a liveable future for the deceased by A deCocqueau from belgium

designer's own words:

Introduction

Japan met with a thorough economic boost in the aftermath of the war. This economic growth led to a rapid urbanization, as this was the perfect moment to enjoy the benefits of agglomeration. Industrialization was mainly concentrated in the core areas, the leading economic kernels in Japan. This proved a sizable improvement for the financial situation of Japan, positioning it 2nd on the list of largest GNP’s in the world. However, there were disadvantages too. The gap in living standard between the urban metropolises and the rural areas grew like never before. There was an immediate overpopulation, severe traffic congestions; air and water pollution marred the urban areas. Urbanization-induced migration accelerated the population rise in the major Japanese cities by almost 50 percent. Most of these people live on no more than 2% of the total area of Japan, testifying to the explosive process and the density of the urbanization.

Objectively, Japan’s population more than doubled between 1920 and 2011 to the more than 126 million inhabitants it has today. To top this, Japan has one of the ‘greyest’ populations world-wide. In 2005 a census was taken, showing 20.2% of the inhabitants to be of age 65 or over, and the expectations indicate that a portion of more than 40% will be older than 65 by the year 2055. These rises are due to the combination of one of the highest life-expectancies and one of the lowest fertility rates in the world. In 2011, men were predicted to live to the age of 78.96 years and women to reach 85.72 years, while the fertility rate dropped to 1.21 children born per woman.

Drastic urbanization and the exceptional increase in the number of elderly fused into an extreme burden on the cities. One aspect I will focus on here is a consequence of the densification of the population. As many more people live on an ever smaller amount of space, more people pass away there as well. Ever less space is available, while comparatively more deceased needed to secure an ultimate resting place. This led to a critical situation, raising many questions regarding how to correctly treat the dead. Besides that, the concentric development of cities and a capitalistic ideology resulted in over-priced, standardized mortuary facilities that continued to be pushed ever further away from cities, thus separating them in distance from the people who need their proximity the most. Passing away didn’t just become a burden for cities, but was now also a practical inconvenience for descendants and mourners. A dear one dying now implied a sizeable financial investment from the ones left behind, as well as a huge consumption of their time. Not everybody could afford this financial bloodletting, creating a degree of social pressure. This problematic situation has only worsened since the beginning of the 20th century, resulting in much dissatisfaction and criticism. Today, it is time to generate fundamental changes, changes that offer a solution for the future and bring back dignity to what for many is a moment of utmost intimacy and serenity.

This research, ‘A livable future for the deceased’, encompasses an urban/architectural proposal that attempts to offer a viable solution for the problem of dignified burial. I would also like to try and form the outline of a solution for the environmental, economic and social drawbacks that cities and mourners have encountered in as far as they are side-effects of urbanization and industrialization. It will present itself as a system, which could be implemented on any existing city, rather than as a defined approach to a specific one.

