designboom visits exil collective in beirut

For the past two years, Exil Collective has been actively promoting a new understanding of design in Lebanon and the Middle East. Established in the summer of 2020, amid extraordinary circumstances, the Beirut-based incubator is democratizing access to quality products through a set of guidelines ‘meant to optimize creation, production, and distribution of design objects imagined by local talents and produced by local artisans.’

The collective was founded by Tatiana Akl, Joseph Geagea, Antoine Guekjian, Youssef Bassil, and Rania Abillama, joined by Omar Bassil, an in-house designer. Fueling their vision is a talented pool of independent creatives working closely with Lebanese manufacturers and artisans to bring their concepts to life. ‘[We’re] making use of their ability in new and different ways to create objects meant to be produced and reproduced many times,’ writes the team. Together with its talented community –ranging from university students to established designers– Exil Collective has successfully nurtured a collaborative and inclusive ecosystem where alternative solutions lead the way to locally feasible, affordable, ethically made, and minimal-waste products. Each new creation is then proudly displayed on the incubator’s online shop.

designboom visited Exil Collective’s co-founders in Beirut, where a heartful conversation unfolded about steering their ambitious vision through Lebanon’s turbulent waters.

‘Ideal Platonique’ by Tatiana Akl | image © Giorgio Karam via Exil Collective

interview with the founding team

designboom (DB): What makes you stand out as an incubator in Lebanon is the set of guidelines you put together to help designers achieve affordable, feasible, and circular-based products. Could you walk us through these guidelines? Were there any challenges while setting them up?

Tatiana Akl (TA): The whole idea behind Exil started because of these guidelines. Youssef, Antoine, Omar, and myself were studying product design at the Académie Libanaise des Beaux-Arts (ALBA), and Joe studied Finance. We then graduated and realized that after working with Lebanese designers, most of them focused on creating bespoke furniture and products; they focused on collectible designs that were not really accessible to everyone. Their work wasn’t really selling anywhere because of the economic crisis and overall situation in Lebanon. And it was too expensive to produce; we realized we wanted to do something more accessible to everyone, especially our generation, people who were moving out or traveling, etc. So, this is why we put down this list of criteria. For example, one guideline states that the production cost can’t go over 80 dollars; it also depends on what the product is. Every object also has to be flat-packed and light for shipping purposes so that it doesn’t cost five times more than the product itself. This is one of the main issues in designing furniture. Once we came up with the list, we showed it to our designers that you see on our website, and they loved our idea. They don’t usually think this way; they just draw something and go and check how much it costs. What we’re doing is a reversed exercise.

Joseph Geagea (JG): And in terms of challenges, one of the main ones had to do with what material the designers would use. We had to educate some of them on what was available here in Lebanon for them to re-adapt their designs and to be able to produce something. There was a lot of back-and-forth teaching; that’s why we created a mentor-mentee relationship, especially between the younger designers and the more established ones that have joined our collective. For once, a discussion and teaching bond were unfolding between designers. For example, if one product was not exactly feasible, we either had our head of production (Antoine) or one of the more established designers give advice. From there, you could see the product evolving into one we’re more able to create.

at the studio | image © designboom

DB: Can you elaborate on how your guidelines help shape the designers’ creative process?

TA: Yes, so back in school, this was an exercise we had to engage in. It’s harder when you have no guidelines to follow because everything is open to you. So the more you give criteria to designers, the more they come up with solutions, actually.

Omar Bassil (OB): I can think of sand casting; that’s a specific production technique, and we used it to create a few products from our launch. We even got to go to the sand caster and see how it’s done. This allowed our designers to think up their products. Witnessing how a technique works, coupled with our guidelines, may seem limiting at first, but knowing what’s possible with each production method can also be inspiring. Some of our nicest products were made with our sand caster, who we work with regularly.

TA: It’s also an exercise for the designer to consider the material. Let’s say someone has an idea for a product made of brass; most people don’t really think about how heavy this material is and how much it costs. So they just go for it and end up paying 500$ to produce it before selling it for triple the price. Now, by replacing brass with other materials, coupled with the techniques available for designers to use, we’ve created an interesting challenge! We’re starting to promote more feasibility in Lebanon. We don’t have all the techniques and machinery available here, and that’s where our guidelines help.

