on june 19, 2018, la triennale di milano presents a public symposium to introduce some of the central topics in the upcoming XXII triennale di milano titled ‘broken nature: design takes on human survival’, on from march 1st to september 1st, 2019. an international roster of designers, architects, scientists, curators, and thinkers from a range of backgrounds are offering a dynamic exchange of opinions through presentations, panel conversations, video contributions, and lectures. speakers will strive to answer questions such as: how can designers, scientists, politicians, and scholars support all citizens in taking constructive action on urgent issues related to natural and social environments? what have they done in the past, and what do they plan for the future? how can they help move people’s focus beyond individual and immediate concerns, and instead amplify personal and discrete initiatives into nuanced collective, systemic, and long-term attitudes?

ahead of the symposium, designboom sat down with paola antonelli, curator of the XXII triennale di milano, to learn more about the central themes of ‘broken nature’, the concept of restorative design, and how public programs can render the curatorial process more participatory.

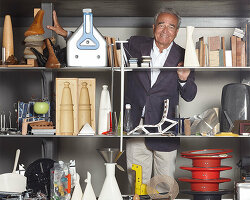

portrait of paola antonelli

designboom (DB): can you talk a bit about the relationship between this symposium and the upcoming XXII triennale?

paola antonelli (PA): the triennale will open on march 1st, 2019 but I tend to organize programs beforehand because they help me think, and help create a dialogue with the audience. this symposium will be followed by two more, one in new york in november and another one at the opening of the triennale in march. we have already started an online platform, brokenature.org, where we hope to document the entire curatorial process. we have published already posts that show the breadth of the subject, ranging from reindeer husbandry, to indian root bridges, to visualization and data humanism — and this is only the beginning. we will include all of the projects we are looking at for the exhibition, as well as the considerations being made about the kind of design we want. we want to make sure that it’s similar to a triennale of the past, having to do with contemporary issues not only about architecture and design, but also about the whole world. this triennale will not be a show to visit for the spectacle, but rather an opportunity to use this amazing building, to inspire citizens to really think of what they can do in their real life to have a sense of purpose, and to mend their relationship with nature.

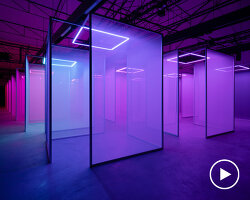

posts collected on brokenature.org offer insight into the kinds of projects featured as part of the exhibition

pictured here, living root bridge ecosystems of india by sanjeev shankar

DB: will there be a sense of participation as part of the triennale, beyond just visiting the exhibition?

PA: we definitely want that. there was recently a very interactive exhibition here at the triennale — ‘999 questions about contemporary living’. I’m not sure that we’ll be able to be as interactive, but we’ll try to be! in terms of the international participations, we don’t know what they will bring and what they will do, yet, but i have a feeling that many of them will have an interactive component, because that’s what we have seen in many biennials and triennials around the world in past years. that’s what I’m hoping will happen — I’m hoping they will be naturally interactive.

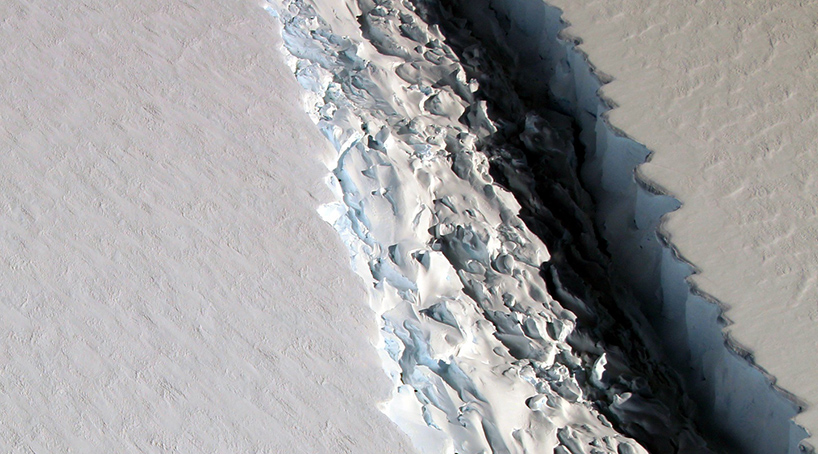

view of a massive rift in the antarctic peninsula’s larsen C ice shelf, 2016 | image courtesy NASA/john sonntag

from reparations by design by paola antonelli and ala tannir

DB: what do you hope visitors will take away from the exhibition?