The tree burial

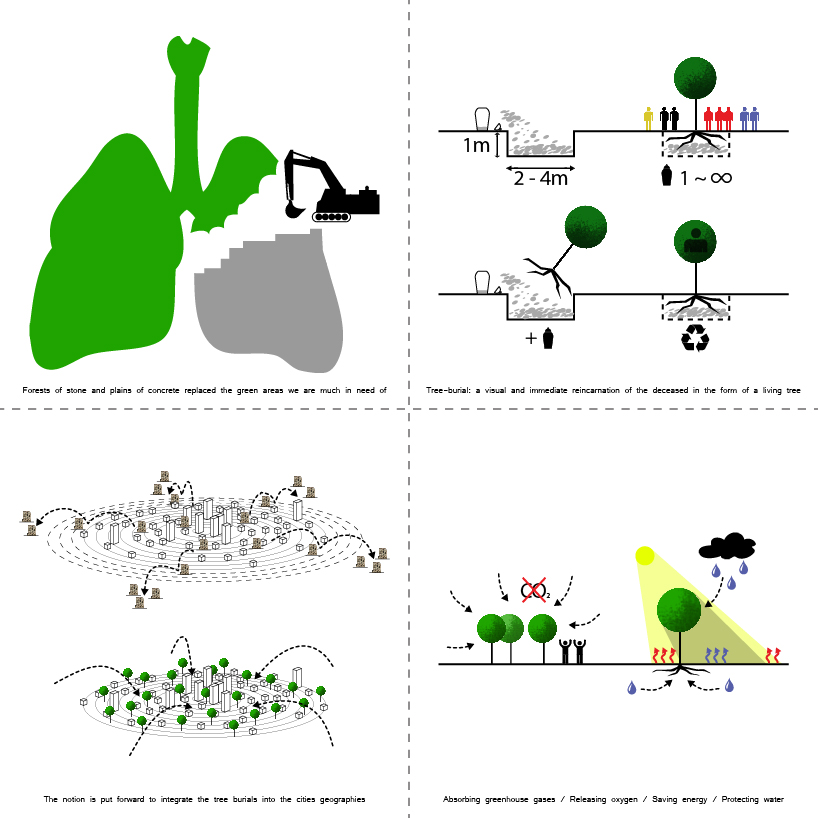

Sad or inevitable, the purity of nature has been deteriorated by the necessities of urbanization and the prowess of industrialization. Forests of stone and plains of concrete replaced the green areas we are much in need of; in agglomerations all over the world they have become notably scarce. This is markedly true of Japan, as Japan had no option but to urbanize very densely. Therefore, treating the dead following the ideological cycle of returning to nature is strongly recommended, if not outright logical. The tree burial not only diminishes the devouring of green space as a consequence of the mortuary facilities, but actually reverses it, creating new green.

The tree burial offers a flexible, straightforward and reliable practice to dispose of physical remains. It also possesses a poetic beauty: the visual and immediate reincarnation of the deceased in the form of a living tree. He revives, going through an evolution; from a small tree up to a full-grown, healthy one, much in the way we watch human children’s growth. The tree burial also encompasses the advantage of a wholly bio-degradable procedure, leaving no traces if abandoned. Besides that, the tree burial ceremonies are felt to be much more personal and are claimed to hold withered emotional references. Even though sometimes multiple families assist, their focus is on providing an intimate memorial directed at the individuality of the departed. The bereaved feel more involved, since their physical movement is instrumental in the burial: instead of having everything done by expensive, unknown undertakers, they themselves now carry the ashes from a mundane, residential space, to a natural but applied surrounding. They themselves dig out the hole and spread out the ashes in it.

The tree burial also highlights his qualities on the space efficiency. A tree burial is possible for a single person, but there is no limit to the number of people allowable in one opening in the ground. On a surface of approximately 12-15m², the remains of 1 to 50 or more people could be interred. After the ashes are spread, a young tree or shrub is planted. The choice of tree or shrub is free, as long as it suits the ecosystem of the location. The amount of people present at the ceremony will vary depending whether it is a single-family or multiple-family tree burial. Different families, friends, even strangers may be united. At present, this leads to no debate, as the traditionally recognized forms of relations have been fundamentally expanded. The possibility also exists to add new ashes to the tree after it is planted. This is done by picking up the tree, spreading the new ashes and replacing the same tree in the same position.

Implementing tree burials within cities

As we know, mortuary facilities in cities have been expanding in outward concentric movement. This led to the problems discussed earlier, making them a menace for the environment. As it is today, tree burial offers a way out of some of these difficulties, but the fact remains that the site of interment is often located far away from the city centers, inhibiting the mourners to visit. In the present proposal, the notion is put forward to integrate the tree burials into the cities geographies. The environmental threat of graveyards devouring the countryside could be opposed by the beneficial practices of the tree burial; this may well change the light in which the interment practice is seen. It’s certainly a step towards returning to nature what had once belonged to it. On the long term a much more attractive future is on offer here. An increasing number of deceased will not automatically result in more walled-in stone fields, but rather into green, accessible area, changing the perception of it in the process. Attempting to integrate the sites in the hearts of the cities will return the deceased within the proximity of their descendants. Underlying this development is the idea of maintaining contact with the dead by simply having them coexist with the living.