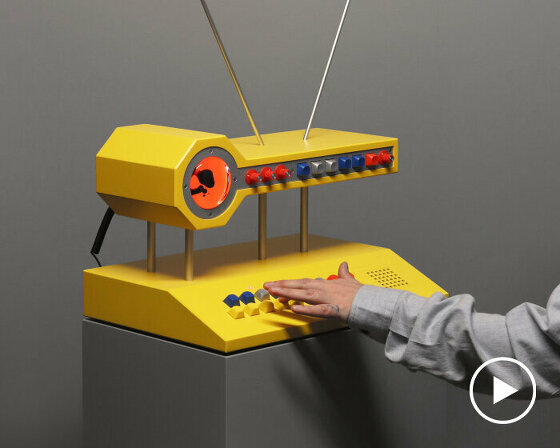

‘Notokay’ by Youssef Bassil | image by Exil Collective

DB: You founded the studio during the pandemic and, since then, have soldiered through the Beirut port blast and economic crisis in Lebanon. How has living through three consecutive, turbulent events impacted your work ethos and mindset as a collective?

JG: When we started during Covid, we did an open call to invite as many designers as possible. We described Exil to them, the idea behind it, and introduced the specification sheet. We started digitally; I was based in Switzerland, Tatiana was in Paris, and the rest of the team was in Beirut. Obviously, everything that happened here impacted us heavily; you can’t run a business here as you would in another country — from the registration process to simple things like invoicing the artisans — because everything operates in an unformatted, unofficial way. Antoine goes to an artisan and asks him for an invoice; the guy laughs and says he doesn’t need one. We live in a chaotic environment, but you have a lot of creativity from this chaos. One of the nicest things, too, is how this collective gathered designers in the same space to pursue the same goal: we can create something good if we set up an ecosystem together, an ecosystem that flourished out of the situation that we’re in. It was a very competitive environment before, and we’re trying as much as possible to promote a collaborative approach where we share resources and information. If you want, this is the silver lining out of all this chaos.

TA: We actually started right after the explosion. We had the idea in September 2020, and because of the circumstances and the crisis, all of these artisans began closing down, and most of them were not getting the help they needed after the explosion. One of the things we focused on was to continue producing here because many designers moved to Dubai or started producing in Italy. So when we approached the more established designers, asking them to give us a list of artisans, they were open to the idea because they knew that if we didn’t work with them, they were going to shut down. So in a way, this all stemmed from everything that happened in Lebanon.