PA: our triennale has three big goals, and they all are about people, about citizens. the first goal is that we want people to leave the building already having a sense of what they can do. not everything in the exhibition is going to be abstract or speculative. the second goal is to make people realize that they are part of a complex system. to give you an example: five years ago, a building collapsed in dhaka, in bangladesh — the infamous rana plaza tragedy — and killed 1,134 people. everyone was outraged by the working conditions of the people in the garment industry, and many reacted by vowing not to buy any more clothes made in bangladesh. the problem with this strategy is if you stop buying clothes, the workers have no income or means. this second goal is about knowing that there is no right, wrong, black, white, or completely absolute decision to make. every decision has a multi-faceted impact. every time — even in our everyday life — we have to think of many different consequences. the third goal is that we would love people to start thinking about the world in the long term- to think not just about our children and our children’s children, but farther away, in the future. that’s really an ambition.

a herd of reindeer roaming in the forest

from lapland reindeer by kristina parsons

DB: how did the theme of ‘broken nature’ first come about?

PA: ‘broken nature’ is a theme that was born in 2013, when I made the first proposal to MoMa. at that time, it was not the right moment for MoMa to pursue it, but we were all interested in the topic. a museum like MoMa has many priorities and exhibitions, so when this chance at the triennale came, it was a good opportunity. especially because parts of the xxii triennale — particularly the commissions — will travel to MoMa, to a special gallery for contemporary design. MoMa is currently undergoing an expansion, and afterwards, slowly, some of the objects will come to the museum.

