KEEP UP WITH OUR DAILY AND WEEKLY NEWSLETTERS

PRODUCT LIBRARY

designboom is presenting the sound machines of love hultén at sónar festival in barcelona this june!

connections: 74

BMW releases the upgraded vision neue klasse X, with a series of new technologies and materials especially tailored for the upcoming electric smart car.

following the unveiling at frieze LA 2024, designboom took a closer look at how the color-changing BMW i5 flow NOSTOKANA was created.

connections: +630

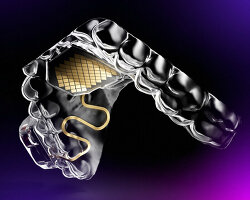

each unit draws inspiration from emergence, featuring a hexahedron-based structure that facilitates integration into larger systems.

connections: 96