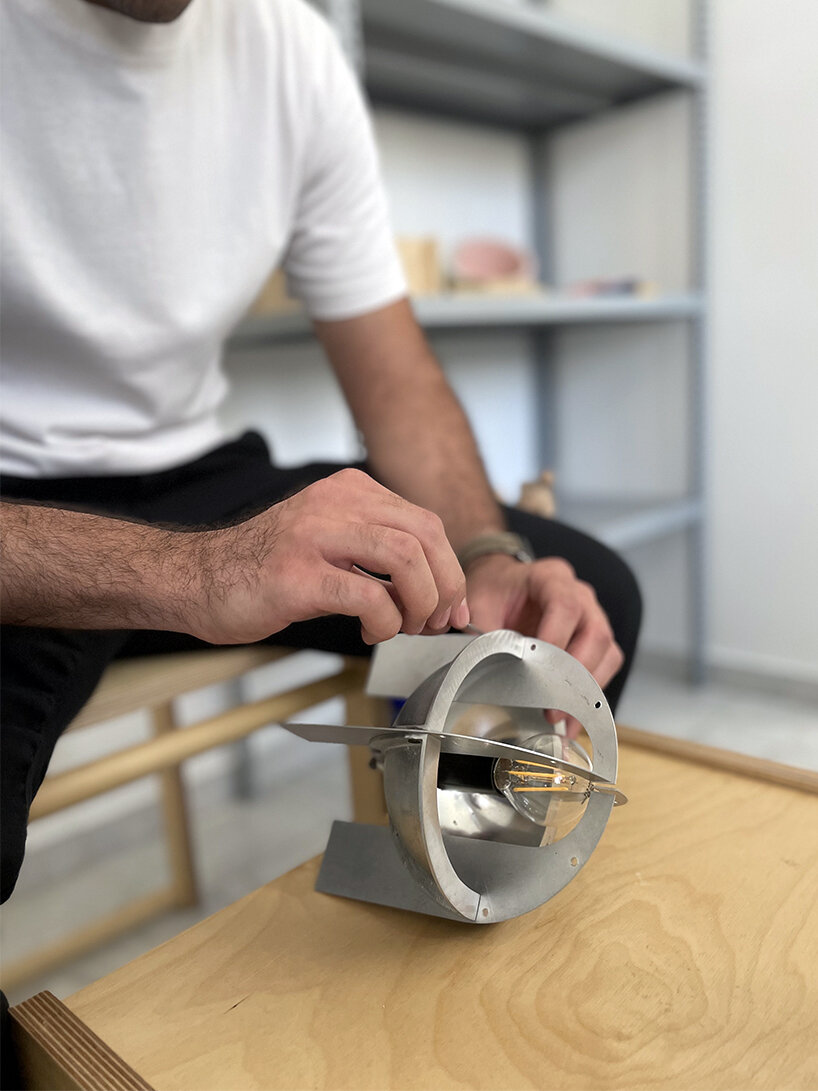

‘Sputnik 1’ by Antoine Guekjian | image © Aly Saab via Exil Collective

DB: Considering Lebanon’s turbulent circumstances, how does a typical day look like for the studio?

Antoine Guekjian (AG): We can start with last year when we launched a production line for an exhibition at Dubai Design Week. This was the most challenging part because we had more than 30 items to be produced in less than two months. We didn’t have fuel in Lebanon. There was also no gas for cars and no electricity. So, what we mainly did, other than designing and following the production, was to provide enough fuel for the artisans to turn on their generators and work on our products and have enough gas for our cars to move around. This is how we started last year, but we were glad things worked out. Our day-to-day now still looks a little like this. Aso, if the material is unavailable in Lebanon, but the designer wants to use it, we make sure they get it before we can proceed. So we design the other way around. We start from what’s available (the production, materials), and then we see what we can do with that availability.

TA: The production process, which is the bulk of our operation, is the most challenging part — especially here. Antoine and Omar are taking care of everything that has to do with this.

EC-01 chair and ES-01 stool | image by Exil Collective

DB: Besides ‘elevating local craft’, you also focus on creating user-friendly products like your EC-01 chair and ES-01 stool. What makes an object user-friendly for you?

OB: With the design process for the EC-01 chair, we wanted to work with the simplest means of production and the simplest way of assembly for it to be user-friendly. We had the flat-pack feature in mind for shipping and ease of use. What we like with these types of products is that they’re intuitive in how we build them. When you receive the chair disassembled, we want to make sure that it’s obvious where each piece will go; this was a critical part of the design process. How approachable, intuitive, and simple the object will be. Apart from that, we also focused on making something with a few pleasant visual elements using plywood, a raw material that’s nice to the touch. The lounge chair we’re launching at the Beirut Art Center is a continuation of that EC prototype. The idea was to use the same type of assembly and design language but for a more relaxed chair.

JG: Omar also thought about fitting both the chair and stool in the same box we use for shipping.

OB: Yes, and we also wanted to reduce as much waste as possible by using the most out of a single plywood board to design the chairs.

‘KEE’ side tables by Karel Kargodorian & Sacha Samaha | image via Exil Collective

DB: Speaking of the exhibition at the Beirut Art Center, ‘From The Rooftops’, can you walk us through the concept behind it?

TA: A local studio called BeirutMakers, led by Guillaume Credoz, does a yearly exhibition where they gather makers, architects, and designers to showcase their work. This year, the art center contacted Credoz, saying they wanted to occupy their rooftop with furniture that can stay there all year long — for people to gather, sit, and relax.

JG: Also, concerning the choice of title, which they came up with, you have a lot of rooftops in the city that are relatively unused or mostly occupied by generators, water tanks, etc. So the exhibition reimagines the functions of those rooftops as spaces where we can sit, gather, and even escape a bit of the chaos of Beirut.

DB: And going back to your craft, is there a particular production technique you find most interesting?

OB: I think sand casting; it’s a fascinating production method and is specific to this region. So it’s nice to harness the benefits and teachings of this ‘local’ method and shed some light on it. It’s pretty easy to understand the way of working it, and it’s very interesting to watch how it’s done as well.

‘Keep that cold to yourself’ by Architecture et Mécanismes | image by Exil Collective

DB: How do you approach the diversity of styles within the collective’s online shop?

JG: Although there are all of those restrictions set up, you can still see how diverse the creations of our different designers are — that’s because we want to promote that individual vision; if we like their product, they’re free to think about the choice of colors and so on.