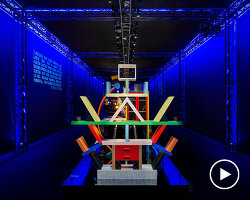

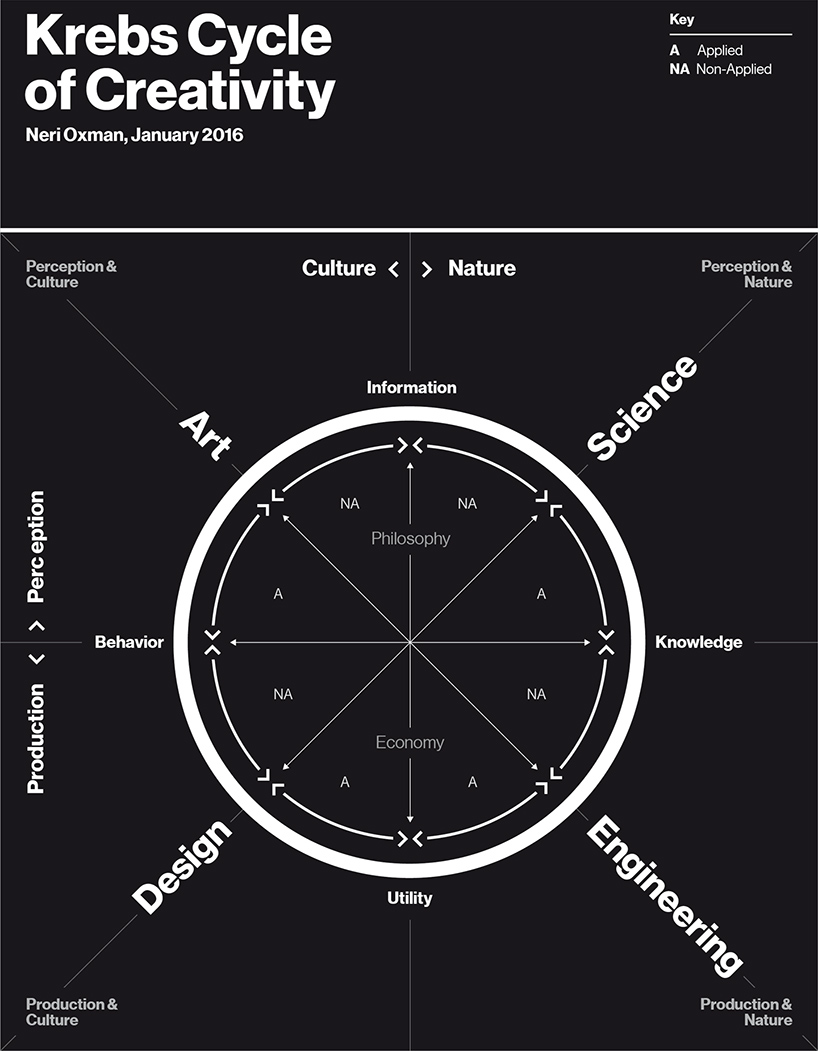

neri oxman, krebs cycle of creativity, 2016, courtesy the mediated matter group

from age of entanglement by neri oxman

PA (continued):

the idea of ‘broken nature’ materialized in 2013 for many different reasons. in my career, I have always been very attentive to science. this year is the 10th anniversary of an exhibition I curated called ‘design and the elastic mind,’ which focused on design and science. around that time, I had noticed how frequently scientists were talking about the sixth extinction, consilience, and the need to have more have more biodiversity — especially scientists like e.o. wilson, who are so important to me. they were pointing at the need to rebalance our connection with nature, not from a new-age viewpoint, but rather from a very scientific viewpoint. at that time, I started thinking about the threads that connect us to nature as human beings. nature does not mean only plants, animals, and oceans, it means other human beings and bacteria as well. I started thinking about how many of these threads have been severed in history, especially in the 20th century, while some have been strengthened. one might argue that civil rights for instance were strengthened, but others have been dangerously severed. I started thinking about how we could use design and architecture both as tools to replenish these ties, and also as ways to sensitize citizens about them. on the occasion of this triennale, we started thinking — I say ‘we’ because I work alongside a great curatorial team — about the idea of ‘restorative design’. restaurants were born in france in the 18th century as places where people would go to eat healthy, restorative food. afterwards, they became pleasant, convivial places where someone could go to find delicious food. maybe restorative design can be the same!

curators all over the world have done countless exhibitions about speculation, or speculative futures. I would like this exhibition to be a little closer to earth. there will be some speculative projects, but many of them will be real. there will be commissions, loans in the exhibition, as well as international participants. nearly the entire triennale building will be devoted to this project for 6 months.

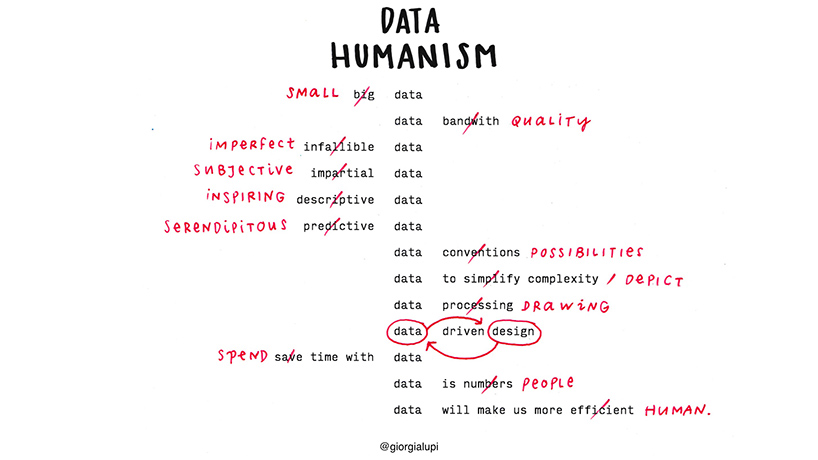

graphic from data humanism, the revolution will be visualized. by giorgia lupi

DB: can you give an example of restorative design?

