KEEP UP WITH OUR DAILY AND WEEKLY NEWSLETTERS

PRODUCT LIBRARY

the two films highlight AI's ability to provide insights into global ecosystems, emphasizing its role in analysing data to predict and mitigate risks.

connections: +540

designboom is presenting the sound machines of love hultén at sónar festival in barcelona this june!

connections: 85

BMW releases the upgraded vision neue klasse X, with a series of new technologies and materials especially tailored for the upcoming electric smart car.

following the unveiling at frieze LA 2024, designboom took a closer look at how the color-changing BMW i5 flow NOSTOKANA was created.

connections: +640

closer view of the hood image © tina chou

closer view of the hood image © tina chou fashion design student matilda ceesay poses with models outfitted in the ‘njehringe’ pieces image © tina chou

fashion design student matilda ceesay poses with models outfitted in the ‘njehringe’ pieces image © tina chou in ‘look three’, the splits in the skirt recreate the look of traditional wrap skirts; while the soft, shaped bodice is intended as bridge between the structure of corsets and the loose cuts of african tops image © tina chou

in ‘look three’, the splits in the skirt recreate the look of traditional wrap skirts; while the soft, shaped bodice is intended as bridge between the structure of corsets and the loose cuts of african tops image © tina chou closer view of the ‘look three’ top image © tina chou

closer view of the ‘look three’ top image © tina chou the structured, corset-like shape of the skirt in ‘look five’ reflects ceesay’s question, ‘would west african natives who had no contact with westerners use the garments as they were intended? if they found a corset how would they know it was meant for the upper or lower body?’ image © tina chou

the structured, corset-like shape of the skirt in ‘look five’ reflects ceesay’s question, ‘would west african natives who had no contact with westerners use the garments as they were intended? if they found a corset how would they know it was meant for the upper or lower body?’ image © tina chou ‘look one’ investigates the long west african tradition and variety of the dying and weaving of fabrics image © tina chou

‘look one’ investigates the long west african tradition and variety of the dying and weaving of fabrics image © tina chou closer view of the ‘look one’ skirt during the cornell student spring fashion show 2012 image © tina chou

closer view of the ‘look one’ skirt during the cornell student spring fashion show 2012 image © tina chou ‘look four’, a 19th century-style corset with bloomer shorts and cape-like jacket image © tina chou

‘look four’, a 19th century-style corset with bloomer shorts and cape-like jacket image © tina chou the voluminous hem of the column dress emulates the way african women lift their skirts when performing chores image © tina chou

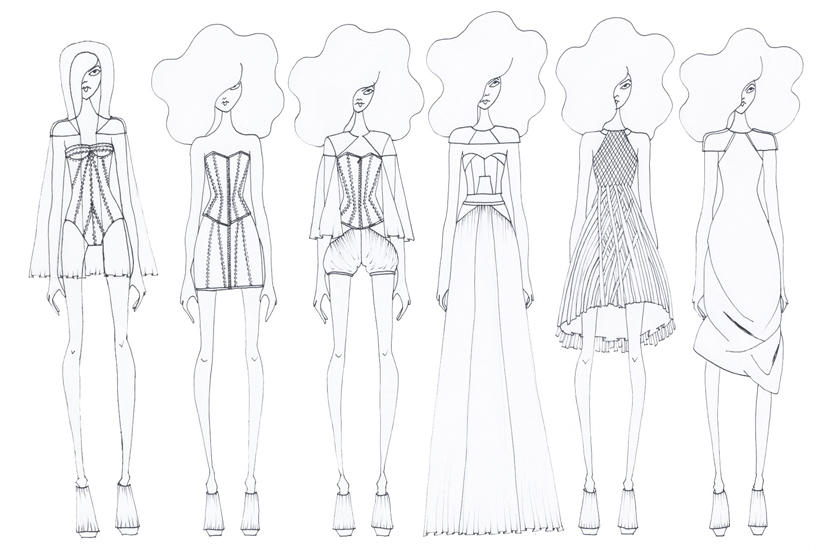

the voluminous hem of the column dress emulates the way african women lift their skirts when performing chores image © tina chou design sketches for the collection

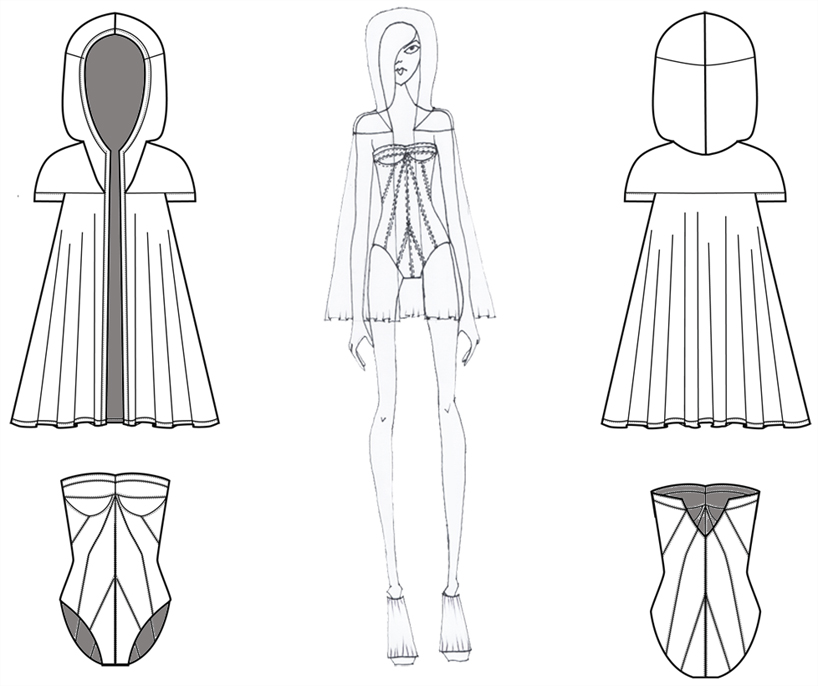

design sketches for the collection design concepts for the hooded, insect-repellant jacket

design concepts for the hooded, insect-repellant jacket during the cornell student spring fashion show 2012 photograph ©

during the cornell student spring fashion show 2012 photograph ©  the innovative hooded jacket on the runway during the show photograph © jason koski / cornell university photography

the innovative hooded jacket on the runway during the show photograph © jason koski / cornell university photography