What trees can do for cities

- Absorbing greenhouse gases and releasing oxygen

- Saving energy (thus reducing energy cost) by shading in summer and take the edges off the cold winter winds.

- Trees reduce topsoil erosion by breaking the fall of rainwater with their leaves Reinforce the ground with their root structure. The roots also help to remove nutrients from the soil that are harmful to water ecology and quality, slow down water run-off, and ensure that our groundwater supplies are constantly replenished.

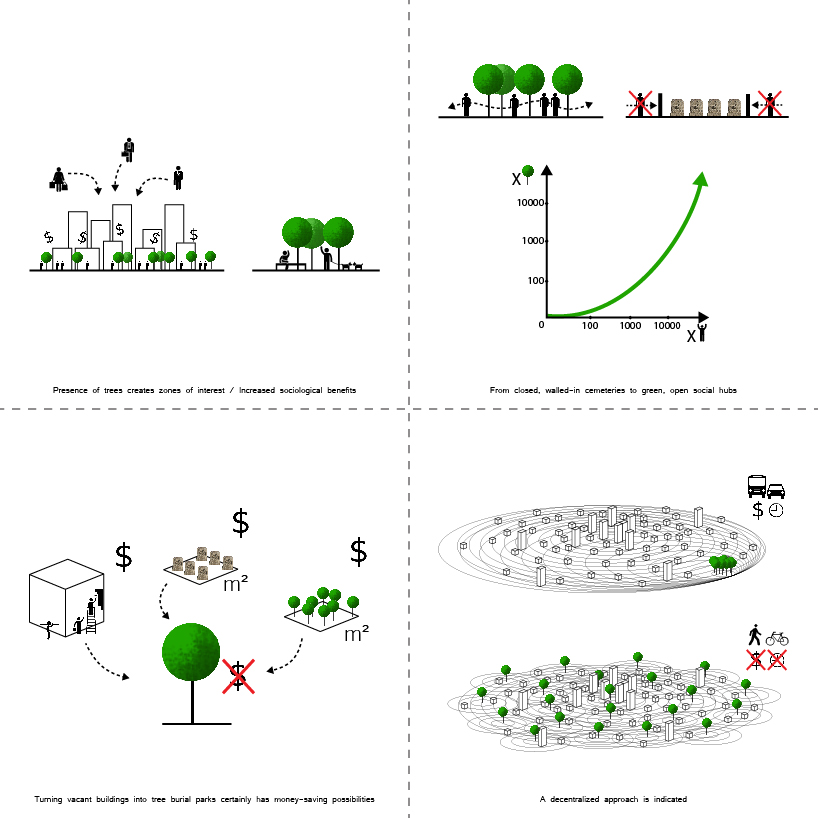

- Urban forests make locations generally more attractive and they introduce calm, reflection and wellbeing. Their presence creates zones of interest for business and it encourages tourism.

- Trees provide one with a reason to go outside. Residents in wooded areas have been known to entertain significantly better relations with and stronger ties to their neighbors. Studies have further indicated that hospital patients with a window view on trees recover faster and with fewer complications than similar patients without these views.

But trees possess even more advantages. Implemented as indicated here, they would also help change the perception of the deceased and of the cemeteries, since today the space they occupy is regarded as uselessly blocking development. Grossly put, creating green cemeteries would equate to turning death into trees. The commemorated would, although dead, recover a role in daily life. People will have cause to be proud of their deceased, as their reincarnation can now be physically viewed and is established to have positive use. Having a living tree instead of a dead stone is psychologically an advantage in the process of assimilating the death of the loved one: you can now see his/ her marker grow and change over time, rejuvenating again and again with the passing years, instead of facing an abrupt end which rather suggests the nullity of human life and the irrevocability of its end.