TA: We want each product to reflect the designer’s identity. We didn’t want to restrict them in the aesthetics. But, of course, the collections have to be homogenous to some extent, and the objects have to go well together. When we feel that a product doesn’t work with our spectrum of how we see things, we fix it with the designer and think about it in another way. In the process, we also learn a lot about how each designer thinks, creates, and comes up with ideas.

Exil Collective’s prototypes at the Beirut Art Center | image © designboom

DB: Apart from the shop, you also developed an ‘open source production library’ with the local initiative The Ready Hand to put several Lebanese artisans on the map. Can you elaborate on that idea?

TA: We actually had this in mind since launching Exil. We were writing down all of the artisans we used to go to, the ones we currently and want to work with. Back in university, one of the main issues was finding the proper artisans for them not to charge us a lot as students. We didn’t have access to that knowledge. Even now, very few young designers have access to them. They don’t know who to choose or go to. So we wanted to create this production library where anyone who wants to create anything can go and look up any artisan and check them out. This is also a good thing for the artisans, putting them on the map. We collaborated with The Ready Hand because they had already started the work on cataloging, so we decided to work together.

JG: You also see the impact it had on artisans. For example, we went back to one artisan and asked them to reproduce X amount of this object, and they were amazed. They’re used to making a one-off table collectible. We also hear a lot of appreciation from them, expressing their thanks for referring them to designers. It’s a new perspective they didn’t have before; this whole ‘us’ and ‘collaborative’ approach to craftsmanship.

image © designboom

AG: Most Lebanese artisans we work with are part of the older generation, so they don’t really engage in social media promotions and exposures. When we post a picture of them at work, they turn skeptical and ask us why we’re doing that. We tell them to wait and see the results. In my case, I went back to visit one of the artisans we featured on our socials two weeks after, and he told me that someone saw his pictures and what he does on the ‘internet’ (laughs) and reached out to him; he was happily surprised. That’s why keeping a good relationship with artisans is crucial for designers. They’re creating your work, so you need to maintain that back-and-forth interaction or hit a wall. They’re the ones with all the production experience. We, on the other hand, offer the technological expertise with our CAD drawings, so there needs to be a middle ground and an good collaborative dynamic to make things work.

TA: When you work with artisans, you also start developing techniques and ways of working. This is why some designers don’t like to share their artisans with others because they’ve worked so long with them, developing new techniques and fostering a unique relationship with them. They don’t want others to come and take advantage of that. It’s like this secret ingredient you add to each product, but I’m happy that competitive spirit is dialing down.

‘Nectar’ incense holder by Paola Sakr | image by Exil Collective

DB: How do you envision your collective growing, and what are your future projects?

JG: For us, Exil Collective is very flexible in the sense that we want to expand in different areas. One of our dreams and goals is to have our own manufacturing capabilities and workshop spaces with artisans and designers and even hold workshop programs with other countries.

TA: Youssef and Antoine did a workshop in Armenia with eight students for three weeks, and the idea was to import the same criteria and specification sheet that we created for Exil into Armenia — see what material is available, what production means are available, and develop products from there. It went very well. A school from France also reached out to us; they want to get their students here to learn. This is how we wanted to grow, very organically. We want artisans to travel as well and learn new techniques that we may not have here and maybe also bring foreign artisans to teach them. Again, it’s about instilling and expanding that collaborative spirit and environment.

left to right: Youssef Bassil, Omar Bassil, Tatiana Akl, Joseph Geagea, Antoine Guekjian | image by Exil Collective

JG: We also want the artisans from the previous generation to be able to pass down their savoir-faire to younger designers. Lebanon is very lucky to have this artisanship going on for years and years, and we want it to continue growing with every new generation. We want students to feel like they can create without these constraints (as in lack of access to savoir-faire). One of the nice things about our exhibition in Dubai was that we displayed all of our designs on one table, at the same level — joining the ten established designers’ creations with the ones from our 15 up-coming designers. For once, people were looking at the products without distinguishing them by their creators; they genuinely appreciated the objects for what they were. And this is a testament to our vision: If you offer the right space and ecosystem, everyone can do amazing work because there is talent and knowledge in the region. There’s no doubt about that.

TA: We also want to develop our own products and furniture line and discover new designers. We want to be the middle ground between the IKEA and BHV fast designs and the more expensive ones so that people can afford nicely designed products.

flat plack, intuitive, and simple design | image by Exil Collective

studio visits (112)

PRODUCT LIBRARY

a diverse digital database that acts as a valuable guide in gaining insight and information about a product directly from the manufacturer, and serves as a rich reference point in developing a project or scheme.