absorbed by a growing tower of smoke, driver ‘nghamshi’ waves from the seat of his BMW 325i, of which the engine is revved to a deafening max. on a makeshift lot, occupied by dozens of modified cars, young men like him claim the pitch with tire marks tracing their dangerous stunts. this is the world of spinning, where success is measured by how far a driver is willing to go before the engine gives out. ‘you try to make something impossible happen in that small space‘, nghamshi explains, and he does so, to the response of screams and cheers from the surrounding crowds.

video still, courtesy of leo maguire

award-winning british filmmaker leo maguire was invited into this world five years ago after being approached to direct a short film documenting the cultural phenomenon. it’s a project that took him to soweto where spinning shares its roots with the people that live there and where he met ‘nghamshi’. there he learnt that spinning – a product of the ever-tightening apartheid regime in south africa during the 1980s – originally involved the appropriation of cars, status symbols of white supremacy. he heard stories of black africans performing stunts with them as an act of defiance, an act that quickly became both reaction and ritual in honor of activists who were killed.

nghamshi’s BMW 325i, image courtesy of leo maguire

spinning has since experienced an evolving definition, becoming the fastest growing motor sport in south africa with a new generation pushing to make it subculture mainstream. once shrouded in darkness, only synonymous with nighttime events held in secret, today it attracts crowds to race hubs across the country, offering youth a positive distraction from crime. it also attracts female spinners, like 21-year-old stacey-lee may and 27-year-old cleo quickfall, who have both experienced local and international acclaim. even white africans like dylan brough, who the videographer met and came to know as ‘vaatjie’, are getting involved in an activity originally born from the social disparity between races.

designboom came across spinning on a recent trip to cape town, where we met kufa makwavarara, a zimbabwean artist featured in the zeitz MOCAA exhibition, ‘five bhobh – painting at the end of an era (2018-2019)’. curated by tandazani dhlakama, the exhibition featured twenty-nine artists whose work was thought to have captured a moment in history characterized by anticipation, angst and hope. part of the body of work by the young makawavarara, his ‘spinner guluva’ illustrates spinning at grass-roots level reflecting on a 40-year-old act of defiance in one of the regions most popular mediums: present-day painting.

painting ‘spinner guluva’ by kufa makawavarara (2015), private collection, courtesy of the artist and collector

with the same appreciation, maguire describes spinning as a kind of performance art: ‘something beautiful’ born out of ‘something brutal and violent’. following the discovery of his short production entitled ‘soweto spinning’, designboom spoke to the filmmaker about the phenomenon and its evolution from subversive activity, to legal sport with recognized art status.

leo maguire (LB): I was approached by a production company to direct a short brand film for a well known spirits company. they had found the world of spinning in south africa and thought it would be something I would be attracted to. I went there for an initial research trip, and to meet with some of the drivers in the scene. what hit me first was how segregated south africa was, even after apartheid.

one sportsman jumps on the hood of a spinning car after driving it into a frenzy and jumping out of the vehicle

DB: over what time did you film? can you detail the location a little?

LM: the research trip was towards the end of 2013, around the time when mandela passed away, so it was a super interesting and emotional period to be there. I met with lots of spinners from different backgrounds and places in gauteng province. I decided to focus on one driver, ngamshi, who was an old school spinner, he had been around at the birth of it, and he had lived his entire life in soweto.

DB: how were you accepted by the community?

LM: I worked with south african filmmaker pule earm, who had a made a low budget drama about spinning. he was trying to establish his own organization and legitimize spinning as a sport. he wanted to create an academy to teach a new generation of spinners, as he felt that it was a positive way to keep youth away from crime. on my first trip there I was picked up from the airport by pule, we traveled to a township, and I spent the next 3 days meeting spinners and going to illegal night time events in and around various townships. I was the only white person I saw in those first three days. no white afrikaans would venture into these places due to a fear of violence, but I never encountered any animosity or difficulty. it was the opposite, I was welcomed, people couldn’t believe that a filmmaker from london was there to talk with them and experience spinning. eventually I did meet a white afrikaans spinner called vaaitjie, he would go to townships and spin, but he was unique.

DB: did you establish a relationship with the driver in the video? or any other drivers in the area?

