Building biospheres with microclimates by bas smets

Bas Smets and Stefano Mancuso curate the exhibition Building Biospheres at the Belgian Pavilion, a controlled microclimate with more than 400 plants demonstrating plants as smart living beings. Shown during the Venice Architecture Biennale 2025 at the Giardini, the artificial climate looks into the effects of plant intelligence and biospheres in architecture, both for recent and historic buildings. The exhibition runs at the Giardini di Biennale between May 10th and November 23rd, 2025. Before the opening, Bas Smets spoke with designboom about the exhibition he conceived with the neurobiologist Stefano Mancuso. ‘I think the moment we can tap into the logic of plants, we can have a much faster, more intelligent, and more sensible way of thinking about the city,’ he tells us.

Greenery thrives around the biosphere prototype. It shows the kind of future Bas Smets has in mind, one where the plants and trees are the natural sensors to the environment. They detect what they need on their own and supply people with what we need in order to survive: cleaner air, cooler areas, healthier state of mind. In this utopic, plant-filled biosphere Bas Smets imagines, fuse-like boxes cling onto the growing plants, monitoring their state and health. Tubes go through the entire landscape, pumping water as soon as the sensors detect the plants need them. Then, above the greenery and just below the skylight, artificial LED lighting switches on and off and can change its warmth, acting as the sunlight in the biosphere brimming with plants.

all images courtesy of Bureau Bas Smets, Stefano Mancuso, Flanders Architecture Institute | photos by Michiel De Cleene

Plant intelligence at the belgian pavilion in venice biennale

The prototype Bas Smets and Stefano Mancuso bring to the Venice Architecture Biennale 2025 hints at their ongoing research in developing plant-filled biospheres and microclimates. The smart monitoring system gathers data based on the behavior of the plants and activates the necessary means to keep them from withering.

The artificial lights turn on, water streams, and air flows. It’s the technology that tends to the landscape, with the humans acting more in the backstage, maintaining the system’s health instead of the plants. Between October 2024 and March 2025, the landscape architect and neurobiologist worked with plant ecophysiologist Kathy Steppe of Ghent University and software developer Dirk De Pauw of Plant AnalytiX for the installation.

Bas Smets and Stefano Mancuso curate the plants-filled exhibition Building Biospheres

Interview with Bas Smets

The design team also invited other architects to help build the biospheres and controlled microclimate at the Belgian Pavilion. They include Lisa De Visscher, Petrus Kemme, Elmēs, Maud Gerard Goossens and Henri Uijtterhaegen, Panta, Lisa Mandelartz Schenk, and Steven Schenk. During our interview with Bas Smets, we asked him what plant in the exhibition had piqued his interest. He beckoned us to follow him and showed us the magnolia grandflora plant towering over the visitors as soon as they enter the exhibition.

A few days before the opening, the flowers of this plant bloomed, partly because of the biosphere Bas Smets and Stefano Manuso put into place. Visitors can now see them in their glory, peeking through the over 400 plants around the installation. The architect shares with us that the presence of the flowers is the confirmation that he’s in the right pursuit towards understanding plant intelligence through biospheres. We discuss this, among other things.

the prototype is a controlled microclimate with more than 400 plants

Designboom (DB): How do you define plant intelligence and its relationship with architecture? Is this a new or resurging theme?

Bas Smets (BS): Humans are animals. We think like animals. Understanding plant function is hard. What I’ve been doing for the last ten years in my discussions with neurobiologist Stefano Mancuso, is understanding plant intelligence in a better, more profound way and bringing that into my designs. I’ve done this, for example, in the Arles project in France with the LUMA Foundation, but also in Paris, which is an extension of La Défense, because with this better understanding of how plants function, you can make new landscapes. Here we bring it one step further. We bring plants inside the building and read the building as a microclimate.

We made climatic studies to understand below the roof lights what kind of climates it creates. And it creates a climate of the understory of the subtropical forest. The canopy of the leaves is here, of course, represented by the roof. The temperature is about 20 degrees Celsius. And so we brought more than 400 plants from the subtropics into the pavilion. We measure what these plants need. We have sap flow meters. And with that information, the plants themselves make it rain. They turn on the light when they need more light, and they turn ventilation when the humidity builds up too much. So it’s an autonomous system where the plants produce a microclimate indoors.

the artificial climate looks into the effects of plant intelligence and biospheres in architecture

DB: Are there any side effects to building artificial climate?