The tree burials offer a solution to solve all drawbacks encountered so far. Of course, the practice of tree burial will only effectively exhibit all its positive features when implemented on a city-scale; this is: when a certain number of trees has been planted. With the rise of this number, its effect will broaden and deepen. The wider the method of tree burial is implemented socially, promoted by the cities and the states and supported by its citizens, the sooner a more attractive, healthier and luscious city will appear. As any other change requiring an adaptation of mentality – however slight - this shift will not happen overnight, but it is possible to foresee a gradual process spread over some time, set off perhaps by the first results.

Strategy to implement tree-burial in cities

Carefully thought-out urban strategies will be required to implement the tree burial successfully within city hearts. The goal on the long term would be to replace the stone graves by tree graves in order to undo the urban, environmental and social suffocation that cities are facing today: they need to provide mortuary facilities on a walkable (or, say, a bike-ride) distance from people’s homes. To create a wide acceptance of the use of the tree burial as a cultural norm, the best results will obviously be achieved without factually imposing the practice on anyone, but by frankly implementing it and letting the advantages show themselves. If forced upon a population, apprehension will inevitably arise; needed here is a smooth, linear and gradual process. First of all, the tree burial habit will need to be recognized and promoted by the cities: today, it is still quite unknown. As it is still the people involved who choose the funeral practice, it is important to direct public attention. The tree burial’s obvious potential, from which cities and their inhabitants alike can benefit, needs to be proposed to them as an option.

Like for any other mortuary procedure – even if it be less in case of tree-burial - some space will always be required. As mentioned before, this is a very real problem in Japanese cities, as many of them are saturated to the rim, having not one single square meter left free. Of course, we could stray even further from the city centers, but this would only worsen the distance-problem. It nonetheless seems possible to find this space at the very heart of the cities. To do so, I will make use of a demographical characteristic that has already started, and is expected to grow significantly in Japan, namely: the shrinking of segments of the Japanese population.

The Shrinkage of the Japanese population

Due to a severe drop in fertility rate from the mid-20th century to now, an out-of-balance society was established. Japan has both one of the highest numbers of elderly in the world, and one of the lowest numbers of youth.

All of this amounts to a reduction from 126 million to an expected 92 million by 2050. This denotes a shrinkage of about 27% of the Japanese population, considering a timespan of only 40 years!

This altogether severe reduction will have many implications for the economic power and for the urban tissue of Japan. Cities are going to be faced with an overload of vacant residences and of public facilities, as they were foreseen to accommodate 126 million inhabitants. Vacancy on this scale induces problems of underutilization; it hampers the efficiency of urban flow and petty crime ensues. Instead of leaving these abandoned buildings to become ruins, or force the city to waste money on maintaining them, these leftover buildings could be transformed into tree burial parks. As the amount of abandoned buildings must logically go up proportionally to the rise of shrinkage-caused deaths, free space will be available for these new deceased to be buried in dignified fashion at not too great a distance. The system so created is balanced and complementary; it allows for all the trump-cards of tree burial to be played.

A major drawback of the effects of shrinkage is our impossibility to quantify it. How many vacant buildings it will actually create is hard to estimate. Furthermore, of course, not all spaces that will vacate are suitable for transformation. Japan opted more and more for a vertical way of life; so many multiple-story buildings have been built in Japan. Progressively, these filled up to finally house a fair share of its population. There, demises do not liberate, directly or indirectly, space reusable as tree burial area. Basically, only single houses or fully abandoned multiple-story buildings are potentially suited. In addition, some of these single-houses may not become vacant, due to the ongoing urbanization of Japan, or due to a deceased’s relative taking over the property and preferring it to his earlier habitat; as such it only results in a change of proprietor.

However, knowing that statistically more and more people in Japan live alone, are unwed and with no descendants, many of them will have no one they could possibly pass their property on to after death. Even if they would have an option to do so, it would probably still stay disused, as life expectancies continue to rise. Mathematically, this means that, at the moment a person dies, their descendants will be older too, and probably already own a property themselves. So, taking all of this in consideration, the reduction of the population will still result in a sizable amount of space open for transformation into tree burial areas.