LM: I made a real connection with these men. nghamshi was a very reserved man, and on first meeting he didn’t reveal much. after getting to know over 30 drivers, I came back to him and we spent some time talking. what emerged was this thoughtful and passionate man. he wasn’t brash or arrogant like some of the other spinners, he possessed real humility.

I also made some good connections with other characters from the scene, and after making the film, I returned to spend some time with them. I wanted to make a feature doc about this world, I felt it was a great landscape in which to explore masculinity and modern south africa, but I couldn’t get the funding to make it happen.

spinning still takes place illegally, out of the safety and control of official arenas

DB: the spinning has its routes in car appropriation, in which way has it developed since then?

LM: yes spinning has its roots in theft, but I think that’s a simplistic narrative, for the spinners it was about defiance. black and colored men would travel into the suburbs and take the most prized possession of the white afrikaans male, his BMW 325is. they would take this car/prize back to their segregated community and spin them in the streets for everyone to see. it was a huge ‘f*** you’, an act of defiance, a way to shift the balance of power, I always saw it as a form of performance art. out of something brutal and violent, something beautiful.

the world of spinning has now changed and it is a legitimate sport in south africa, drivers perform in stadiums for paying customers. it is now safer and slightly regulated, but I always found it a bit lacking. it didn’t have the energy and vitality I experienced at previous spinning events in the streets of townships. spinning would just light up a community, people would lose themselves, it was something special to witness.

DB: why in your opinion is there a fascination with the use of BMW models?

LM: the BMW 325is e30 was one of the greatest BMW’s ever made. it had aluminum body parts to make it a lighter car, and it was one of the most prized vehicles for a white afrikaans man to own. this made the car a target. today the cars are not stolen, they are prized vehicles that are lovingly looked after by their owners. nghamshi had owned his cherry red 325is for many years, he said he loved her as much as his wife! as the BMW’s are rear wheel drive, and have relatively small wheels they are easy to spin. they also have 50-50 weight distribution, so I presume they are easy to balance and control in a spin.

DB: were you able to understand the ins and outs of the sport, the tricks and the way in which each performance is measured?

LM: it is a very subjective thing, they now have technical courses to spin around and rounds are judged. at the illegal night events I witnessed, the aim of the game seemed to be to spin the car as close to a crowd as possible without injuring anyone, it was dangerous and terrifying, but also incredibly exhilarating. people would go wild, they would lose themselves and almost become possessed by the energy, excitement and danger. it reminded me of exorcisms in churches, where people seem to go into another dimension and communicate with spirits.

DB: when was the video first presented?

LM: never! at the very end, the spirits company’s legal department didn’t think it wise for an alcohol brand to align themselves with an activity involving motor vehicles, drink driving, so the film was never released, which I think was such a shame for nghamshi.

these young men and women are declared the ‘kings and queens of smoke’