PA: one example that I can give, because it’s already confirmed, is from formafantasma. there are so many exhibitions right now that deal with nature, that have asked designers for new projects. we want this triennale to be different. formafantasma started a beautiful project in melbourne at the ngv triennial, so we asked them not to start something new, but to continue this great project. by enabling them to continue their research, we help designers become more credible, treating them more like scientists than like artists, and allowing them to continue something that is very valuable. moreover, we create a new type of exhibition that is part of a system rather than existing on its own. formafantasma’s project ‘ore streams’ is important also because it’s very concrete. it shows how electronic waste can be used and also introduces an important concept that I think would be wonderful for citizens: that waste is not waste but rather a new material. this is an example of restorative design. it’s not about fixing a table, it’s about thinking about things in a different way.

looking toward ground zero at the trinity nuclear test site, 2017, photo by gabriel ruiz-larrea

from green glass rocks and red clouds: postnuclear media objects of the anthropocene by gabriel ruiz-larrea

DB: how far do you think design can go in the changing of civilization?

PA: I believe that no discipline can do it on its own — not science, not technology, not politics. it all has to come together. design on its own — no. but design can help citizens understand and put pressure on politicians, and it can help scientists experiment without the load of peer scrutiny. I always argue that there would be no innovation without design — good or bad — it doesn’t always have to be good. every technological innovation needs designers to translate it to people. there are some objects and products that remain outside of the consumers’ market, for instance machinery and lab appliances in factories, that don’t need such an interface as badly, although you could argue that they should get one, too. design is not only about embellishment, but always about clarity and safety. truly, design is the enzyme, it has to be part of a process, not by itself. it is not one discipline, but a whole frame of mind that needs to change.

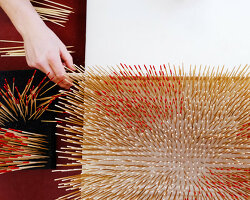

for ‘ore streams’, formafantasma uses electronic waste to create office furniture concepts

read more about the project on designboom here

DB: are these ideas also reflected in the symposium?

PA: I organize a lot of public programs, and their success is really about alchemy and chemistry. we invite people that seem to come from many diverse backgrounds, and then realize they are all talking about the same thing — that’s what I love. I hope that from this symposium, one of the aspects that will come out is the urgency of this topic. amongst the speakers, formafantasma are going to contribute a video. I don’t think many people in italy know maholo uchida or adam bly, both who are quite fantastic and come from very different backgrounds. maholo is the chief curator of miraikan, the national museum of emerging science and innovation, in tokyo. I’ve known her for a long time and she has a beautiful theory about how the japanese interact with humanoid robots. it’s a theory that connects to shintoism and is really fascinating. adam is an old friend and precious collaborator. we worked together on ‘design and the elastic mind’ — we go that far back! he’s going to talk about complex systems. he has a purpose-driven ai startup, and was at spotify for a while. it’s going to be really interesting to see how they interact with all of the others. what all of these people have in common is a connection to our environment. this is what really threads them all together.

the event will be live-streamed on la triennale di milano’s facebook page and youtube channel

DB: are you planing on using the outcome of this symposium to inform the exhibition?

PA: big time. a symposium like this and an online platform help me do my work — otherwise I can spend too long in the planning stage. I’m also hoping that it will help some of the speakers in writing their essays for the catalog. I’ll record everything, transcribe it, and then if the speakers want, we can use it. the catalog is not going to be about the symposium, but I plan to use it as help for all of us. you always have to be practical!

DESIGN INTERVIEWS (44)

TRIENNALE DESIGN MUSEUM (20)

PRODUCT LIBRARY

a diverse digital database that acts as a valuable guide in gaining insight and information about a product directly from the manufacturer, and serves as a rich reference point in developing a project or scheme.