Advantages of using the vacant plots

For the cities, turning vacant buildings into tree burial parks certainly has money-saving possibilities. It may even create structural profit. Firstly, no tax-money will be spent on the maintenance of a disused building. Secondly, the need to buy up land outside city limits (imperative in case of concentric enlargement) will be reduced or, best case scenario, will evaporate. Nor will city authorities need to purchase allotted land to create the much needed new ‘lung’-spaces, as the tree burial satisfies both needs, whilst only consuming half of the space. Thirdly, the tree burial area will increase the estate-value of the buildings around it (that now have a park near them), creating more income through taxation. Fourthly, as the trees will notably improve air-quality, investment needed to fight pollution is reduced, as well as the medical costs.

When changing to a tree burial cemetery, a more efficient land use can be obtained. On the same surface, it will become possible to inter more ashes, decreasing the price of a burial plot. Certainly a temptation to change towards tree-graves will make itself felt, because not only does the (sometimes unreasonably hefty) plot price disappear, it also reduces the maintenance cost of the family-grave. (These last costs could for instance be absorbed by the government as part of an encouragement in opting for a tree burial).

But besides these financial-related incentives (we’re only too aware of it: depending from one city to another), there exist even more reasons to tempt one to shift from a stone grave to a tree grave.

So, let’s summarize the different steps. With the shrinkage of the population, vacancies must arise. The city could buy up these buildings, or could claim them if there is no one in line to inherit them. These could then be physically transformed into tree burial parks. After doing so with the first few buildings, the tree burial will show its natural advantages and as such, it is not unreasonable to hope that it may become an accepted practice. People will start to consider it for themselves: a mentality-shift could be accomplished, especially because an exchange of a stone area for a wooded one will generally be seen as an improvement. The painful and stubborn issues encountered in dealing with the dead may be resolved, and hope is permitted to tackle the expected urban knots that will result from to the shrinkage of the population.

Decentralized < > Centralized

For the implementation of tree burial within the cities, I am convinced that a decentralized approach is indicated. It is better to have many small areas spread out than creating a few big ones, close to the lucky few. The former, certainly, is how it used to be in ancient times: many temples were spread over a city, and many of them had cemeteries. In this way, proximity was assured and commemoration could be carried out with evidence and ease. But urbanization pushed the cemeteries out. The outlying burial grounds became bigger and more concentrated. As a consequence, the descendants lost touch with the deceased.

First of all, the strategy of converting the vacant spaces into the tree burial grounds, results in a variety of spaces spread all over the territory, thus by definition being decentralized. Besides that, the trees are the embodiment of one’s loved-ones and would be easily accessible at any time the bereaved feels an impulse to visit it. Time and expenses for such a visit would be drastically reduced, making it more spontaneous and better suited to the nature of remembrance than it is today. It is certainly possible to envision these tree burial cemeteries as social hubs, becoming at times very lively, with children playing or people meeting each other there.

For maximum effect, this decentralization should not only be implemented on the cemeteries. In the present outline, one imagines readily all the new mortuary facilities to also be decentralized and to be linked. (Today, funeral halls, where the ceremony is held, are decentralized, but graveyards and crematories are mostly centralized). Thus, while in function these facilities are narrowly related, experience proves that physically, they are often not well connected, demanding time-consuming, inefficient movement. It is a tall order to have the mortuary facilities scattered as well, but proximity of all the participants (funeral hall, crematory and green cemetery) would make for the much desired fluency and for flexible co-operation, certainly if all were within a perimeter of x-kilometers. This perimeter of proximity must forcibly depend on the density of the area and upon its population; a requirement for this is that these facilities also will downsize. But the gain would be a steadfast availability (to the point of being independent of the whims of traffic) and a better guarded intimacy.

Public < > Private

Present day funeral facilities are in private hands, so they mean business. Sometimes to the point of lacking respect for individuality. People’s feelings of mourning and loss, their ethical morality and their rooted convictions were left aside, leading to a standardization of funeral process. Often, the facilities housing the process looks much like a factory, built as cheaply as possible, harboring no soul or exuding no accommodating atmosphere.