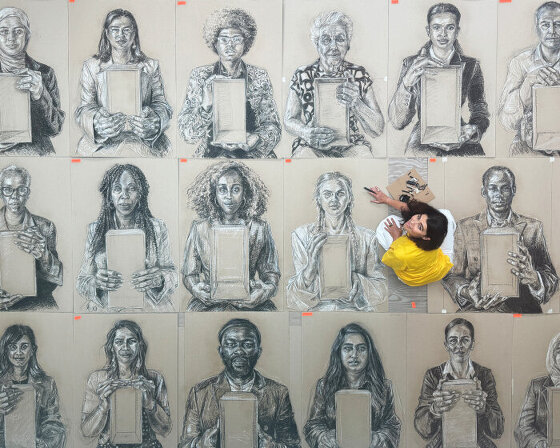

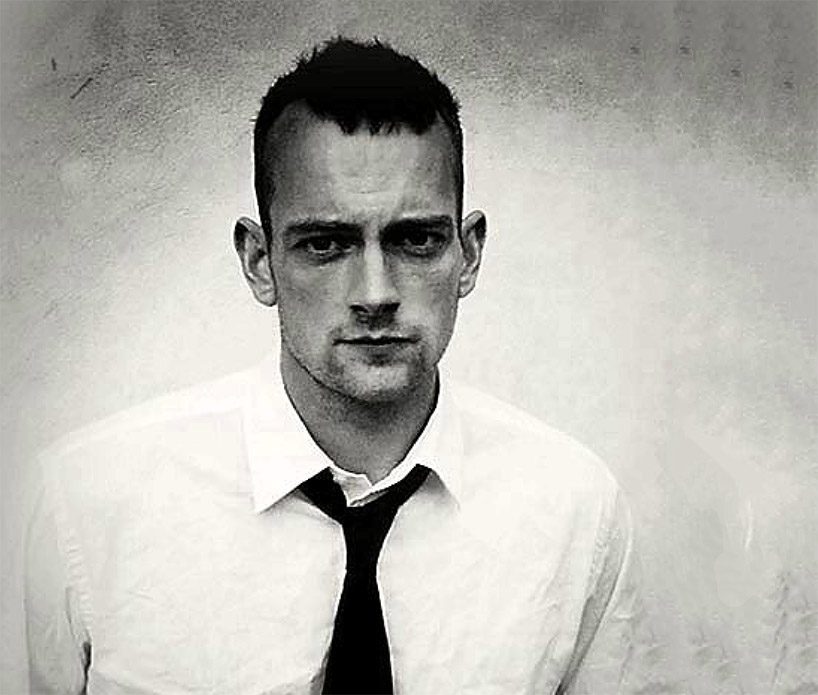

about the artist leo maguire

leo maguire (b1981 cornwall) is an award-winning british filmmaker, whose artistic practice includes photography, sculpture and film. he studied at the university of wales newport and stroud school of art. in his directorial debut film ‘gypsy blood’ (2012) he gained unprecedented access into the world of bare-knuckle fighters in britain’s traveller community. the film won best newcomer at the grierson awards and was bafta nominated. maguire’s work is concerned with the complexities of masculinity, identity and belonging.

about the painter kufa makwavarara

kufa makwavarara was born in zimbabwe. from 2001 to 2003 he studied at the national gallery school of visual art and design in harare, zimbabwe and currently lives and works in cape town, south africa. makwavarara began exhibiting with gallery delta, harare, in 2000, where he has been included in exhibitions such as from sound to form (2013) and roots (2010). other exhibitions include frieze at rk contemporary, cape town (south africa: 2018); dialogues at state of the art gallery, cape town (south africa: 2017); and emergence at ebony curated, cape town (south africa: 2014-2015).

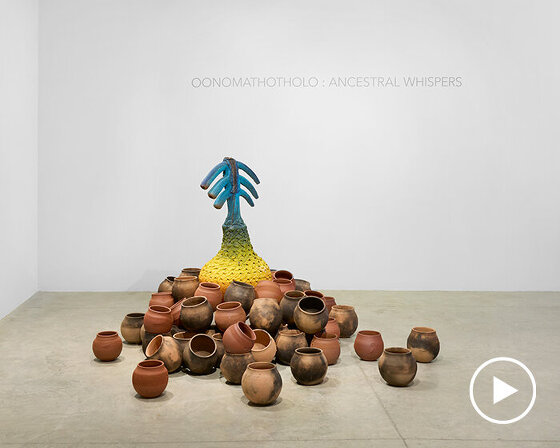

about zeitz MOCAA and BMW’s arts and cultures

housed in the historic grain silo complex in cape town, the zeitz MOCAA is the world’s largest museum dedicated to contemporary art from africa. completed in 2017 and designed by heatherwick studio, based in london. as part of its long-term commitment to contemporary and modern art, BMW South Africa is partner of the zeitz museum of contemporary african art (zeitz MOCAA). in 2018, kufa makwavarara has been one of three artists in residence of zeitz MOCAA, taking part in the BMW art talk ‘five bhobh: painting in parables‘, moderated by doreen sibanda, executive director of the national gallery of zimbabwe, in conversation with the other artists in residence, misheck masamvu, and richard mudariki.

automotive curiosity (304)

BMW (286)

zeitz MOCAA (9)

PRODUCT LIBRARY

a diverse digital database that acts as a valuable guide in gaining insight and information about a product directly from the manufacturer, and serves as a rich reference point in developing a project or scheme.