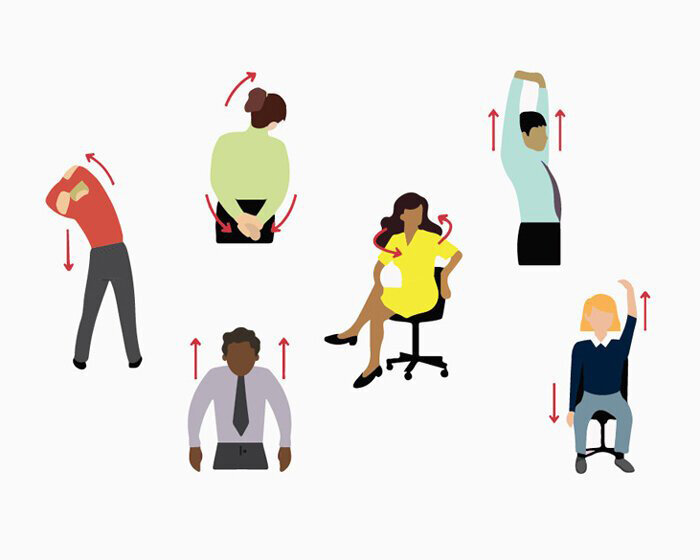

BS: The one difficulty is that the humidity builds up, and traditional walls don’t like humidity. That’s why we worked with architects, thinking, how could the architecture also change with this new relationship between buildings and plants. It’s about not thinking of a building as a single climate everywhere, which we do now. Now with thermostats, you set it at 21 degrees, and it’s 21 degrees everywhere. But maybe you want it warmer in the living room; you want it more humid in the bathroom. We should think of a building as different microclimates that plants can help produce.

DB: Can you explain some of the ways architecture or buildings can evolve into dynamic biospheres? Is this limited to recent or upcoming architecture, or can we also apply it to historic buildings?

BS: Architecture has always been about survival, right? We’ve been protecting ourselves from the rain, from the wind, from the snow. I think with the current climate crisis, architecture should again be about our survival, but also about plants and animals. In this new symbiosis between plants and buildings, we can come to a whole new way of understanding architecture. This can be done in a new building or in an existing building.

The adaptive reuse, which is now so important, could incorporate them. We worked with young Belgian architects to give an image to those ideas. For example, in the room here next to us, there are two studies. One of them is on an office building, and how it can produce its own air. Building biospheres in that can create a park for the residents. It can produce the fresh air that is unused or untapped in that architecture.

fuse-like boxes cling onto the growing plants, monitoring their state and health

DB: Can controlled-climate buildings be easily replicated? Do we currently have the right and enough resources to reproduce them?

BS: Right now, no. So, this is a prototype. It’s the first time that we’ve tested this. We’ve tested it already for six months in Ghent. Now we’re testing it for six months in Venice, and after those 12 months, we will make a report to see how we can adapt it, how we can use it in existing or new buildings. But it is really a prototype that we’re bringing the Venice and we’re still working on it. We’re still fine-tuning it. We’re still finding the balance between the natural intelligence of the plants, the artificial intelligence of the software, and all that in a collective intelligence, working with University of Ghent, with all of the scientists involved in the projects.

DB: What are the current experimental technologies that you’ve been trying or looking into to understand the intelligence, capacities, and life of plants?

BS: What’s interesting is you see on this tree to capture what the tree is thinking and what it’s doing. We need a lot of technology. I’m sure that this (he is pointing at the fuse-like box monitoring the plants’ health) in five years, ten years will be just a little box that you put on the tree, and the tree will emit all that information. So, I think we’re going from a very mechanical approach to a much more sophisticated approach to the future.

My dream, and I gave it a name, is what I call Urban Tree Network. It means to have every tree in the city as the most sensible sensor of the city. If you would connect all these trees, you would know immediately in real time what’s happening here without pollution, you would know the traffic and the routes, and they could sense the vibration. You would know when a branch is broken. So, I think the moment we can tap into the logic of plants, we can have a much faster, more intelligent, and more sensible way of thinking about the city.

Bas Smets | image © designboom

the exhibition runs at the Giardini di Biennale between May 10th and November 23rd, 2025

project info:

name: Building Biospheres

curator: Bas Smets | @bassmets

neurobiologist: Stefano Mancuso | @sonostefanomancuso

pavilion: Belgian Pavilion

teams: Lisa De Visscher, Petrus Kemme, Elmēs, Maud Gerard Goossens and Henri Uijtterhaegen, Panta, Lisa Mandelartz Schenk and Steven Schenk

event: Venice Architecture Biennale 2025 | @labiennale

location: Calle Giazzo, 30122 Venice, Italy

photography: Michiel De Cleene | @michieldecleene