Making all mortuary facilities publically owned would have many advantages. The cynics would have it that government cares only for funding, but amongst their responsibilities are social security, public health and the upholding of a degree of wellbeing, generally termed ‘standard of living’. The subject treated in the present work falls under each of these headers; a government presenting its citizens with a fluent and dignified mortuary service could certainly put this forward as an achievement.

The fact that governments would own the mortuary facilities could fundamentally reduce its prices and reduce the time, efforts and paper work needed to manage it all. Together with the proposal to join the mortuary facilities in close proximity of one another, arranging one’s funeral, cremation and burial must become feasible, even for a bereaved still coping with loss and possibly still disorientated by it.

Secondly, making the mortuary facilities government owned could, given the political will to do so, also result in better and more beautiful facilities. Constructions are the major building blocks of the cities’ image; a veritable incentive for the Councils to improve upon the quality of their architecture. Alternatively, this could be improved by writing out architectural competitions or by approaching signature architects. Valor in the building art and uniqueness reflect on people’s behavior and feelings. Something made with respect and empathy for a class of users, generates recognition and satisfaction from them. A qualitative building will also make the event more remarkable and memorable. It is thus of crucial matter that the construction of the facilities should not be simply consumed by the interests of short-term investment and current fashion. They must conjure up deeper meaning and interest for its visitors. They should become places where beauty has the power to redeem man from his limitations. Such is the modest ambition of the present proposal. Changing the obsolete and frankly ugly funeral halls and crematories – making death on the outside visible and thus unattractive – into good-looking, appropriate buildings, will motivate one to be in contact with the dead more frequently and in more depth. Architectural valor and the evident integration with nature in close contact with the surroundings as well, are intended to make passing away the very common event that is, recognized and embraced by everyone, without in any way decreasing or modifying its significance. The idea is that, without naiveté, the living and the dead would coexist without obstructing each other.

Conclusion

Matters death-related are in a crisis, indicating a cry for thorough change. The idea brought forward and developed here is a change in social view of the subject, namely from an unknown, disturbing and negatively co-notated entity (inspiring fright, apprehension and indifference) to one well-acquainted, familiar and positively co-notated (inspiring rest, regeneration and fruit of thought). Today’s stone grave cemeteries, the businesslike funeral offices, the non-committal and often poorly designed crematories and the deserted temples do create a barrier between living and dead. No care has been taken of the representation of death, making its oblivion and neglect easy and general.

In the words of good Socrates, who led by example: “To fear death, my friends, is only to think ourselves wise, without being wise: for it is to think that we know what we do not know. For anything that men can tell, death may be the greatest good that can happen to them: but they fear it as if they knew quite well that it was the greatest of evils. And what is this but that shameful ignorance of thinking that we know what we do not know?” (470BC) Shameful, indeed. If anything this work has in the broader frame learnt me, it must surely be that our view upon death is in need of reappraisal. Yesterday’s view as well as its symbols (stone markers, giant requiem masses, the odor of disease; inaccessibility and forbidding) can no longer be upheld as actual. This is not to say death should be treated with less than due respect, without reflection and awe, or should be taken lightly in another manner. Death will always remind us of our own mortality.

However, it is within today’s esprit du temps to accept the bounds of what we know and not know with greater ease. Towards our children, we do not pretend any longer that we are wise to all secrets (for fear they might think our authority less than total): we know not and we tell them. It’s inevitable: we are human and there are frontiers to what we are aware of; with time, the child will understand and in turn say so to its children. It is to this inevitability – which holds in it acceptance – that this work hopes to contribute. About death, we know not – how much fear is then actually warranted? How long mourning, how deep grief? Is this what the deceased wanted from us? Is it not time for an all-out avowal: death is there, it is terrible, but on our planet there is nothing we can do about it, so, for the sake of dead and living alike: let’s accept it – no more, no less.

Tree-burial Perception change of cemeteries/ Strategy to implement

Perception change of cemeteries/ Strategy to implement Strategy to implement / Government-owned

Strategy to implement / Government-owned