wasn’t on anyone’s agenda. at the time, the work was received as being about the museum as a stage, about sociality, embodiment, being singular plural. only later did people start thinking about it in relation to the climate – and I think that’s just fine. the work is open to this shift in attention. it welcomes it. even when I did ‘your waste of time’ in 2006, which anticipated ‘ice watch’ in some respects, climate change wasn’t really on the global agenda. it was also not what drove me to bring chunks of hundreds-of-years-old icelandic ice into an art gallery for visitors to touch them. the focus then was on direct, visceral experience – which has long been central to my art practice.

from this, I realized that encountering old ice may have extraordinary effects, and in 2014 I did ‘ice watch’ in city hall square in copenhagen with minik rosing, a geologist and great friend. when you touch an old block of melting greenlandic inland ice, you physically feel the reality of time passing and climate change in a way different to reading the newspaper or through numbers and scientific data. this is where the arts speak a strong, direct language. in two minutes, ‘ice watch’ can communicate more than can be said in 700 pages of a scientific report.

‘little sun’, 2012

detail of an image © merklit mersha, 2012

‘little sun’, 2012

image © michael tsegaye, 2012

‘panoramic awareness pavilion’, 2013

photo courtesy rich sanders

DB: what drives your continued study of spheres?

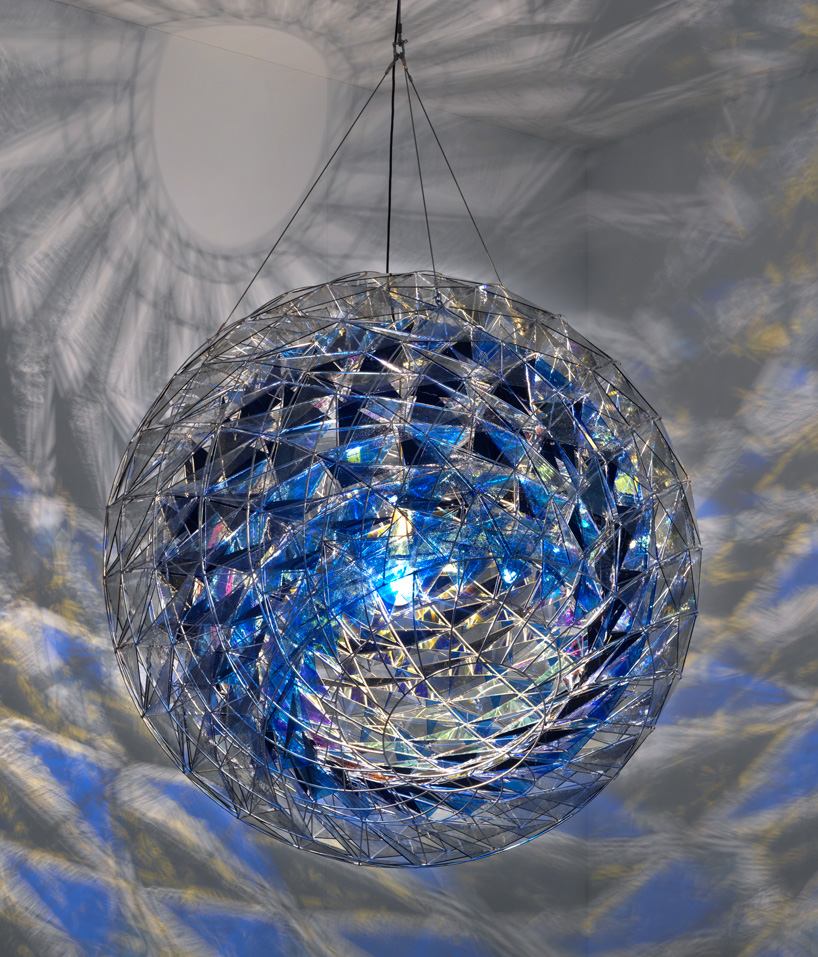

OE: I’m fascinated by geometry and partial to all things circular and spherical. they have this powerful, almost cosmic dimension. most of my earlier spheres are, in fact, complex polyhedra. to develop these forms, I collaborated for many years with the icelandic geometer and architect einar thorsteinn.

I like to think of the spheres as models for planets. I’m interested in the fact that our recent move towards the anthropocene – towards acknowledging, that is, the impact of human activity on the ecological systems and atmospheres that surround us – has shifted our relationship to all things planetary. we no longer look at the earth from a distance from a disembodied, google earth perspective: we know that we are inseparable from it. as bruno latour says: there’s no outside. we are inevitably caught up in the world and our actions have consequences for it, its atmosphere, climate. . . . the spheres are about looking at the world and at yourself at one and the same time.

‘lamp for urban movement’, 2011

stainless steel, colour-effect filter glass (cyan, yellow), black glass, aluminium, bulb / ø 180 cm

installation view at pinchukartcentre, kiev, 2011

photo by studio olafur eliasson / pinchukartcentre collection, kiev /© 2011 olafur eliasson

DB: based on their geometrical properties, what optical and sensory effects do the spheres generate for an observer?

OE: let’s say that the spheres are machines that create space, they space. some of them contain a light source inside that projects fragmented light out into the space where they are hanging, like a map projection. so it is not only, or primarily, the physical object in the space that interests me, but the way the light and the shadows and the colors claim and create space together. they perform architecture, you might say. a recent example is my ‘dust particle’, 2014, now installed in an atrium at fondation louis vuitton in paris as part of my exhibition ‘contact’. the particle is illuminated by sunlight that is projected into the building by a sun-tracking device placed on the roof, and it reflects the gehry building in such intricate ways as to make looking at it a very kaleidoscopic experience.

‘compassion sphere’, 2011

stainless steel, aluminium, paint, green quarz, coloured glass (yellow), colour-effect filter glass (purple), bulb, cable / ø 168 cm

installation view at studio olafur eliasson, 2011

photo by studio olafur eliasson / © 2011 olafur eliasson

‘compassion sphere’, 2011 (detail)

photo by studio olafur eliasson / © 2011 olafur eliasson

‘cold wind sphere’, 2012

stainless steel, coloured glass (dark blue, blue and light grey), mirror, colour-effect filter glass (blue), bulb / ø 170 cm

photo by jens ziehe, don de la clarence westbury foundation / © 2012 olafur eliasson

DB: in regards to site-specificity, how were you influenced by gehry’s architecture in the creation of ‘inside the horizon’?

OE: inside the horizon is a permanent installation located in a long passageway just outside the museum. the work is a viewing machine that affords a kaleidoscopic view of gehry’s building, and of the visitors within the building and moving about the installation. it consists of forty-three columns organized in the shape of a fresnel lamp, and it can be viewed from various vantage points. on the one hand, when you move around it, it is quite disorienting to catch glimpses of people who are somewhere else entirely. the view shifts with every step you take and changes in a kind of hide-and-seek, remixing gehry’s building, in a sense. on the other hand, there is one position from which the viewer sees himself in all the mirrors, reflected forty-three times. when you find this position, the work becomes a horizon and you are dispersed across its full length. it becomes a magnifying glass that shows you a bigger reality than what the individual reflections evoke.

inside the horizon, 2014

photo fondation louis vuitton / iwan baan © studio olafur eliasson

DB: can you tell us about any upcoming projects that you are especially excited about?

OE: I have an important solo show opening at the modern art museum, gebre kristos desta center, in addis ababa, at the end of february. ethiopia is a country I have grown to know intimately over the years. in 2012 my institut für raumexperimente (institute of spatial experiments), an experimental arts school, did a ten-week residency in addis. I have many friendships from that time – with the alle school of design and art, for instance, where I’m now an adjunct professor, and with the extraordinary artists at netsa art village. I’m looking forward to installing the show and meeting up with friends and collaborators in addis.

I am also thrilled to announce that we are launching amazing new solar-powered products from little sun this year. I’ll be posting the first prototypes on instagram soon.

OLAFUR ELIASSON (76)

PRODUCT LIBRARY

a diverse digital database that acts as a valuable guide in gaining insight and information about a product directly from the manufacturer, and serves as a rich reference point in developing a project or scheme.